15 May, 2018

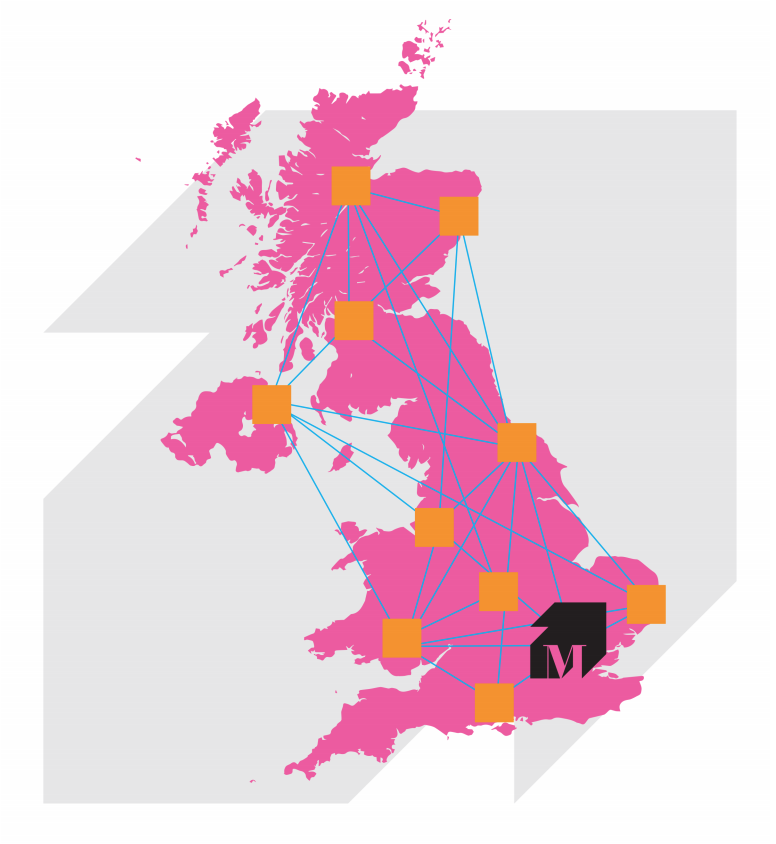

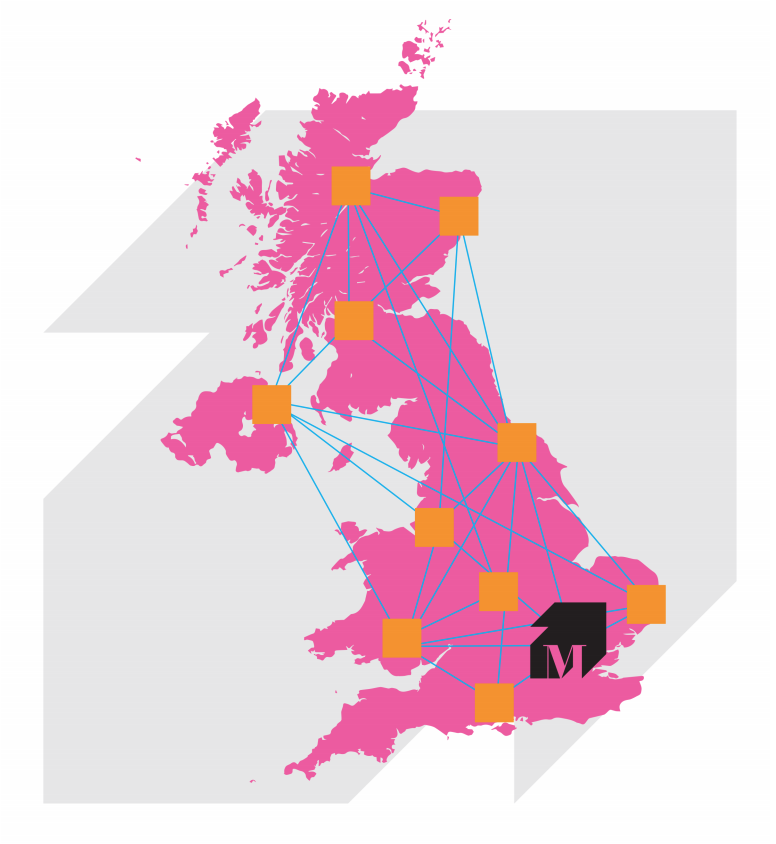

From November 2016 to November 2017, we coordinated the pilot year of the Migration Museums Network, generously funded by Arts Council England and Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

