Being a young interpreter

In the third of our series reflecting on the experience of running workshops with young people and schoolchildren, Sarah Crafter (The Open University) and Humera Iqbal (University College London) talk about a project that has as its focus young people and children who act as interpreters for their parents and families – and how this focus can enhance the empathetic understanding of pupils (the vast majority) who are not migrants themselves.

Animation and image by Alan Fentiman: http://bit.ly/2aVfHYw

‘When I was small and I moved in Milan, I used to live with my parents and uncles. I have really good memories with them until the age of 12. Unfortunately, I had to move to the UK, and they couldn’t come. This event changed me and the way I act.’ Safi, aged 15, (Bangladesh, Italy, UK)

Safi, aged 15, moved to Britain three years ago from Italy, having previously lived in Bangladesh. His childhood had been full of instances of resettlement. When young people, like Safi, migrate to a new country, they can often be left with a sense of loss: for people left behind and places they loved. At the same time, they can face new challenges in their new setting; getting to know new people, learning the language, culture, systems and structures in the new country.

We explored some of these themes at the workshop we ran in 2016 for the Migration Museum Project with a group of 65 local schoolchildren at their exhibition Call Me by My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond. For quite some time we have been working with children and young people who have migrated with their families to a new setting in which they act as child language brokers – children and young people who interpret and translate for family and friends who can’t speak English. Over the years we have learnt that young people translate across lots of different situations and places like doctor’s surgeries, schools, banks, shops and workplaces. Sometimes they really enjoy being a young translator and take great pride in being able to help their families and friends. In other instances the conversations are difficult and people are not always very sympathetic. Many of the young people we speak to tell us, just as Safi did, how difficult it was to arrive in a new country and not be able to understand what people were saying. This sense of change and loss was also explored in the Call Me By My Name exhibition in relation to refugees, and we were able to identify many similarities between the exhibition and our research.

We built on some of these themes in the workshop. We asked the pupils to think about what it feels like to migrate, to be in a new place, to go into the unknown and to learn to communicate when there is no shared language. We started by showing a short animation from our research which features the voices of young people speaking about arriving in a new place and translating.

After watching the film, the young people gathered into groups to talk about some of the main themes that had arisen. This was quite a difficult task for some people, especially if they hadn’t experienced or thought about what it might mean to be a young translator or to migrate to a new country.

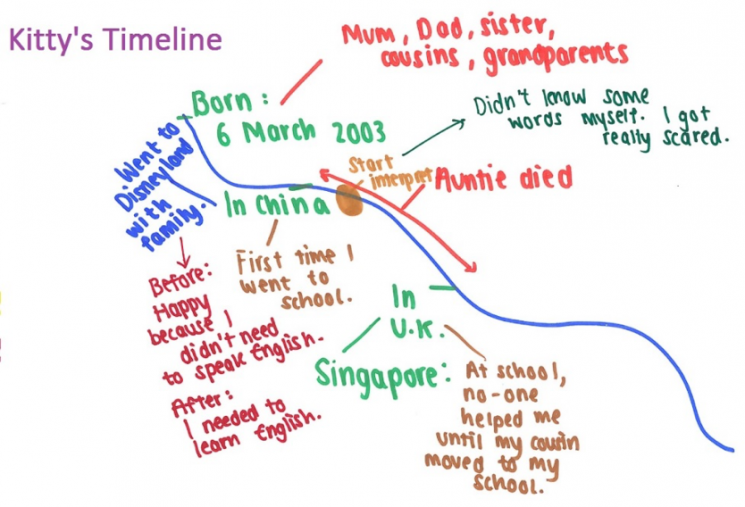

Yet, in truth, most of us can pinpoint a situation or feeling of being ‘out of place’ or alone, or unable to say what is in our minds. We wanted everyone to be able to capture that feeling and, to do that, we asked the pupils to put together a timeline map of their own experiences (working with timelines being something we have done in our research). We showed a timeline map made by a teenager called Kitty, who had migrated from Hong Kong to the UK with her family. It captured many markers of upheaval as well as instances of emotional change in different stages of Kitty’s life.

Using Kitty’s narrative as inspiration, the workshop pupils were asked to draw their own timeline, starting with the places they had lived or the places they had moved to (a house, a street, a country). The pupils then added people in their ‘migration timeline’ to get a sense of those who are always with us, those who come into our lives and those who fade out. Languages learnt and spoken were added. The pupils were encouraged to describe any ‘firsts’ they had experienced, such as the first time riding a bike, trying a particular food, reading something that made them cry.

This workshop was useful for the pupils because it enabled those who had never migrated to a new country, or learnt a new language, to gain a greater depth of empathy and understanding about how this must feel. In loading memories of newness, change, experience and important relationships, the pupils were encouraged to explore what their own feelings might be in moving to a new country and learning a new language. Our workshop also helped those pupils who had migrated, and who did speak a second language, to talk freely about their experience with their friends. We were impressed with how bravely they spoke to us, and their friends, about what that felt like for them. Teachers might also use similar exercises or prompts within school during citizenship and personal health and healthcare lessons, to explore issues of diversity.

You can find more information about our project here.

Dr Sarah Crafter is a senior lecturer in the Department of Psychology at the Open University in the UK. She has a PhD in Cultural Psychology and Human Development and is interested in cultural identity development and ‘non-normative’ childhoods. Her work with child language brokers grew out of broader interest in the constructions or representations of childhood in culturally diverse settings. Dr Humera Iqbal is a lecturer in psychology at the Department of Social Science at University College London. She is interested in identity and the migration experiences of families and young people, in particular how they engage with institutions in new settings. She is also interested in mental health and wellbeing in young people, particularly those from minority groups. Her research uses mixed methods as well as arts- and film-based methods.