Archives

11 April, 2018

For many people, there was a golden age when Britain was truly British, populated by the British, with shared cultural and religious values. This golden age is variously identified as that of King Arthur, or Elizabeth I or Victoria, or Churchill, among others. As is the case with most golden ages, all too often the evidence fails to support the myth. In the early nineteenth century, for example, the number of Germans in London was considerable (28,644out of a total population of 2.8 million, as recorded in the census of 1861, the first in which Londoners’ country of origin was sought) – but how diverse was the capital generally? This was a question explored by students at the University of Hertfordshire, and Adam Crymble, senior lecturer at that university, here discusses two illustrations taken from their findings.

Final year history students at the University of Hertfordshire went looking for images of London’s diversity in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and had no trouble finding a veritable treasure trove. The images were brought together from already-digitised collections and shared via an Instagram feed that showcases not only Britain’s diversity but also some of the challenges and attitudes faced by migrant groups over the centuries.

The project asked students to consider what migration meant to the UK two hundred years ago. It proved a fabulous complement to the ‘What does migration mean in the UK today?’ poster project by our colleagues down the corridor, which is still on display at the Migration Museum.

It can be easy to forget about London’s long history with migration. The dominant narrative is that migration to the UK began in earnest in 1948, when the HMT Empire Windrush landed on British shores, discharging hundreds of Caribbean migrants and kicking off a wave of post-war immigration. But a quick trip into the digital archive of Scotch–London cartoonists George and Isaac Robert Cruickshank show that a diverse London stretches much deeper into the past.

‘Tom and Jerry “Masquerading it” among the Cadgers in the “Back Slums” in the Holy Land’ (1821), drawn and engraved by Isaac Robert Cruikshank and George Cruikshank (Public Domain, from the British Library collection).

During the course of their studies, students found two images from the Cruickshanks’ ‘Tom and Jerry’ series that are particularly illustrative of that fact. In 1821, the fictional English gentlemen Tom and Jerry, on their romp about town, delved into London’s most Irish space: the neighbourhood known as the Rookery of St Giles-in-the-Fields in the west end. Today it is but a stone’s throw from Tottenham Court Station and the site of Google’s London offices. Two hundred years ago, however, it was a tangle of streets and a slum that many people feared to enter. Sometimes it was referred to as the ‘Holy Land’ – a tongue-in-cheek reference to the high concentration of Irish Catholics in the region and the ironically unholy behaviour to be found therein. It was described as a ‘rabbit warren’ of narrow passages and dangerously overcrowded houses where tenants rented a shared bed or a space on the bare floorboards for as little as 1p a night.

It was among these ‘cadgers’ that Tom and Jerry spent their evening in St Giles, in one of the area’s infamous subterranean public houses. The pair witnessed the locals in their evening revelry after a hard day of begging and stealing, followed by a night of hard drinking, singing, and fighting away their daily take. The poor people of St Giles lived for the moment. With no way to safely store valuables, they knew that a day that ended penniless was a night safe from robbery.

Tom and Jerry undoubtedly heard a few Irish brogues as they worked the room that fictional night two centuries ago. But the Cruikshanks’ depiction of the scene reminds us of something else: this was a diverse and cosmopolitan space. Most of that diversity is invisible to us, but there are at least three black individuals in the painting who act as a clear reminder that London was home to many different migrant groups. Two of those black people are dressed as sailors, highlighting the important role played by international trade in bringing people to London from around the world. The arrival of those particular individuals was of course linked at least tangentially to the British trade in Africans, which had ceased only in 1807, when the slave trade was finally abolished in the British Empire. But dark-skinned faces from other parts of the world could also be found on London’s streets – ‘Lascar’ sailors from India, and East Asians arriving on the ships from China were part of daily life in London.

What’s particularly noticeable about the black individuals in the image is that they are simply part of the evening festivities. One of them is joining a fistfight in the back left, another plays the fiddle at centre, and the third is smoking a pipe around a table of fast friends at right. Apart from the fistfight, which seems to include a fairly large group of people, there’s no sign these black people are unwelcome in this space, nor should they be in such a multicultural part of town.

Diversity did not stop there. Facing the viewer in the bottom-left foreground is a man exhibiting physical characteristics used to denote Jewishness in nineteenth-century caricature. His presence is a reminder that the capital was also home to two Jewish populations: Ashkenazi and Sephardic. He reminds us that London was not an exclusively Christian city in the early nineteenth century. Nor was it solely Church of England. In addition to the large group of Irish Catholics in the Rookery, the tiny parish of St Giles was home to a Sardinian Catholic Chapel, attached to the Sardinian Embassy, and a place for the city’s Italian population to come together and worship.

