Human Cargo

One of our core ambitions has always been to tell the long story of migration into and out of this country – partly because every immigrant into one country is an emigrant from another, and partly because people forget that, until the 1970s, the United Kingdom was a net exporter of people: more people left the country than entered it. The story of emigration from this country is fascinating and often horrific – and the parallels between ‘then’ and now are all too obvious. In this guest blog, Matthew Crampton, writer and folk singer (whose latest book is Human Cargo: Stories and Songs of Emigration, Slavery and Transportation), tells some of these stories and shows how folk song can allow the voice of people caught up in this practice to be heard.

Behind every statistic, a human story

Every statistic I read on migration suggests it brings economic benefits to a host country. Yet most newspaper headlines damn migrants. How do we bridge this disconnect? It’s not enough to state facts. People love their myths. Moreover, those on both sides of the argument tend to view migrants solely as statistics. Maybe story, and song, can help us re-frame the discussion.

A quayside departure – the young man has just been ‘pressed’ into joining a ship headed for the colonies.

If you look at the lives of those trafficked* or transported in past centuries – particularly in the 1700s and 1800s – you see clear parallels with today. Patterns of cruelty do not change. In 1800, for example, frightened families filled the dockside of the Scottish town of Fort William. They were escaping famine, disease and landlords. Like Syrian families today, they were prey to the slick promises of unscrupulous traffickers, such as agent George Dunoon. He promised comfortable passage to America. Yet he crammed the desperate emigrants into rotten hulks. The crossing was horrific. The death rates for emigrants – though paying passengers – were sometimes higher than on slave boats. How could this be?

The answer, depressingly, is an economic one. Slavers were paid for the cargo they delivered alive; however cruelly the slaves who constituted this cargo might be treated, they were of value to slavers only if they survived the crossing. Emigrant captains, by contrast, were paid in advance, so they had less incentive to keep their cargo breathing. Indeed, the more that died, the more space, and food, for those left behind. Of course there was no moral equivalence: most emigrants, however desperate their circumstances, travelled voluntarily; slaves were transported against their will. And emigrants who survived, and arrived, were often free citizens, not slaves – whereas there was no such freedom for any slave who survived the journey.

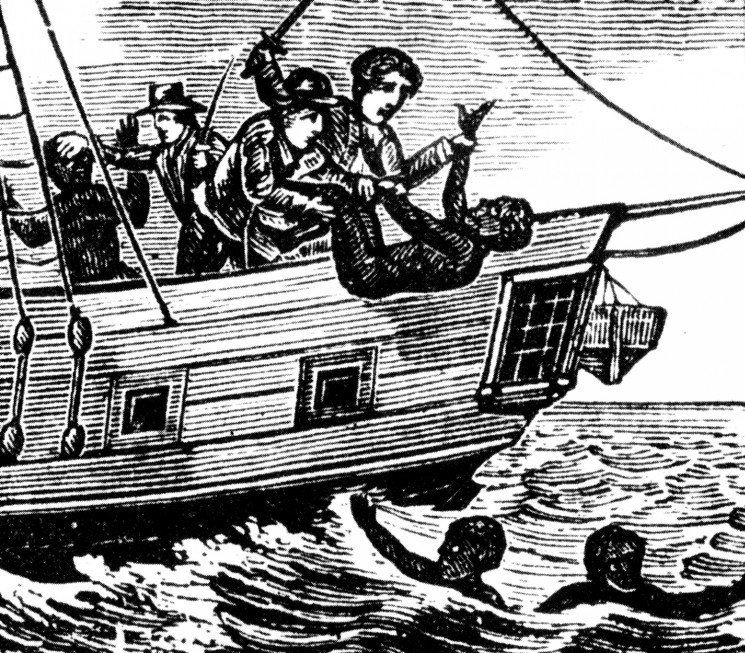

Sex slavery was a common feature of the 18th and 19th century slave trade, occasionally, as here, featuring white women.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw millions of people on the move, a greater proportion of the then populations than today (though Syria is re-balancing the equation). And many of those people were Europeans. It’s estimated that nearly one third of the German-speaking adult population of Europe – some 15 million in total – migrated during the 1700s.

Tiny Britain had seized huge colonies, and needed labour to exploit this new land. Slaves were to provide much of this labour, particularly after the slave trade became highly sophisticated in the latter half of the 18th century. Before that, Britain also exported political prisoners to work the colonies, with Oliver Cromwell sending thousands of Scottish and Irish prisoners to the Carolinas (on the east coast of America). Later, the British government sent felons: you could be transported for 14 years for as small an offence as stealing a loaf of bread. This provided significant labour, at first to America, and then, after US independence, to Australia.