This network pilot aimed to increase and improve outputs associated with migration and related themes in museums and galleries across the UK. Various activities met these aims: a widespread online survey about migration themes in our sector was completed by 119 respondents from a range of institutions across the UK. We delivered a report, co-authored by Dr Cathy Ross and Emma Shapiro on the status of migration themes across the sector; updating previous research from 2009 with lots of new information and highlights. We also held two events in the autumn of 2017, focused on sharing best practice, highlighting case studies and facilitating partnerships across the sector. One was at the British Museum in London with 80 delegates; the other was at the Discovery Museum in Newcastle with 40 delegates. Thanks to all those who participated in the events.

Evaluation of the pilot was positive, with participants expressing strong demand for an information-sharing network on migration themes and giving positive feedback on the two events held to date. The overwhelming majority of survey respondents and delegates expressed a clear desire to be part of a Migration Museums Network, and to share contact and project details, via Network events, and online.

For more information and to read the report, survey and evaluation findings in full, please click on the links below:

Download and read the Migration Museums Network 2017 Evaluation report

Download and read the report on the Migration Museums Network survey results 2017

Download and read the Museums and Migration 2009-17 report

To find out more about the pilot of the Migration Museums Network and explore possible next steps for this network, please contact our Head of Learning and Partnerships Emily Miller: Emily@migrationmuseum.org

24 October, 2017

In the third of our series reflecting on the experience of running workshops with young people and schoolchildren, Sarah Crafter (The Open University) and Humera Iqbal (University College London) talk about a project that has as its focus young people and children who act as interpreters for their parents and families – and how this focus can enhance the empathetic understanding of pupils (the vast majority) who are not migrants themselves.

Animation and image by Alan Fentiman: http://bit.ly/2aVfHYw

‘When I was small and I moved in Milan, I used to live with my parents and uncles. I have really good memories with them until the age of 12. Unfortunately, I had to move to the UK, and they couldn’t come. This event changed me and the way I act.’ Safi, aged 15, (Bangladesh, Italy, UK)

Safi, aged 15, moved to Britain three years ago from Italy, having previously lived in Bangladesh. His childhood had been full of instances of resettlement. When young people, like Safi, migrate to a new country, they can often be left with a sense of loss: for people left behind and places they loved. At the same time, they can face new challenges in their new setting; getting to know new people, learning the language, culture, systems and structures in the new country.

