Archives

8 June, 2016

This guest blog is written by Rob Pinney, one of the photographers who submitted photos for our exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond, which is at 28 Redchurch Road, London, until 22 June (details here). Rob’s book, The Jungle, is on sale at the exhibition and from his website (see below) with all profits going to charities working in Calais.

A complex relationship in a complex place

Grocery Store, November 2015. Shops like this provide, among other things, basic food staples and mobile phone credit top-ups, incredibly important for keeping in touch with family both at home and often at different stages of the refugee ‘trail’ through Europe. Many people in the ‘Jungle’ report having been victimised and attacked by both the police and ordinary citizens when outside the camp, and so feel unsafe walking into Calais to use local shops. This particular shop was destroyed in March 2016 as part of the eviction and demolition of the southern half of the camp. © Rob Pinney

As the main point of departure for sea and rail travel to Britain, the coastal town of Calais in northern France has become a ‘hotspot’ for asylum seekers hoping to build a new life in the United Kingdom.

‘The Jungle’ — the term used to refer to the shanty town settlements that have become synonymous with Calais — has no fixed location. But it is most commonly associated with a former landfill site not far from the ferry port that at its peak during the 2015 refugee crisis held a population of some 8,000 people.

The political discourse around the jungle and those temporarily seeking shelter there thrives on generalisations. Labelled a ‘swarm’ and a ‘bunch of migrants’ by British Prime Minister David Cameron, in the eyes of many the people here are not individuals but a collective mass — the object of a confused war of words: ‘refugees’, ‘asylum seekers’, ‘economic migrants’.

The reality is far more complicated. Many have fled war and political persecution. Others, notably from Afghanistan and Iran, left to avoid being made to fight for a cause they did not believe in. Many will show you photographs on their mobile phones of family already living in the United Kingdom, whom they hope to join. And some have spent years, occasionally decades, living and working in the UK, only to find themselves suddenly ejected. For them, the journey is not one of migration but a return home.

‘What is it like?’, often asked, is a simple question that defies an equally straightforward answer. Unlike the epic photographs of Zaatari in Jordan, whose orderly lines of identical shelters extend outwards on a vast scale, the Jungle follows no such logic. The Jungle is a city. Alongside countless tents and shelters, nestled into any and all available space with little regard to order, stand shops, cafes, restaurants, hairdressers. While different nationalities have generally grouped themselves together — as is common in any city — these lines are also frequently transgressed by a shared political precarity that unites its citizens. But above all, the Jungle is a city that is constantly changing. Some of these changes are internal and organic, but others have been the result of more profound changes in the political landscape in which the Jungle is deeply embedded, and yet over which it holds no control.

While cameras are a common sight, they are treated with great suspicion. Many people are wary of being photographed: some fear it may endanger their families should news of their escape reach home; others worry that evidence of their presence in France may be used against them should they eventually claim asylum in Britain; and others still feel ashamed of the situation they now find themselves in and do not want it immortalised in any resulting pictures.

It is not difficult to create photographs that evoke misery and suffering in the Jungle. And while such pictures might fit with what we think documentary photography ought to look like, such images usually take recourse to particular visual tropes and do little to deepen public understanding of a complex place at a time when greater understanding is so sorely needed. At the same time, it would be wrong to beautify what remains an utterly deplorable situation that exists not out of necessity but because of broken politics.

The photographs presented here are drawn from a much larger collection that spans four trips over six months. This selection is tempered by conversations I have had with some of those who live there about photography and the representation of the Jungle in the media. One friend from Darfur lamented the way in which many photographers came simply to ‘make their own business’. While I hope that the time I have spent volunteering on each of these trips is sufficient in his eyes to keep me out of this category, I also hope that the images here are seen as ones that are sensitive and respectful towards the issues so frequently voiced by the Jungle’s people. There are no portraits, nor any identifiable faces. In their place, I have tried to show traces of the many lives that are now collectively on hold. The impression left may be one of a desolate, depopulated landscape. But the reality couldn’t be further from that: beyond the edges of each frame is a vibrant and dynamic city in the making.

Police Lines, March 2016. Eritrean men watch through police lines as their shelters are destroyed. Following the partial eviction that took place in January 2016, the authorities announced a more significant intervention two months later: the southern half of the camp was to be evicted and demolished. They estimated that this area contained 800–1,000 people, but a census conducted by charities working in the camp suggested the figure was as high as 3,500. Many of those who lost their homes chose to leave the ‘Jungle’ and retrace their steps, often heading back to Germany, where asylum policy is thought to be more lenient. But many others moved into the little remaining space in the northern half of the camp, condensing those from different communities ever closer together. © Rob Pinney

Mario’s, November 2015. Mario’s is one of a number of restaurants that used to line the mud road running through the southern half of the camp. Many of the owners were formerly child asylum seekers who had been granted leave to remain in the United Kingdom but who had to leave upon turning 18 years old. Many now have asylum in France and, in some cases, Italy, but continue to run their businesses in the ‘Jungle’. Mario, who owned the 3 Star Hotel, was given his name on account of his impressive moustache. The hotel was among the hundreds of makeshift restaurants, businesses and homes that were destroyed as part of the eviction and demolition of the southern half of the camp in March 2016. Since then, and as the number of newcomers has started to increase once more, many of the remaining restaurants have opened their doors to people hoping to avoid the bitter cold of a night spent in a tent. © Rob Pinney

