The public’s engagement with migration debates

In a second blog for us, Assunta Nicolini, one of our regular volunteers, talks about how two of the seven moments in our current exhibition, No Turning Back, have caused visitors to raise questions about the complex relationship between race, migration and racism. Assunta is writing here in a private capacity.

A year and a half after the EU referendum, in which concerns about immigration played a major role, debates continue about what Britain’s future migration policy should look like.

In the lead-up to the release of a new Immigration White Paper framing a future British immigration system, the Home Affairs Committee published a report – Immigration Policy: Basis for Building Consensus – highlighting, among other things, current public attitudes to the issue of migration. It is encouraging to read that, despite the apparent polarisation of views about migration, the majority of the British public remains very open to engaging in a constructive, open debate on the subject.

Debate has been at the heart of all the Migration Museum Project’s exhibitions since ‘100 Images of Migration’, in which this photo, ‘Speaker’s Corner, Hyde Park, London, October 2009’, appeared. © Guy Corbishley

As a frequent and active volunteer at the Migration Museum, I have witnessed first-hand this willingness among visitors to our current exhibition, No Turning Back: Seven Migration Moments that Changed Britain, to engage constructively with the subject of migration. Regardless of visitors’ background in terms of race, gender, age or migration story, one attitude stands out: the desire to learn about the migration history of this country.

Guiding the public through the selected seven moments – spanning centuries – means also that visitors are prompted to constantly connect and compare past events with present realities, and to find out more about some of the complex factors that shape migration. By engaging with debates about the difference between economic migrants and refugees, for example, or the complex relation between racism, race and migration, visitors are able to find their own answers, share their thoughts and opinions, and respond to questions and contribute to conversations started by other visitors to the exhibition. It’s through this type of understanding that engagement becomes constructive.