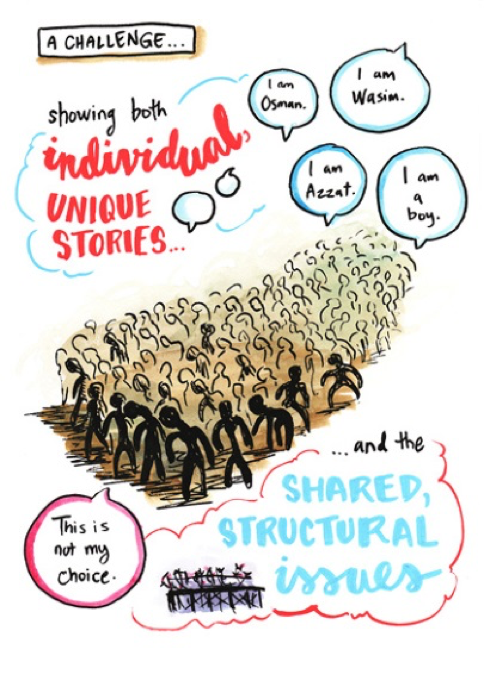

We explored some of these themes at the workshop we ran in 2016 for the Migration Museum Project with a group of 65 local schoolchildren at their exhibition Call Me by My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond. For quite some time we have been working with children and young people who have migrated with their families to a new setting in which they act as child language brokers – children and young people who interpret and translate for family and friends who can’t speak English. Over the years we have learnt that young people translate across lots of different situations and places like doctor’s surgeries, schools, banks, shops and workplaces. Sometimes they really enjoy being a young translator and take great pride in being able to help their families and friends. In other instances the conversations are difficult and people are not always very sympathetic. Many of the young people we speak to tell us, just as Safi did, how difficult it was to arrive in a new country and not be able to understand what people were saying. This sense of change and loss was also explored in the Call Me By My Name exhibition in relation to refugees, and we were able to identify many similarities between the exhibition and our research.

We built on some of these themes in the workshop. We asked the pupils to think about what it feels like to migrate, to be in a new place, to go into the unknown and to learn to communicate when there is no shared language. We started by showing a short animation from our research which features the voices of young people speaking about arriving in a new place and translating.

After watching the film, the young people gathered into groups to talk about some of the main themes that had arisen. This was quite a difficult task for some people, especially if they hadn’t experienced or thought about what it might mean to be a young translator or to migrate to a new country.

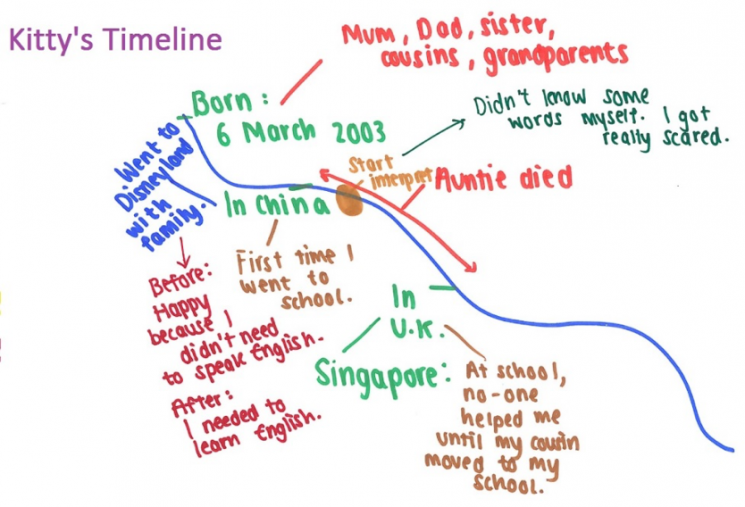

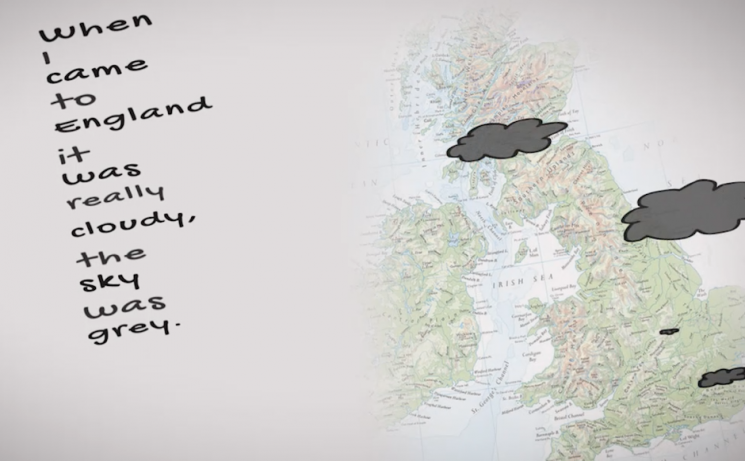

Yet, in truth, most of us can pinpoint a situation or feeling of being ‘out of place’ or alone, or unable to say what is in our minds. We wanted everyone to be able to capture that feeling and, to do that, we asked the pupils to put together a timeline map of their own experiences (working with timelines being something we have done in our research). We showed a timeline map made by a teenager called Kitty, who had migrated from Hong Kong to the UK with her family. It captured many markers of upheaval as well as instances of emotional change in different stages of Kitty’s life.