Within minutes from where Tom and Jerry stood and just a few feet to the west of the parish boundary was the most French part of London – St Anne Soho, which was home to both French Catholics who had fled the French Revolution in the 1790s, and the descendants of the French Protestant Huguenots who had fled persecution almost exactly a century earlier, in 1685. One must wonder if any French voices echoed out among those cadgers in the room. If they had done, it certainly would not have been unusual.

It’s a shame the figures in the painting cannot speak, for if they could, their voices would ring forth a chorus of accents from up and down the country, from Glasgow to Cornwall and everywhere in-between. London was a melting pot of English migrants who joined these strangers from further afield and came together on unfamiliar streets, where they built new relationships. Many of the British internal migrants passed through St Giles and its Rookery, adding their accents to the fray.

‘Lowest Life in London. Tom, Jerry and Logic among the unsophisticated Sons and Daughters of Nature at “All Max” in the East’ (1821), drawn and engraved by Isaac Robert Cruikshank and George Cruikshank (Public Domain, from the British Library collection).

Diversity was of course not limited to St Giles. A few months earlier, Tom and Jerry had spent an evening in the city’s East End, at a popular working class dance hall. The scene is labelled ‘Lowest Life in London’, which acknowledges class and racial prejudices of the day, but also challenges those fears by depicting a joyful scene that showcases the coming together of cultures and a blending of classes. The wealthy Jerry cavorts with a well-travelled peg-legged sailor who plays a tune on his fiddle. A black woman in a colourful dress jigs with an Irishman, while a white person minds her on-looking baby.

These imaginary images showcased some of London’s most diverse spaces in the early nineteenth century. In subterranean public houses, and dancing clubs on the edge of town, diversity was on the fringes. But, importantly, it was present. Faces of every shade, and accents of every pitch and timbre, rang through London. Windows into that lost world presented through the escapades of Tom and Jerry remind us of just how deeply embedded migration is in London’s history. It seems unlikely that London has ever been a white, Protestant, English city.

Adam Crymble is a senior lecturer and historian of migration at the University of Hertfordshire. He is himself a migrant to London. The images discussed in this article were collected by his final year history students who contributed images of migration and diversity to an Instagram feed celebrating Britain’s diverse past. With special thanks to Ellen Daly for contributing the image of Tom and Jerry dancing at the ‘All Max’.

3 December, 2017

The Migration Museum Project is blessed with a large team of fantastic volunteers, without whom we would find it hard to function and impossible to run our events and exhibitions. Assunta Nicolini is one such volunteer, and her discussions with visitors to our current exhibition, No Turning Back, have got her thinking about a number of issues that she feels are raised by the display. This blog is the result of her thoughts and discussions around two of the seven moments of the exhibition: the arrival in this country of Huguenot refugees after 1685, and the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905.

No Turning Back: Seven migration moments that changed Britain introduces visitors to powerful artworks and archive images carefully interwoven to create a narrative that brings together past and present. It is within history that we so often find the key to understanding many of the social realities we inhabit today.