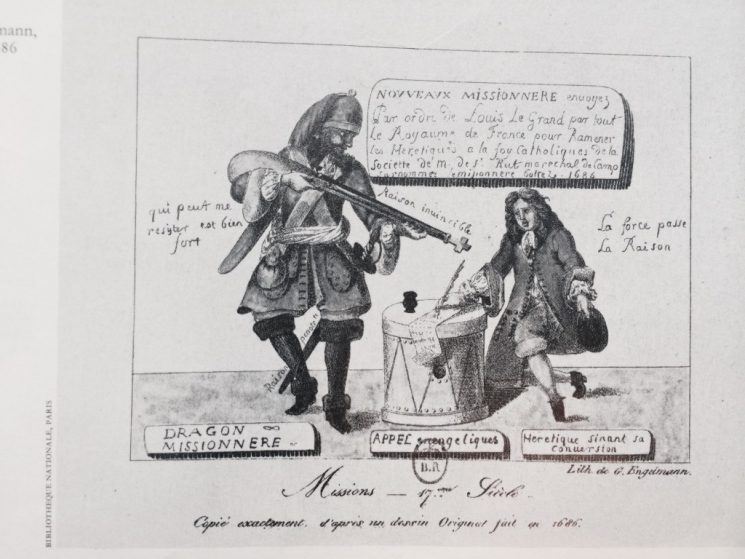

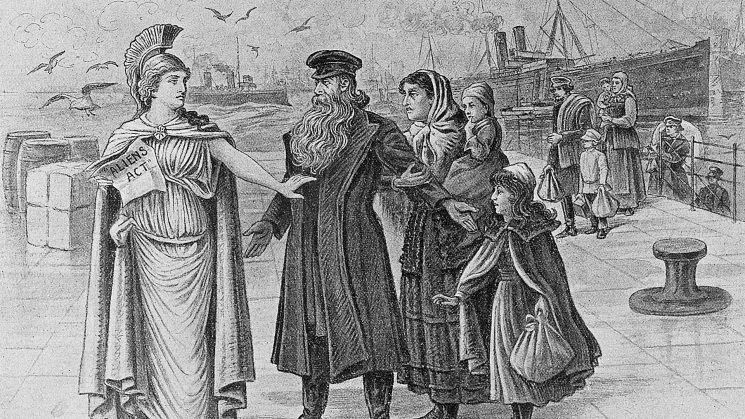

To use just one example, the current exhibition encourages visitors to think about how British migration, historically, has been framed by race – to familiarise themselves with one of the most important themes in contemporary migration studies, the racialisation of migration. At its core, racialisation focuses on the process behind ideas of race and how they adapt to specific contexts and times. It allows us to understand how race, which is socially constructed, is used to exclude, discriminate and subordinate those who are considered inferior by a certain dominant group. From the colonial era onwards, ‘dominant groups’ in Britain have continuously racialised and cast as outsiders ‘non-Brits’ on the basis of skin colour or religion. What this means is that, regardless of who ‘the Other’ is, whether non-white or non-Christian, ‘outsiders’ are placed in a condition of inferiority. This mechanism is the main driver of what we know as racism.

A visitor stands in front of Liz Gerard’s ‘The Chart of Shame’. © Migration Museum Project

The exhibition also explores the role of the media in shaping public opinion and reinforcing links between migration, race and religion. The Chart of Shame, a work by former journalist Liz Gerard that visitors can find in the 1905 ‘moment’ of the exhibition, displays all of the front page migration stories published in British national newspapers in 2016 in the form of a bar chart. Even if they are often not surprised at what they see, visitors are nevertheless visually shocked by the amount of attention given to migration; a closer look then reveals the often negative, racialised language used in so much of the coverage. You don’t need to be an expert in text analysis to count how many times derogatory terms referring to migrants and refugees are used, and to begin to think about how the use of this language feeds into and contributes to divisive narratives. The artwork, and the context in which it is presented, alongside a quote from Tony Gallagher, editor of the Sun, rejecting the suggestion that newspapers are responsible for creating divisive and hostile migration myths, gives visitors an opportunity to take in a large amount of data in one moment and to think critically about the role of the media in migration debates.

It is often at this moment in the exhibition that visitors display visible disappointment with, and even resentment towards, what they perceive to be a biased media, fuelling division in British society. Some ask, ‘What can we do? I’m not a racist, many people don’t even know their opinions on migration are racist . . . ’ – to these questions the exhibition allows visitors to discern some answers, balancing moments of hostility and racism with times when the public in Britain stood up, united and fought racism. In the late 1970s, for example (and one more of the seven ‘migration moments’), when racial tension was particularly high, people took to the street in thousands, united under the banner of Rock against Racism. For this migration moment (1978) there is a wealth of archive material and artworks that has prompted visitors to reflect on the racist attitudes of much-admired public figures such as Eric Clapton at the time, the role that grassroots cultural movements can play in changing attitudes, and to consider the need for similar grassroots movement now. Statements hanging from the ceiling provide first-hand testimony of many at the time. It is fascinating to see the reaction of younger visitors, many of whom were unaware of this historical moment, as well as those of people actively involved at the time. Whether they are learning or remembering, it feels like the exhibition is having an immediate, tangible impact.

No Turning Back is indeed a powerful exhibition, effective in addressing crucial themes around migration and encouraging the public to learn, engage and develop informed opinions. Through historical narratives and artworks visitors are given the tools to engage with and challenge many contemporary migration myths and misconceptions. In doing this, the exhibition contributes to the recommendations provided by the latest Home Affairs Committee report: ‘We cannot stress enough the importance of action to prevent escalating division, polarisation, anger or misinformation on an issue like immigration. To fail to address this risks doing long-term damage to the social fabric, economy and politics of the United Kingdom.’

Having a Migration Museum in which Brits and non-Brits alike can learn about and interact with this country’s history of migration is more important now than ever before – particularly when the debate around migration is so intense and people are showing a willingness to engage constructively.

Assunta Nicolini is working on migration and asylum in conflict areas while completing her doctoral studies at City University, London.