Talking about Roman migration in 2017

The past is not only a different country; it’s a contested one, too, and nowhere more so than in the extent to which Britain may or may not have been a ‘multi-racial’ society in earlier centuries. As with all debates of this kind, positions quickly become polarised and evidence exaggerated, with each end of the spectrum over-emphasising the historical record to suit its purpose. An example of this phenomenon was witnessed earlier this year, when a BBC cartoon aimed at school children attracted controversy. Hella Eckardt, an academic at the University of Reading whose work was quoted in the ensuing debate, reflects in this blog on both the evidence for a multi-racial Roman presence in this country and the best way of discussing it.

In August 2017, an educational BBC cartoon depicting the story of the son of a black commanding officer on Hadrian’s Wall caused controversy on social media.

A screen shot of the BBC’s “Life in Roman Britain”, with Quintus (right), the son of a Roman commander helping to build Hadrian’s Wall.

The alt-right commentator Paul Joseph Watson attacked the cartoon as a symbol of ‘political correctness’ and ‘rewriting history’, but multiple commentators then pointed out that there is a range of evidence for North Africans in Roman Britain.

The debate widened to consider ethnic diversity in the Roman Empire, and the question of how ‘typical’ long-distance migrants may have been in a province such as Britain. In classic Twitter and infowar style, much of the debate was vitriolic and toxic, clearly indicating that for some commentators the issue was about contemporary political concerns rather than ‘historical truth’. The Cambridge classicist Professor Mary Beard, in particular, wrote a very measured piece about the highly personal and aggressive abuse she received for making the academic case for ethnic diversity.

Reflecting on the controversy a few months on, and writing as one of the academics whose work was cited in the debate, I think it is important to move forward with reasoned debate and informed discussion, rather than aggressive and extreme polemic. It seems to me that there are two main issues: one is about the nature of the historical and archaeological evidence and the other about our ability to communicate these findings, especially when dealing with topics, such as migration or ‘race’, that are politically highly charged.

On the first point it is absolutely incontrovertible that the Roman Empire was characterised by relatively high levels of mobility, and that even in a marginal province such as Britain there would have been contact and interactions between Iron Age communities (themselves of course not uniform) and people from continental Europe, as well as North Africa or the Near East.

The drivers for movement included the Roman army and administration, but also trade and even tourism; in all these cases it would often have been high-status individuals who moved. The flip side of the coin is that the Roman Empire was obviously not a multi-cultural utopia, and conquered populations and slaves were moved against their will.

For Hadrian’s Wall, the place featured in the BBC cartoon, the historical (e.g. accounts of the emperor Septimius Severus, himself from modern Libya, meeting an ‘Ethiopian’) and epigraphic evidence (e.g. inscriptions mentioning officers or units) for an African presence have long been known. More recently, new scientific techniques have added important new information. Isotope analysis examines the chemical signatures preserved in teeth, which essentially reflect the water and food that a person consumed in childhood. The technique is better at excluding local origin than pinpointing specific origins; among the non-locals we can normally only say broadly that an individual came from somewhere cooler or warmer.

The project I led at the University of Reading identified a number of late Roman individuals in Scorton, York and Winchester who appear to originate from cooler areas, such as Germany or Poland, which makes sense, because we know that mercenaries from those areas served in the Roman army.

Another technique measures various aspects of ancient skulls, to establish African or Caucasian ancestry. For example, a 4th-century skeleton from York was identified as the remains of a woman aged 18–23 years, buried with rich grave goods that included both locally available (jet) and exotic (ivory) bracelets as well as an array of other impressive grave goods. Her facial characteristics suggest that she had a mixture of traits common in European (‘white’) and African (‘black’) populations but the results of the isotope analysis are ambiguous – she does not appear to have grown up in North Africa, so may be a second-generation migrant.

Finally, there is DNA analysis, as in the case of the so-called ‘headless Romans’ from York. These were discovered in an unusual cemetery of mainly male individuals, many of whom had been beheaded and some of whom bear injuries from combat. Genome analysis demonstrated that, while most appear to be of broadly ‘British’ descent, one individual may be from the Middle East; he also has an unusual isotope signature.

Reconstruction of the ‘Ivory Bangle Lady’ © Aaron Watson & University of Reading.

All archaeological data have to be interpreted, and it can be difficult to convey the complexities of the material in broad-brush summaries. It is also almost impossible to quantify numbers of incomers – especially given that scientific analysis has so far largely focused on unusual burials, thus potentially skewing the impression we form. While many of the right-wing commentators are focusing on ‘race’ in terms of skin colour, in the Roman world ethnicity was viewed quite differently: factors such as language (did the individual speak Latin or Greek well?), education, wealth, kinship and place of origin were probably more important. Archaeology and the reconstructions of the past we create are characterised by uncertainties, but conveying those complexities adds to our interpretation and allows us to challenge our own preconceptions. It is especially important that school children, who in Britain cover ‘the Romans’ at Key Stage 2, learn that the Roman Empire was not homogenous, but characterised by the interplay of locals and newcomers in wonderfully complex ways.

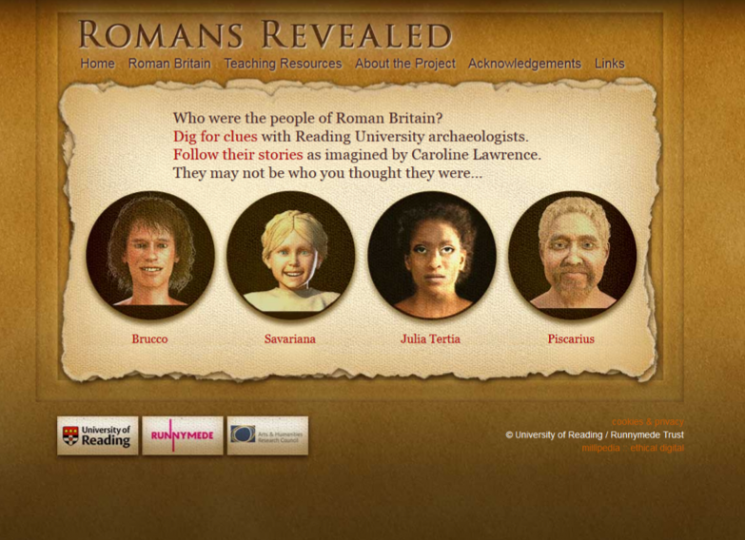

To convey these latest scientific findings, I have worked with the Runnymede Trust to create a website and learning resource for Key Stage 2 and the Ivory Bangle Lady also features in a new website about the history of migration in Britain aimed at older pupils.

Educational website on Romano-British diversity (http://www.romansrevealed.com/).

In conclusion, while contemporary concerns will inevitably shape what questions we ask of the past, it is clearly wrong to expect straightforward validation for current political points from archaeological evidence. What archaeology can do is to provide an increasingly rich and complicated picture of life, which we as a society can compare and contrast with other societies and different time periods.

Hella Eckardt teaches provincial Roman archaeology and material culture studies at the University of Reading. Her research focuses on theoretical approaches to the material culture of the north-western provinces, and she is particularly interested in the relationship between the consumption of Roman objects and the expression of social and cultural identities.