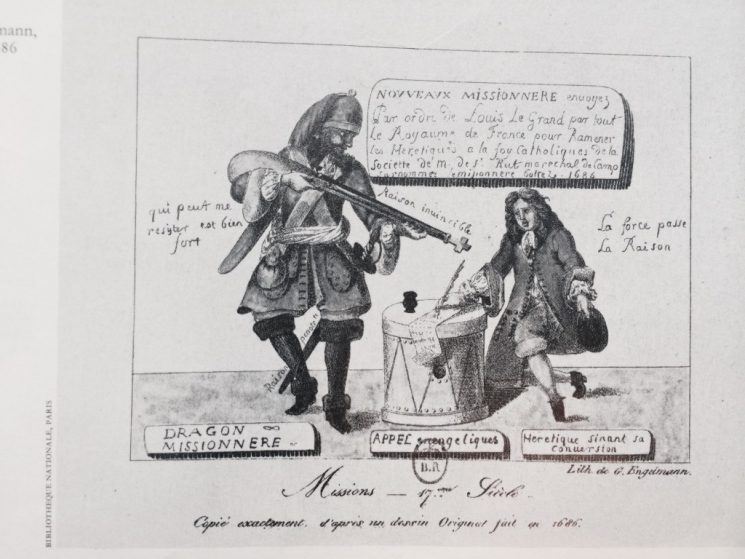

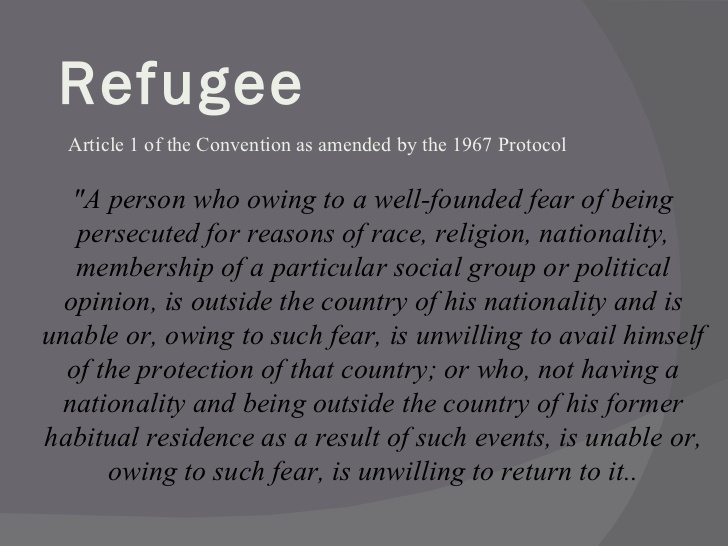

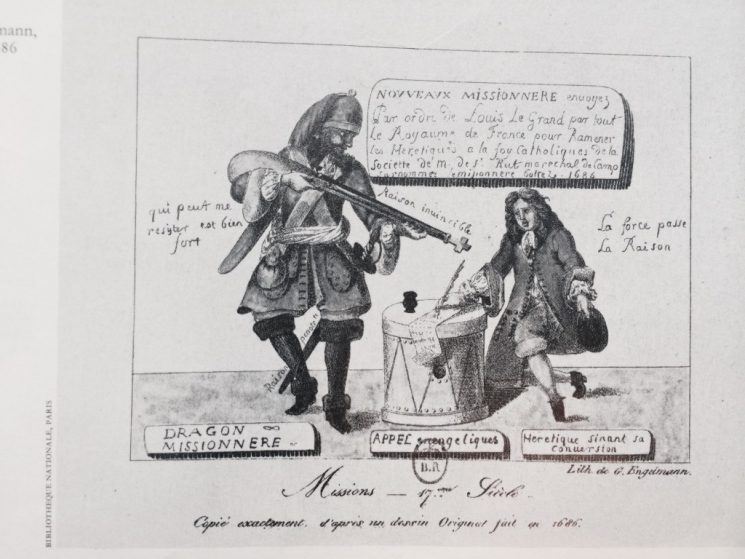

Migration is no exception. One of the seven moments shown in the exhibition, the year 1685, holds a particular relevance in the understanding of today’s migration dynamics.It was the year that France made Protestantism illegal, precipitating the arrival in Britain of about 50,000 French Protestant Huguenots. Centuries before the drafting of the Refugee Convention (1951), and with no legal framework in place establishing roles and responsibilities towards people escaping persecution, the term ‘refugee’ was introduced into the English language through the French Huguenots arriving on British soil in search of protection (refuge). It took about three centuries, a series of major humanitarian crises and, ultimately, the horror of the Holocaust for the international community to establish a legal framework aimed at giving protection to people fleeing persecution.

Article 1 of the United Nations’ 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

The history of the Huguenots in Britain is not, however, just about one of the largest refugee groups to seek safety and protection in this country. Their life experiences were not simply defined by their ‘refugee-ness’; on the contrary, their arrival and settlement offer just as important insights into the realities of migration.