Using Kitty’s narrative as inspiration, the workshop pupils were asked to draw their own timeline, starting with the places they had lived or the places they had moved to (a house, a street, a country). The pupils then added people in their ‘migration timeline’ to get a sense of those who are always with us, those who come into our lives and those who fade out. Languages learnt and spoken were added. The pupils were encouraged to describe any ‘firsts’ they had experienced, such as the first time riding a bike, trying a particular food, reading something that made them cry.

This workshop was useful for the pupils because it enabled those who had never migrated to a new country, or learnt a new language, to gain a greater depth of empathy and understanding about how this must feel. In loading memories of newness, change, experience and important relationships, the pupils were encouraged to explore what their own feelings might be in moving to a new country and learning a new language. Our workshop also helped those pupils who had migrated, and who did speak a second language, to talk freely about their experience with their friends. We were impressed with how bravely they spoke to us, and their friends, about what that felt like for them. Teachers might also use similar exercises or prompts within school during citizenship and personal health and healthcare lessons, to explore issues of diversity.

You can find more information about our project here.

Dr Sarah Crafter is a senior lecturer in the Department of Psychology at the Open University in the UK. She has a PhD in Cultural Psychology and Human Development and is interested in cultural identity development and ‘non-normative’ childhoods. Her work with child language brokers grew out of broader interest in the constructions or representations of childhood in culturally diverse settings. Dr Humera Iqbal is a lecturer in psychology at the Department of Social Science at University College London. She is interested in identity and the migration experiences of families and young people, in particular how they engage with institutions in new settings. She is also interested in mental health and wellbeing in young people, particularly those from minority groups. Her research uses mixed methods as well as arts- and film-based methods.

18 October, 2017

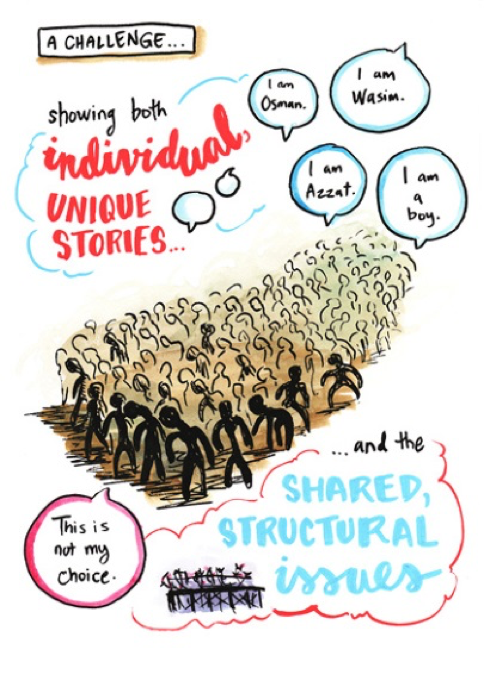

In the second of three blogs on holding workshops with school pupils on the issues of migration, Umut Erel and Elizabeth Newcombe discuss an attempt to introduce pupils to the complexities of the language and the policy issues surrounding immigration, at a time of great global inequality and economic recession.

When holding a workshop for a school from Sussex at the Migration Museum Project’s Call Me By My Name exhibition in July 2017, it was striking to see school pupils becoming passionately engaged with issues of migration. The group of 15 pupils and their teachers arrived on one of the hottest days of the year, having already spent time wandering through London. Emily Miller, MMP’s head of learning and partnerships, started the workshop with an interactive game, using questions and movement in the space of the museum to break the ice and find out how everyone relates to migration. Some of the questions she asked were:

- Do you know someone who has migrated?

- Do you speak more than one language?

- Has anyone in your family migrated?

If our answer to these questions was ‘yes’, we had to take a step forward; if the answer was ‘no’, we were asked to take a step backwards. Soon most of us were concentrated in a tight circle in the middle of the room, and it had become clear that there was a lot of experience of migration, whether personal or indirect.