In any case, the majority of Europeans arriving in colonial America were indentured servants. Such servants entered a contract to work for another person for a defined period of time, usually without pay but in exchange for free passage to the new country; they could be bought or sold and, on average, they did not survive their period of indenture. But many did survive, like the remarkable Peter Williamson. He was kidnapped aged ten in Scotland, then ‘spirited away’ to be sold as a servant in South Carolina.

While playing on Aberdeen quay, he later wrote, ‘I was taken notice of by two fellows belonging to a vessel in the harbour, employed by some worthy men of the town, in that villainous and execrable practice called kidnapping.’ Such traffickers, known as ‘spirits’ (hence ‘spirited away’), sold him in Philadelphia – for sixteen pounds – for seven years’ indenture on a plantation. Much of that money would have made its way back to the Aberdeen magistrate who helped organise the seizure.

There are many such stories of human cargo from the time.

The Highland Clearances, undertaken in the 18th and 19th centuries by unscrupulous landowners seeking to change the use of the land from agriculture to sheep farming, was the source of a huge movement of people from the heart of Scotland to the large towns and, further afield, to the British colonies. In its wake, abandoned crofts were the only record of a once-thriving Gaelic community.

Catherine McPhee was ‘cleared’† by her Hebridean landlord, who gave her just hours to pack up her life before forcing her onto a boat, next stop Nova Scotia. James M’Lean was an American sailor, pressed into the Royal Navy and forced into many years of horrific service across the world. Robert Whyte wrote a chilling account of life (and death) aboard an Irish ‘coffin ship’ bearing emigrants to America, which was later published as Robert Whyte’s 1847 Famine Ship Diary: The Journey of an Irish Coffin Ship.

And Olaudah Equiano provided us (in his 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano) with a rare first-hand slave’s account of the Middle Passage from Africa to America. He wrote ‘It was said the stench of a slave ship was so strong that other sailors could smell it a mile downwind, and that the odour of vomit, sweat and faeces of its human cargo worked its way into the very wood and could not be scrubbed away.’

Olaudah Equiano was instrumental in drawing to public attention the horrific 1781 massacre of African slaves on the slave ship ‘Zong’. The ship’s crew threw 133 Africans over board when the ship ran low on drinkable water – but also to cash in on insurance repayments for the ‘loss’ of the ship’s cargo. The case against the ship owners was unsuccessful but is said to have led to the abolitionist movement in Britain.

These stories help humanise the history of migration. But history tends to record the rich, the resourceful and the lucky. What of the masses, the poor or illiterate, who left no testimony?

Here, interestingly, we can turn to folk song. Vast numbers of folk songs exist from this period. They’re mostly anonymous, passed down orally until transcribed by a song collector. Or they were printed crudely on broadsheets, sold cheaply in the streets of Hanoverian or Victorian England.

Though anonymous, folk songs can provide an authentic record of ordinary people. There’s a song called “Paddy’s Lamentation”, or “By the Hush”, whose chorus sings:

Oh you boys, now take my advice

To America I’d have you not be coming

For there’s nothing here but war,

And the thundering cannons roar,

And I wish I was back home in dear old Ireland.

Union flag and cannon – on their arrival in America, many indentured servants found themselves drafted in to fight on behalf of the Unionist cause.

“Paddy’s Lamentation” highlights a little-known story about migration from the time. During the American Civil War, the Union Army sent recruiting agents to post-famine Ireland. They promised free Atlantic passage to young men, in return for a bit of work. On arrival in New York, all excited, the men would not be allowed to disembark until they’d signed up to join the army of the northern states. Within months, or weeks, they might be on the battlefield of Gettysburg, where, like the narrator of this song, they lost a leg, or worse.

Migrants who’d survived the crossing could not depend on Trip Advisor to chronicle their duplicitous traffickers. But word could reach back home with songs like this.

For my book Human Cargo, I found many such stories, and songs, which chart the breadth of migration in past centuries. These touch areas such as emigration, slavery, the press gang, sex trafficking and convict transportation. Where possible, I’ve included modern testimony, for example contrasting a trafficked Japanese sex worker from 1905 with the recent experience of a young Albanian woman lured into Italy. Or I link the vicious practices of the press gang with the recruitment of African child soldiers today.

As I say in the introduction, today’s refugee crisis demands witness – and action – but is hard to grasp. Story and song won’t solve the problems, but they can help find a way in.

*The terms ‘trafficking’ and ‘transportation’ in the 18th and 19th centuries include those carried involuntarily – such as slaves, prisoners and the forcibly displaced – and those travelling by choice (even if it was a desperate choice), such as most emigrants.

†Another way of saying ‘forcibly displaced’ – this process, which took place over a period of 100 years in the 18th and 19th centuries, is now referrred to as the Highland Clearances.

Matthew Crampton’s book, Human Cargo: Stories and Songs of Emigration, Slavery and Transportation, is available for £10 – more info here. The pictures accompanying this article come from the 50 illustrations in the book.