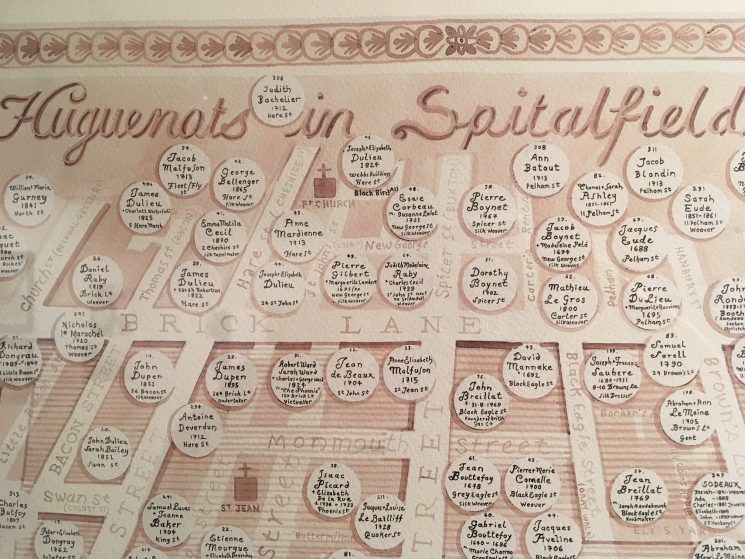

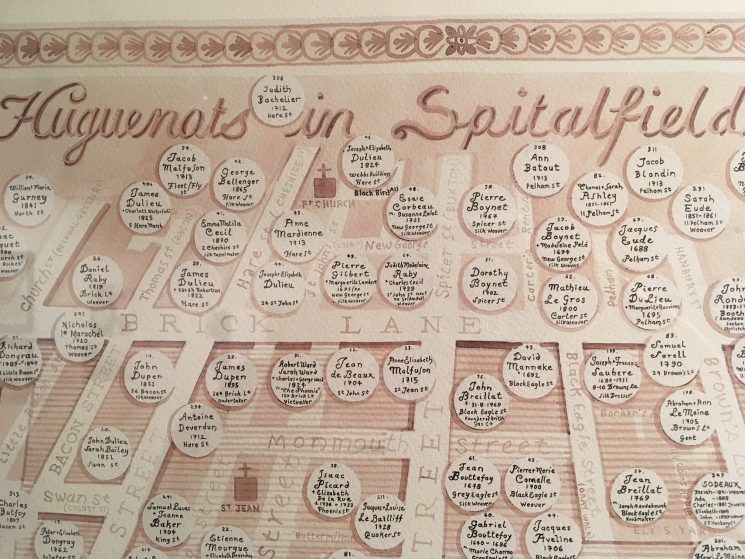

In the exhibition, Adam Dant’s delightful map representing this historical moment takes the curious eye of the visitor through a detailed drawing of the streets surrounding East London’s Spitalfields Market. Surnames of French origin are circled to indicate where the Huguenots were to be found. As visitors adjust their eye to these several locations, they then notice a further, more crucial detail. Surnames are accompanied by ‘professions’, mainly artisanal, such as weavers, clockmakers and silk merchants.

A detail from Adam Dant’s ‘Huguenots in Spitalfields’. A range of professions are readable in these circles, for example: ‘silk weaver’, ‘undertaker’, ‘victuailler’, ‘reed maker’ and ‘gent’. © Adam Dant

Such detail is crucial as it allows the visitor to expand their understanding of who these people were, beyond the one-dimensionality of their ‘refugee-ness’. Being given protection in Britain was not the end of the Huguenots’ ‘migration journey’ – settling and restarting their lives, as well as providing for their families, was just as important. Historical archives tell us that, although the Huguenots left France clandestinely and at short notice, taking little with them and with limited time for planning ahead, they were nevertheless aware that certain destinations were better than others. London, for example, offered not only protection but also great opportunities for employment and hence a better place to settle.

You don’t need to be an expert to spot the striking similarities with contemporary experiences of migration. Today’s refugees are no different from those of centuries ago – like them, they are human beings who, in order to have a life beyond survival, need to work. Obvious though this point is, the current obsession in the media and parliament is the apparent distinction between ‘refugee’ and ‘economic migrant’.

It is possible, however, to make such complexity simple, and to offer an accessible understanding of such migration dynamics. Migration experts have been drawing attention to the fact that immigration statuses – the classification of refugee, migrant or asylum seeker, for example – are never fixed but on the contrary are dynamic and mobile.1 Rigid legal categories labelling individuals either as migrants or refugees have become increasingly obsolete, as they fail to reflect the personal and global realities of contemporary migration.2 The stories of refugee-migrants themselves consistently show that people might start their journey as refugees but, like the Huguenots, become economic migrants later on. Scholars have widely recognised that contemporary migration is defined by its mixed nature and by continuity, rather than an opposition between forced and voluntary migration (see this video for Dr Nicholas van Hear’s clear outline of this matter).

