Phoenix City: the resilience of London

In this period of enforced inactivity, when almost all Migration Museum staff are in furlough, we are running a small number of blogs written by friends of the Museum on subjects related to the current pandemic. The first one, written by Cathy Ross, long-term friend (and distinguished friend) of the Museum, focuses on the capacity of our capital city to regenerate itself after disasters; future blog posts will move the discussion outside London.

London is resilient.

How do we know? History says so. My favourite London historian, the late Roy Porter, says that historians make ‘rotten physicians, worse planners and appalling prophets’, but nevertheless most of them agree that London has the resilience gene embedded deep in its DNA. It is a demonstrable fact that the city has bounced back from whatever disaster life has thrown at it. Today, London can look back on a life story packed with catastrophic experiences: invasion, sacking and pillage, Black Death, plague, war, fire, more plague, riots, more fire, floods, population flight, urban decay and Blitz bombs. London has survived the lot.

London during the Blitz: Number 23 Queen Victoria Street, City of London, collapsing in flames on Sunday 11 May 1941 © City of London London Metropolitan Archives

So why is London so resilient? Or, to use a metaphor that we’re all a bit too familiar with today, what makes its immune system so strong? When Roy Porter was writing his wonderful book London: A Social History in the early 1990s, he mused on London’s lucky genes. The two he saw as fundamental were: ‘its geographical site with respect to Europe and the Atlantic’ – which made the city perfectly suited to world trade and therefore in-coming wealth; and ‘its cohesive population’, by which he meant that, despite the inequality that inevitably exists in cities, ‘divisions between rich and poor remained bridgeable in London’. (Whether this is as true now as it may have been when Porter was writing would make for an interesting debate . . . )

It was the strength of these two long-term factors which counteracted any short-term failings in London’s top–down government (in a particularly bumbling state at the time Porter was writing):

Over the centuries London’s government was bumble and bungle; internal confusion on a day to day basis, and paralysis at times of crisis – the Plague, the Fire, the Gordon Riots, even the Blitz. In the past, the failures – structural and personal – of London’s government have been neutralised by the socially redemptive power of its trading position and the cohesiveness of its population.

Roy Porter, London: A Social History, Hamish Hamilton (1994)

Of course, it hardly needs to be said that London’s two lucky genes are both about movement: movement of goods, movement of people through society, movement of ideas and encounters. These are the processes of change and development which drive any city forward and always prove stronger in the long term than any determination to stand still. Migration is well and truly part of London’s immune system. Without migration, London’s resilience would be compromised.

A crude measure of a city’s resilience is whether people still want to live in it after the catastrophe has happened. By that measure, London proved super-resilient after the outbreak of Plague in 1665. Famously, the Great Plague emptied the streets and terrified the inhabitants (‘I went all along the city and suburbs … a dismal passage, and dangerous to see so many coffins exposed in the streets, now thin of people; the shops shut up, and all in mournful silence, not knowing whose turn might be next,’ cried John Evelyn). Despite killing one in six Londoners – probably around 80–100,000 people, the Plague scarcely dented London’s relentless growth. Population statistics for pre-19th century London are notoriously unreliable but it is probably fair to guesstimate the population in 1600 as around 200,000. By mid-century it had doubled to around 400,000. By 1700, despite plague, fire, war with the Dutch, etc., the population had swelled to nearer 600,000 people and London was well on the way to becoming Europe’s monster city.

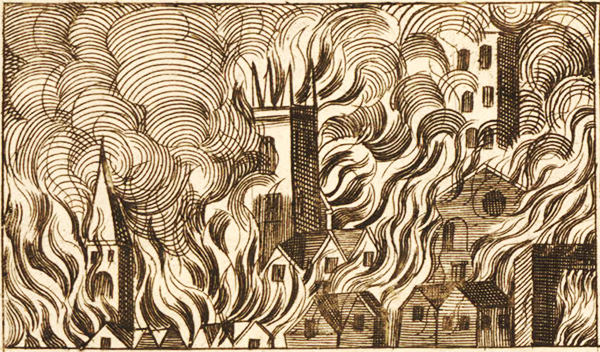

London in flames: ‘This view represents Ludgate as having just caught fire; behind is the Cathedral of St Paul, involved in flames, and the extremity of the scene exhibits the ancient and beautiful arched tower of St Mary le Bow surrounded by the burning ruins of the desolated city.’ From an engraving by Robert Wilkinson, 1811 © British Museum

After the more recent catastrophe of the Second World War, London’s population took longer to recover – surprisingly long: it was not until 2015 that the population of Greater London returned to the 8.6 million it had been in 1939. In the 1960s and 1970s there were still many who believed that London was in its death throes, its declining population a sure sign that vital organs were shutting down. But London in the 1960s is a reminder that resilience is not just about statistics. Demographically, London was indeed ‘dying’ in the 1960s, but that was not the only story in town during that effervescent decade. The better-known story of 1960s’ London is of a city coming alive with new optimism and energy, a very clear illustration of another historical truth about catastrophes, which is that they are invariably catalysts of change. Terrible events force people to learn lessons and contemplate doing things differently, if only to avoid a repeat of the terrible events.

Two survivors from 17th-century London (the Monument and St Magnus Church) surrounded by buildings from the 1920s, 1960s and 1990s (© Cathy Ross, photographed in 2011)

So can we speculate about London’s resilience after the great pandemic pandemonium of 2020? A while back, it used to be fashionable for historians to play the ‘What If?’ game. What if Henry VIII hadn’t fancied Anne Boleyn? What if the Black Death hadn’t happened in 1348? It’s possible to stretch this game quite far: thus, if the Black Death hadn’t happened, maybe we wouldn’t have ended up with a National Health Service in 1945.

Speculating on the ‘What if an event hadn’t happened?’ is really thinking about the long-term consequences about what actually did happen. So if we speculate on the ‘what if’ of coronavirus – what if the virus had not knocked the stuffing out of London in 2020? – we might conclude that in the long term the virus will strengthen civic resilience. As we all know, historians make appalling prophets, but I’d like to think that this traumatic and sorrow-filled episode will ultimately provoke a new reflection on what makes London London, and a new appreciation of the importance migration plays in our city’s resilience.

Dr Cathy Ross is a long-term friend, and distinguished friend, of the Migration Museum. She has worked in museums most of her career, most recently as Honorary Research Fellow at the Museum of London, and was responsible for curating our Germans in Britain exhibition, which toured the country non-stop from 2014 to 2016.