The Wiener Library’s timely exhibition

‘The sympathy and freedom and liberty of England’

With wonderful timing, the Wiener Library opened its new exhibition, ‘A Bitter Road’, on the reception of Jewish refugees in the 1930s and 1940s, on Thursday 27 October, the day that the Calais ‘Jungle’ was dismantled and its residents dispersed. The coincidence didn’t escape the speakers at the exhibition’s launch, two of whom drew comparisons between the numbers of Jewish refugees taken in by the British government in the war years and the numbers of refugees who have been granted asylum since the Syrian conflict began. As Dan Stone (one of the speakers) said, ‘The number of children admitted through the Kindertransport scheme – although not their parents – was quite large: the same as the number of people in the Jungle.’ (The full transcript of his speech may be read here, on the University of East Anglia’s website.)

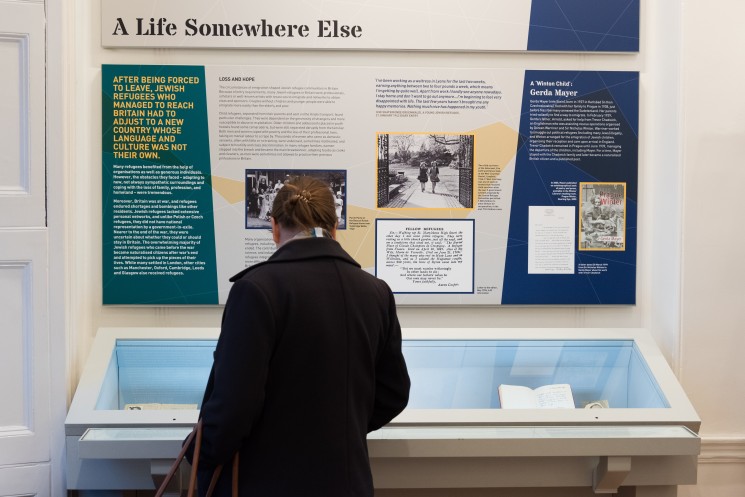

The third section of the exhibition, presenting the individual testimony of refugees. © Morag Macdonald

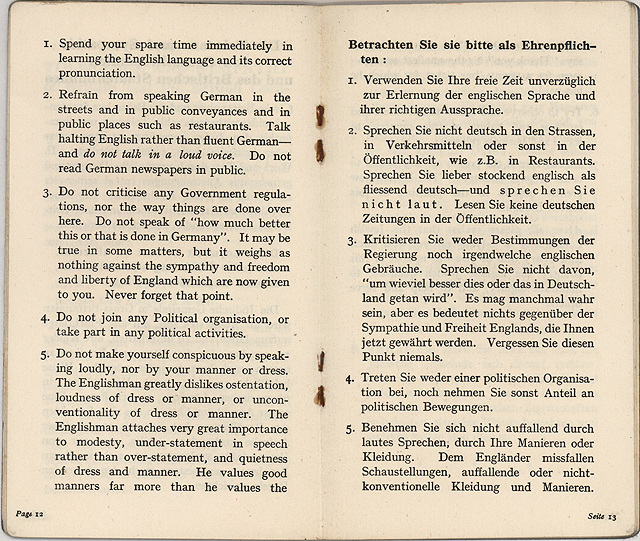

Much of the fascination of the exhibition, sub-titled ‘Britain and the Refugee Crisis of the 1930s and 1940s’, lies in the documentary evidence of ordinary people’s reactions to the experience of emigration and arrival in a new country. Booklets of advice on how to avoid drawing attention to yourself (‘Refrain from speaking German in the streets … the Englishman greatly dislikes ostentation’) make interesting reading, and raise the question of what those booklets would advise now; the complicated process of vetting and vouching for the refugees reveals a national paranoia that feels very contemporary. The suspicion Jewish refugees came under – being predominantly from Germany and therefore seen as potential enemy agents infiltrating Britain – inevitably brings to mind the suspicion currently directed at Syrian refugees and the fear that a refugee may be a terrorist in disguise.