The overlapping and mobility between immigration statuses is an aspect that was overlooked at the the time the Refugee Convention was drafted. Understandably, soon after the Second World War, the concern of the international community was focused predominantly on making sure that persecuted people would be protected outside their home countries. Economic migrants, on the other hand, could not benefit from a specific legal framework protecting their rights, since the ‘voluntary’ dimension of their migration implied they took responsibility for their own protection.

In recent decades, however, a greater emphasis has been placed on additional legal frameworks aimed at correcting the shortcomings of the Refugee Convention, in particular those based on International Human Rights law. A rights-based approach can in fact not only provide a framework for the protection of economic migrants but also enhance refugees’ protection, while at the same time establishing the universal human right to seek asylum.

Despite the availability of different legal frameworks governing migration and ‘refugee-ness’ today, there is no agreed position in policy making, advocacy and public opinion. Public opinion is characterised by narratives of ‘good and bad’ refugee-migrants, of ‘deserving and undeserving protection’, and of ‘inclusion and exclusion’. Refugees are mostly perceived as victims, but the moment they display willingness to economically improve their lives they are automatically seen as economic migrants and hence as undeserving of protection and support.

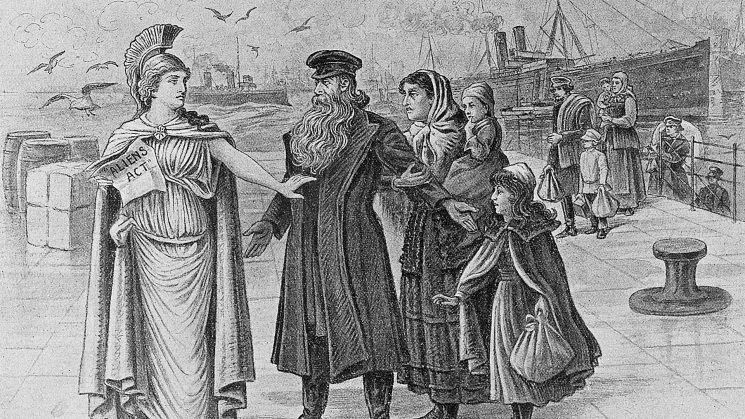

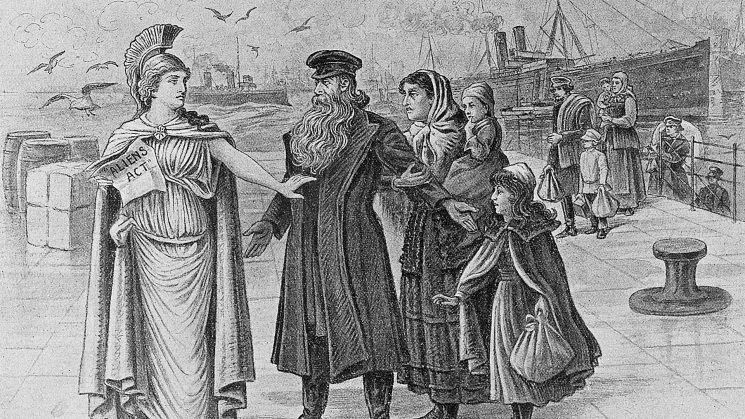

Satire on the Aliens Act – drawing of Britannia turning away a group of refugees who have just disembarked at a port, 1906. Part of the Migration Museum Project’s ‘No Turning Back’ exhibition. Image courtesy of the Jewish Museum.

Far from being new, this narrative partly finds its roots in another pivotal migration moment shown in the exhibition – 1905, when the Aliens Act was passed in Britain, the first legal framework regulating migration and based on the notion of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ immigrants. The Aliens Act was the result of rising nationalism based on disproportionate fear about newly arrived refugees, mainly Jews, and migrants of Asian origins. A satirical drawing from the time, showing Britannia saying ‘I can no longer offer shelter to fugitives; England is not a free country’, aptly describes the feeling of rejection felt by Jewish refugees. Another pamphlet from the archives directs the visitor’s attention to the fact that rejection was felt not only by refugees but also by immigrants, with trade unions attempting to dismantle the unfounded belief that migrants were competitors in the job market and bad for the British economy. Through the various details of this migration moment, the visitor is also encouraged to think about the importance of keeping labour migration channels open to refugees today.