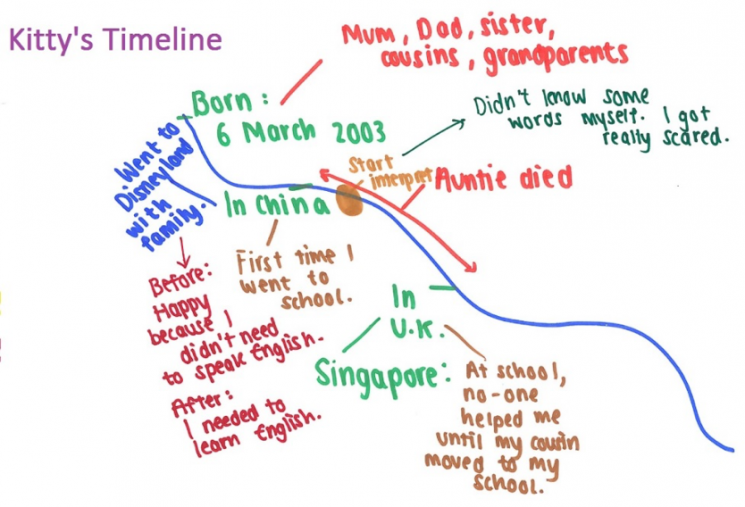

Drawing by Laura Sorvala.

The workshop then moved on to look at some of the key terms in the migration debate. A young refugee told of his experiences of migration, finding his way around life in the UK and how he now works in arts and education organisations in which he initiates dialogues on the experiences of refugees and migrants. All of us were stunned to hear of the difficulties he had overcome on his journey to the UK in the early 2000s. Some of the pupils shared their personal experiences of the country he came from and the countries he had passed through, which gave the encounter added poignancy.

After this informative and emotionally charged part of the workshop, we changed gears slightly and introduced a more academic take on the issues. Starting with an interactive exercise on global inequalities of income, we began to question the term migrant, pointing out that, when we use the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’, this does not refer to a legal figure or a dataset, but to a political figure. We discussed how British people living abroad almost always think of themselves as ‘expats’ not ‘migrants’, while Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people who were born and have lived all their lives in the UK are often called ‘second generation migrants’. So, the decision about who counts as a migrant is often framed by assumptions about race, class and nationality.

When discussing migration, we often hear about the need to protect the welfare state from outsiders, but how can we understand the welfare state against the backdrop of global inequalities? We are living at a time of the highest level of global inequality in human history, when the wealth of 67 people is the same as the combined total of the world’s 3.5 billion poorest people, and the poorest 50 per cent of the world have 6.6 per cent of total global income. There are issues with the methodology of these estimates, but it cannot be denied that the world has changed from the 19th century. Today, for most people in the world, what is key to your life chances is the country you live in. The fear for those living in wealthier states is that there are a lot of people who are hard up in the world and that, if you don’t have much, you need to hold on to it.

Photo of the PASAR project’s ‘From Margins to Centre Stage’ workshop, February 2017 © Marcia Chandra.

Migrant families’ exclusion from the welfare state was a topic in another research project – Participation Arts and Social Action in Research (PASAR) – we are currently running with our colleagues Erene Kaptani (Open University), Maggie O’Neill (University of York) and Tracey Reynolds (University of Greenwich). The PASAR project conducted participatory research with migrant mothers affected by the policy No Recourse to Public Funding (NRPF), which means migrants who are subject to immigration control are not allowed to access benefits, tax credits or housing assistance. This policy affects both migrants who have the right to remain in the UK and those who are undocumented. The policy pushes these migrant families – many of whom include young children, who are among the most vulnerable people – to the margins of society through poverty and racism. In a workshop with policy makers, practitioners and activists, we worked with a group of migrant mothers affected by NRPF to enable their collective voice to be heard. To do so, we showed a short theatre piece developed through the research.

Photo from PASAR project theatre scene © Marcia Chandra.