Advice to refugees from Germany on how to behave in England . . . how much has changed? © Wiener Library

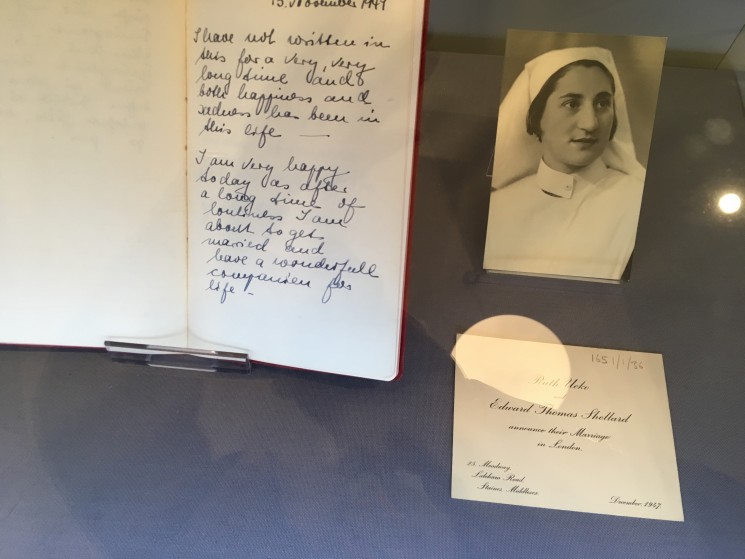

The bureaucratic formality of the reception process, which from this distance looks more obstructive than well-intentioned, contrasts with the more personal correspondence and diary entries presented elsewhere in the exhibition, one of which, written by Ruth Ucko, the first diary entry she wrote in English, announces her impending wedding as an emergence from a period of turmoil. A further section of the exhibition examines the media’s response to the refugee crisis, jumbling together headlines from the 30s/40s with today’s headlines in a way that shows how little has changed over the last 70 years.

A diary entry from Ruth Ucko, her first written in English.

At Thursday’s launch, Ben Barkow, director of the Wiener Library, introduced the three speakers, two of whom – Rabbi Harry Jacobi and Lord Alf Dubs – arrived in this country as refugees, from Holland in 1940 and from Czechoslovakia in 1938 respectively. Rabbi Jacobi spoke movingly about the circumstances of his escape on the last evening before the Dutch surrender to the Germans, a 14-year-old boy in a boat under fire from German bombers. He paid tribute to the woman who saved him, Gertuide Wijsmuller-Meijer, in a similar way to Alf Dubs’s recognition of the intervention of Sir Nicholas Winton (one of whose letters is part of the exhibition). Alf Dubs – the author of the Dubs’ Amendment, whereby unaccompanied refugees are to be offered safe refuge in this country – drew parallels with the current refugee crisis (the jury is still out, he claimed, on how his Amendment was being implemented), parallels that are a firm part of the exhibition, too, and on which Dan Stone, professor of modern history at Royal Holloway, University of London, focused in his talk:

Of the world’s 65 million refugees, some 10,000 tenaciously made their way to Calais, where they were stopped from proceeding to the UK and where, until a few days ago, they set up camp in the Jungle, a place which should never have been allowed to exist in one of the richest corners of the world (I’m talking of Europe as a whole, not Pas-de-Calais). Ten thousand is a six-hundred and fiftieth of 65 million, or 0.015%. These are not people who lack initiative or talent; they have determinedly made their way across dangerous terrain and ugly encounters with people smugglers and border guards in order to fulfil their dream of entering Britain. This country, with its ‘proud tradition of helping the oppressed’, has denied them entry and, with the exception of a few hundred children hurriedly allowed in as the French were sending in the bulldozers, refused even to allow children with relatives in the UK and, under Lord Dubs’s amendment, unaccompanied children, to enter, leaving them exposed to the dangers of the camp. Words such as ‘cynical’ come to mind.*

The exhibition is open until 17 February 2017. If you find yourself with half an hour to spare in the Russell Square area, I urge you to visit it. In fact, go and visit it anyway!

‘A Bitter Road: Britain and the Refugee Crisis of the 1930s and 1940s’ is open to the public between 10am and 5pm, Monday and Friday (10am–7.30pm on Tuesday), at the Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust & Genocide, 29 Russell Square, London, W WC1B 5DP. It runs until 17 February 2017.

*For more of Dan Stone’s speech, visit the University of East Anglia’s website.

Leave a Reply