History reminds us that looking at migration through rigid binaries of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’, ‘deserving’ and ‘economic’, risks reinforcing a dangerous divide that often underpins much of public opinion and policy making. What we witness today and the stories that migrants and refugees tell us bear a profound resemblance to the past and urge us to consider that a refugee-migrant should not be seen as a threat but rather as an asset to Britain and host countries in general.

1 See, for example, Schuster, L (2005) ‘The Continuing Mobility of Migrants in Italy: Shifting between Statuses and Places’. Oxford: COMPAS and Bloch (2011)

2 Zetter, R (2007) ‘More labels, fewer refugees: remaking the refugee label in an era of globalisation’, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 20, Issue 2, 1 June 2007, 172–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem011

24 May, 2017

Standing at a crossroads

What have been the pivotal moments, the forks in the road, the lines in the sand in the history of migration in this country? And was the referendum on 23 June 2016 one of those moments?

The pivotal moments in a person’s, or a country’s, life are always compelling hooks to hang narratives on, and fertile ground for speculation. What if Hitler hadn’t turned his attention away from Britain and towards the Soviet Union in 1941? What if the Spanish Armada had had better weather and organisation? What if King Harold hadn’t had to face the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge a mere three weeks before facing the Normans at Hastings? What if England hadn’t beaten Germany in the 1966 World Cup final? The bookshelves in the historical section of bookshops and libraries are full of books that either speculate about what might have happened if the outcome of these events had been different or use the outcomes themselves as a means of defining the particular character of our country.

An image illustrating a French dragoon forcing a Huguenot to convert to Catholicism, following Louis XIV of France’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and his sanctioning of these intimidating ‘dragonnades’.

Literature and personal stories are full of such moments, too, ‘The Road Not Taken’ by Robert Frost being one of the best known:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

In terms of this country’s relationship with Europe, two roads certainly diverged last June, and continue to do so, and the road we have taken as a country has made all the difference as far as campaigners on either side of the referendum are concerned. But what will the long-term difference be in terms of our attitudes to people born outside the UK? And are there comparable moments in our history where, faced with a stark choice, we took one road rather than another? And (last question for a while), if so, what were the outcomes of those decisions?

The original caption to this cartoon, printed in the wake of the 1905 Aliens Act, has Britannia saying “I can no longer offer shelter to fugitives. England is not a free country.” ©The Jewish Museum

These are some of the questions we plan to explore in a new exhibition called No Turning Back: Seven Migration Moments That Changed Britain, which we hope to open in the autumn of this year in our new space at The Workshop in Lambeth, London. The earliest of these seven moments is 1290, when, under the reign of Edward I, all Jews were banished from England; the most recent (if you can apply that adjective to a future date) is 2020, the date at which it is estimated that mixed-race Britons become the largest minority ethnic grouping. Moments in-between include the Huguenots, the East India Company’s arrival in India, the 1905 Aliens Act, the first scheduled long-haul jet service and Rock against Racism.

We’ve selected these seven moments because they seem to us to define key moments in our history but also because they echo so much of what is happening today. The expulsion of the Jews in 1290 was the only point in our history (so far) when we expelled a whole race or creed – but it has obvious parallels with what is happening today, both in the wake of post-referendum calls to East European residents and others to ‘go back to your own country’ and in the more negative connotations of ‘reclaiming our borders’. The arrival of the Huguenots in 1685 and after is cited as one of the great success stories of immigration – but how different was the reaction then to that mass arrival of foreign labour from the reaction now to today’s migrants, economic or other? And what are the factors that lead to one immigrant being accepted or successful while another is deported or deemed to have ‘failed’ to integrate?[/caption]

The title of our exhibition has since been appropriated by our prime minister and the advocates of a hard Brexit – but actually, when you take the long view of history, for all the defining moments from which there seemed to be no turning back there were a significant number of others when things just happened or changed because of a technological development (such as the availability of affordable, long-haul air transport), or an environmental disaster or because of the human capacity to form attachments. History is nothing if not unpredictable.

One of several blue plaques around the country that mark places associated with Jewish communities before their expulsion in 1290. © noli’s on Flickr

We’re conscious that others will argue that there are seven better moments we could have chosen for our exhibition – and we’d like that discussion to be part of the exhibition. There will be facts and figures, of course, but there will be many more personal stories, ideas and reflections – and we’d like that to be part of the visitor engagement in the exhibition, too. As with everything we’ve done so far, we are planning to enrol the visitor as much as possible in the content of what is on show.

