Racist politics and human rights

A guest blog by Anthony Lester, distinguished friend of the Migration Museum Project, Liberal Democrat peer and author of a new book on the threat to our freedom.

Politicians are all too easily tempted to exploit racism in their pursuit of power. It is a dangerously divisive tactic that plays on religion, nationalism and xenophobia, as we see in the seething cauldron of British politics today.

In 1968, to its shame, Parliament surrendered to racism. The newly independent East African governments had introduced racist policies of ‘Africanisation’. They gave preference to their own citizens in trade and employment and required British Asians to leave. British Asians came to Britain in increasing numbers as British citizens with full British passports.

Two Conservative MPs, Duncan Sandys and Enoch Powell, campaigned to take away the right of these British Asians to settle in Britain. They exploited public prejudice against non-white immigration. The Home Secretary, Jim Callaghan, gave in. He rushed an emergency Bill through all its Parliamentary stages in three frantic days and nights. British citizens who had not been born in the UK, or whose parents or grandparents had not been born here, were stripped of their right to safe haven in Britain. On its face, the Bill was not racially motivated. But its intention was racist and so was its effect.

Chaos at Nairobi airport, Kenya, 1968, with barriers closed against Kenyan Asians attempting to leave the country as the new UK legislation restricts entry.

Some 200 000 British Asians lost their right to enter and live in their country of citizenship. They were divided from their families in Britain, imprisoned if they tried to enter without Home Office permission, or shuttled across Europe, Africa and Asia, desperately seeking a new world.

Ministers misused their majority in Parliament to abridge the basic rights of a vulnerable group of fellow British citizens because of their colour and ethnic origins. It was a classic example of what J S Mill termed ‘the tyranny of the majority’. The British Asians had no means of seeking redress from British courts because the Westminster Parliament was all-powerful. Until the Human Rights Act came into force in 2000, British courts could not declare the 1968 Act incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. So test cases were taken to the European Commission of Human Rights, and I led the legal team.

Europe came to the rescue. The Commission rejected the government’s case. It decided that the 1968 Act was racially motivated and that it had subjected British Asians to inherently degrading treatment.

Roy Jenkins, who had replaced Callaghan at the Home Office, accepted the damning verdict, and the British Asians came and settled here. Many made their homes in Leicester. They, their children and grandchildren made, and continue to make, an outstanding contribution to that city and to our nation.

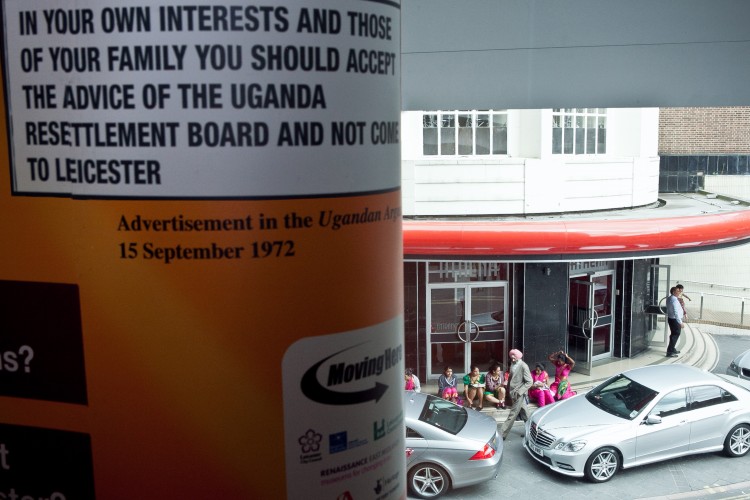

Despite this kind of advertisement, placed in the Ugandan Argos in 1972, thousands of Ugandan Asians came to settle in Leicester, a city whose fortunes they have helped to transform. ©Kajal Nisha Patel

What became known as the East African Asians’ case convinced me of the need for a British Bill of Rights protecting everyone against the misuse of power. Thirty years later the Human Rights Act was passed, which enabled our courts to give effective remedies, including declarations that Acts of Parliament were in breach of European Convention rights.

The Human Rights Act is now under threat and needs your support. I hope that my book – Five Ideas to Fight For – will encourage you to do so.

Anthony Lester is a human rights lawyer and a Liberal Democrat Peer and a frequent commentator on legal matters. His book Five Ideas to Fight For: How Our Freedom is Under Threat and Why it Matters is published by Oneworld Publications and is available now from Amazon and other booksellers.