At the schools’ workshop, we watched a short scene from this theatre piece about Elaine’s experience. Elaine had been working for many years for a large supermarket. She needed to take time off every two weeks to sign into the Immigration Reporting Centre, a requirement of the Home Office. Her manager used his knowledge of her vulnerability to bully her and change her onto an unfavourable night shift, even though she had just had a baby. Her union representative’s response was that as an immigrant she should be glad to have a job. She also experienced stigmatisation by fellow workers, who saw her as an ‘illegal’ immigrant. Eventually, she lost her job – unable to pay rent, Elaine, her husband and six-year-old son have for four years now been living in the houses of friends and acquaintances, surviving on their monetary support.

This example shows how racism, anti-immigration policies and austerity intersect. An increasingly hostile climate to immigration has made it more difficult for migrants to find formal and informal employment. As a consequence of increasingly stringent migration regulations, particularly since 2012, more and more migrant families are subject to migration control, prevented from accessing public funds and rendered unable to economically support themselves (Price and Spencer, 2015). In a situation of crisis – through the loss of jobs or accommodation, relationship breakdown or health problems – they cannot draw on the relative safety net of the welfare state to help them overcome these points of crisis and are pushed more and more to the margins of society.

Having watched a short video clip of these theatre scenes with the school pupils, we had an interesting discussion about some of the issues raised by Elaine’s story:

- How can labels such as ‘illegal migrant’ be misleading and stigmatising?

- Why are some people, and not others, allowed to draw on welfare services?

- Should contributions through work be the criterion for deciding whether migrants can participate in the welfare state?

- Should there be other criteria for inclusion into welfare, based on colonial and postcolonial ties?

- Should there be criteria based on shared humanity?

It is hard to summarise the workshop, as it was rich and varied, but it seems to me that this variety of modes of engagement (personal testimony, interactive activities, and audio-visual material and information) has been fruitful in raising many questions, showing the complexity of issues of migration and welfare, and linking conceptual discussions to personal experiences of migration, which are often far richer than those portrayed in public debate. While teachers challenged us as academics to present information in accessible ways, especially for pupils who are still learning English, their feedback was heartening: ‘Our students learnt a lot from the experience both about migration at the human level but also the bigger picture of why these issues are so pressing for the UK at the present time. A great day well spent!’

Reference

Price, Jonathan, and Spencer, Sarah (2015) Safeguarding Children from Destitution: Local Authority Responses to Families with ‘No Recourse to Public Funding’. Oxford: COMPAS.

Umut Erel is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the Open University. She is Principal Investigator of PASAR, an ESRC-funded research project investigating the opportunities and challenges of using participatory theatre and walking methods for social research.

Emma Newcombe is the Head of External Relations for COMPAS and the Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity. She oversees all COMPAS’s communications work, and also supports the development of the ESRC Urban Transformations project. She has an MA in Migration Studies from the University of Sussex and a BSc in Social Policy from the University of Bristol.

2 December, 2016

The Migration Museum Project (MMP) is jointly hosting a civil society forum at Rich Mix, London, on December 2, from 10am – 2pm, exploring the evolving impact of and response to refugee and migrant issues worldwide.

The evolving dynamics of the refugee and migrant response is a showcase event and panel discussion hosted by MMP, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), The Open University, The University of Oxford’s Centre for Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS) and actREAL.

The event will feature selected works from the MMP’s Call me by my name: stories from Calais and beyond exhibition, as well as a panel discussion exploring the ethos and ethics of adequate responses to the current refugee and migrant situation, and where responsibility for these responses should lie.

There will also be live illustration of the panel by graphic artist Laura Sorvala, and a performance by school students based on material devised during a series of education workshops run by actREAL, an organisation using theatre and performance to bring academic research on social issues to life.

The event marks the culmination of The ethics and politics of the refugee crisis, an integrated programme of activities about migration aimed at strengthening collaboration between academic research, civil society, education and the culture sectors via avenues of creative expression. The programme is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Admission is free, but registration is required. For enquiries or to book a place, please visit the Eventbrite page.

Exhibition:

Extracts from Call me by my name: stories from Calais and beyond

Performance:

Students from City and Islington College, exploring media representations of migration and the Calais camp, based on a series of workshops run by actREAL

Live illustration:

Laura Sorvala