For each of these moments we are already working with a team of academic and artistic advisers, teasing out the human stories of the event and attempting to reveal the consequences of that moment. As with our most recent exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories From Calais and Beyond, this will be a multimedia display with much new material, and with each section involving an interactive element for visitors to engage with.

We would love to hear from you if you:

- • would like to volunteer for the exhibition (or for the project)

- • would just like some more information

If you would like to get in touch, please contact Aditi Anand (aditi@migrationmuseum.org), Sue McAlpine (sue@migrationmuseum.org), Andrew Steeds (andrew@migrationmuseum.org) or Faiza Mahmood (faiza@migrationmuseum.org).

21 October, 2016

We went on a walk last Sunday, along with about 130 others.

It started in the cold, grey and wet, at a time when many of us would still be, if not in bed, certainly doing nothing much more energetic than turning the pages of a Sunday paper and slurping coffee. It ended in glorious early-evening light, with a rainbow over the Serpentine and, if not actual gold at the end of the rainbow, then the next best thing – cakes and prosecco.

Somewhere over the rainbow … Looking east from the Lido café in Hyde Park, the end-point of our Imprints walk. © Faiza Mahmood

It started in Greenwich, where so many migrant stories have started in the past – George I prominently among them, borne to his disembarkation at the Old Royal Naval College aboard the ship Peregrine, but also, though much less regally, Ignatius Sancho, born on a slave ship and later a lobbyist for the abolition of the slave trade. It ended in Hyde Park, just short of the Albert Memorial, flamboyant statue to one of the most-loved migrants of the nineteenth century and the inspiration for the cluster of museums and institutions – Albertopolis – that now draw so many visitors to our capital.

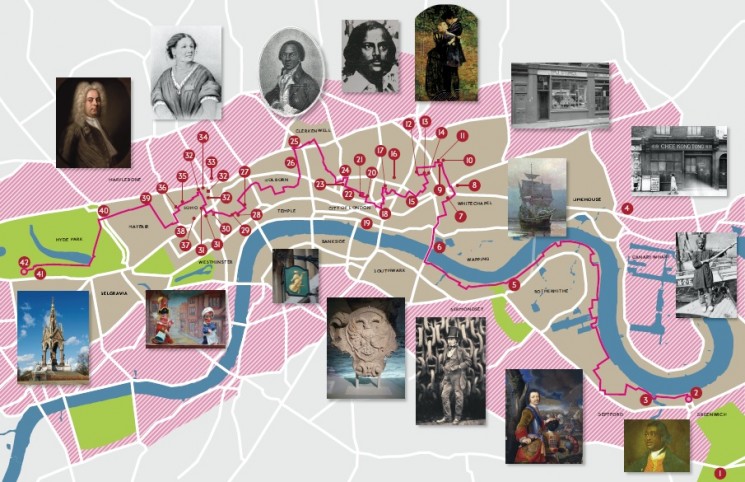

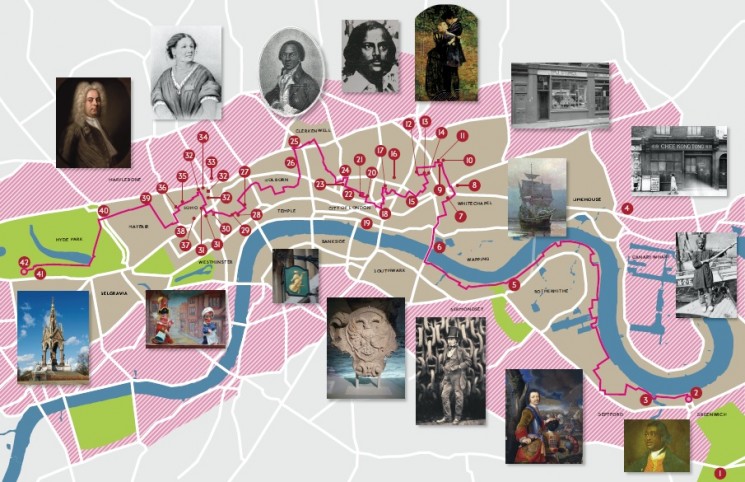

The outline of the route the Imprints walk took through London. © Brandingbygarden

Not all migrants migrate from east to west of the city, of course, but it’s a useful hook to hang an event of this kind on. It’s certainly a long walk, that walk from arrival to establishment, and not all migrants make it with equal success, happiness and good fortune. And it was a long walk, literally, on Sunday, a full 15 miles and counting, which not all participants made with equal success, happiness and comfort of foot. But the overwhelming majority of those who started the walk completed it, and there was a sense of euphoric satisfaction in Hyde Park at the end of the day that may have had something to do with the prosecco on offer, or possibly with the sheer relief of the walk now being at an end – but which was mostly down to the sense of fulfilment and enjoyment of a day spent in good company, learning something about the myriad migration stories that make up the history of London, and of the multiple layers that make each street and region a palimpsest of the migratory experience: whether it’s the Brick Lane Jamme Masjid mosque, in a building that had previously been a synagogue and was, before that, a Huguenot chapel; or the building in Old Jewry, now housing the visa office for the People’s Republic of China but almost eight hundred years previously the site of the first synagogue in this country; or 25 Brook Street, home to George Frideric Handel in the 1700s and the more raucous stomping ground of Jimi Hendrix in the 1960s.

The Jamme Masjid mosque in Brick Lane – previously a synagogue and, before that, a Huguenot chapel. Spectacular minaret sadly not shown. © Aditi Anand

Divided into groups of 10 to 15, each led by an incredibly well-versed volunteer guide and supported by one of our magnificent volunteers, we walked along the south bank of the Thames to Tower Bridge, meandered through the East End, Brick Lane and Spitalfields, wandered through empty and storm-soaked streets in the City, rising again into Clerkenwell and Holborn – passing through the world of clockmakers, jewellers, lawyers and artists, before moving westwards through Covent Garden, Soho, Kensington and Mayfair. In Postman’s Park, Bill Bingham (our very own Ian McKellen) appeared out of nowhere, surprising us with a rendition of Shakespeare’s Thomas More speech (‘Grant them removed, and grant that this your noise / Hath chid down all the majesty of England … ’), delivered (in theory) in the early 1600s to quell riotous discontent at the arrival of the Huguenots. We stopped along the way to hear the story behind particular buildings, or about individuals who had lived in that area, or whole movements of people; and in-between we talked to each other about our own stories, about plans for the Migration Museum Project, about how our country would change in the wake of the recent referendum decisions.

Emily Miller, the MMP’s education manager, in Chinatown with Isabel Morrison. © David Wigram

We liked it so much we are already planning to do it again next year – at least once more in full length, and maybe on a number of other occasions, in a shorter form. And already we’re thinking, if this works so well in London, why wouldn’t it work just as well in any number of other cities: Newcastle, Manchester, Glasgow, Liverpool, Belfast, Bristol, Leicester? Get in touch with us if you want to help us plan how to extend it.

Oh, and we raised hugely important funds for the MMP’s work, too. Our target was to raise £20,000 to enable us to continue delivering exhibitions, events and education work in schools as we build the case for a permanent Migration Museum for Britain. At the time of writing, we are still a little short of our target – the equivalent of finding ourselves in Regent Street, when we need to be in Hyde Park. If you would like to help us reach our target or destination, please go to our MyDonate page.

And, just in case you can’t quite take our word for it, have a look at what some of the walkers had to say about the experience:

Epic day with informed guides – great fun despite the rain!

What a fab day! Like walking through a spread of London’s amazing history!

A wonderful way to explore London and discover how migration is a fundamental part of the city’s identity.

Amazing experience, informative and enlightening. Highly recommend it

I enjoyed seeing so much of London in one go, and learning about all the little histories and significances that would have gone unknown otherwise.

I loved the content and it’s great to have the map as a momento. Lots of highlights that I have been boring my nearest and dearest with: Mayflower pub selling US stamps – Rotherhithe tunnel used to have shops! – De Hems pub history … and of course the wonderful performance in Postman’s Park, a speech which I didn’t know and now love.

Very interesting, and I learned lots! Like the fact that it was easier to be black than Catholic in Tudor England! It made me think about things in a totally new way – I hadn’t thought of Paul Reuter as a German immigrant to London before!

We went on a walk last Sunday. It was a huge success, raising funds and fun in equal measure. Why don’t you come on the next one we organise?

The first Imprints: London Migration Walk took place on Sunday 16 October 2016. Huge thanks to our team of volunteer guides, all of whom were mines of information, wit and inspiration – and to the volunteers who supported them. Without you, this project would be struggling! But the biggest thank you goes to the 130 participants who so good-naturedly and energetically gave up their Sunday to support us on the walk, and did so without complaint, even when the skies emptied their load on us in the early afternoon. Thank you, thank you, thank you. Here’s to the next one!