Burning Shelter, March 2016. As the eviction of the southern half of the ‘Jungle’ gathered pace, fires set by refugees and the use of tear gas by French riot police became commonplace. In the UK, the media have woven the persistence of fires into a narrative of destruction and lawlessness. But you might also see it this way: the decision to put a match to the walls of their shelters is arguably the only way refugees were able to exert at least a degree of agency over the inevitable destruction of their homes. © Rob Pinney

Shipping Container, January 2016. In January 2016, French authorities announced that they were going to clear a 100-metre ‘buffer zone’ between the edge of the camp and the adjacent motorway, which leads to the ferry port. At the time, charities working on the ground estimated that this would mean the displacement of more than 1,000 people. It was suggested that at least some of the displaced could move into these newly built converted shipping containers. Among residents of the ‘Jungle’, the reaction to the new containers – presented generally in the British media as a generous gesture – was decidedly mixed. Although they offered a warm and dry place to sleep for 1,500 people, the fear was that the registration information and biometric data that were gathered as the condition of a place (entry is granted by a handprint scanner) might be used against any refugee reaching Britain and making an eventual asylum claim under the Dublin Regulation. More generally, many also felt that by moving into the new containers they would isolate themselves from family, friends and the broader social environment of the camp. One resident described the containers as being ‘like a prison camp’. © Rob Pinney

Cricket in Afghan Square, January 2016. Although still bitterly cold, this was the first full day of sunshine after several weeks of rain, during what was for many refugees their first experience of a northern European winter. Under these conditions, once clothes become wet, they are almost impossible to dry out again – so many refugees made full use of this momentary shift in the weather to get out and play. The shipping container in the background houses a small fire engine, built and funded by volunteers from the United Kingdom and operated by a small crew of trained refugees. © Rob Pinney

Rob Pinney is a documentary photographer and researcher with a particular interest in war, post-conflict, displacement and migration issues. His project in Calais is ongoing, a portion of which is now available as a book, The Jungle, available at Call Me By My Name. To see the full series, visit his website. His Twitter handle is @robpinney and his Instagram account is @rob.pinney.

2 June, 2016

As a way of setting the scene to our newest exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond, Professor Robert Tombs has written this historical account of the city and its enduring importance on both sides of the Channel.

Burghers and roast beef

The bit of the continent closest to England has always been hugely important to us islanders – so much so that, for more than 200 years, it was actually part of England.

During the long medieval wars between France and England, it was besieged and captured by Edward III in 1347. When the town surrendered, 12 burghers were threatened with hanging by Edward, but spared by his Queen Philippa – a drama immortalised by the sculptor Auguste Rodin in a sculpture now displayed next to the Palace of Westminster.

The Siege of Calais, 1346–47. Artist unknown.

Edward expelled its native population, and made Calais into an English trading post and military and naval base, with thousands of merchants handling England’s greatest export to the Continent – wool. Dick Whittington was its mayor in 1407. It was represented in parliament, and its profits provided up to a third of England’s tax revenue. Its sizeable hinterland included Sangatte, and it was strongly fortified and defended by a large professional garrison.

In the 1450s, it was commanded by the Earl of Warwick, ‘the Kingmaker’, and this enabled him to play a crucial role in the Wars of the Roses. However, Calais’ trade declined, its defences crumbled, and when it was captured by surprise by the French in 1558, it was important only as a blow to the prestige and popularity of the Queen, Mary Tudor, who famously said that ‘Calais’ was written on her heart.

In later centuries, the story was rather one of tourism. Calais was where the English had their first taste of the Continent. William Hogarth’s satirical 1748 painting, O the Roast Beef of Old England (‘The Gate of Calais’), now on display at Tate Britain, showed the contrast as patriotic Brits like himself saw it: between free and prosperous Britain and poor and down-trodden France.

‘O the Roast Beef of Old England (The Gate of Calais)’ by William Hogarth: Tate Britain.

In the 18th century, Calais’ famous Hôtel de l’Angleterre – with its own theatre and carriage hire – was said to be the finest in Europe. Calais was also a place of refuge for those islanders who had blotted their copy book at home. There were so many British residents in the 19th century that it had its own English-language newspaper.

As early as 1802, a plan had been put forward to build a Channel tunnel, and in the early 1880s work actually began at both Sangatte and Dover, and pushed a couple of miles under the sea. But the War Office feared it might be used to launch a surprise invasion, and put a stop to it. After the First World War, the prime minister, David Lloyd George, told the French that he would build a tunnel so that Britain could send aid to the French if they were again attacked, but once more the War Office vetoed it. In 1940, a British garrison defended Calais bravely until overwhelmed by the invading Germans.

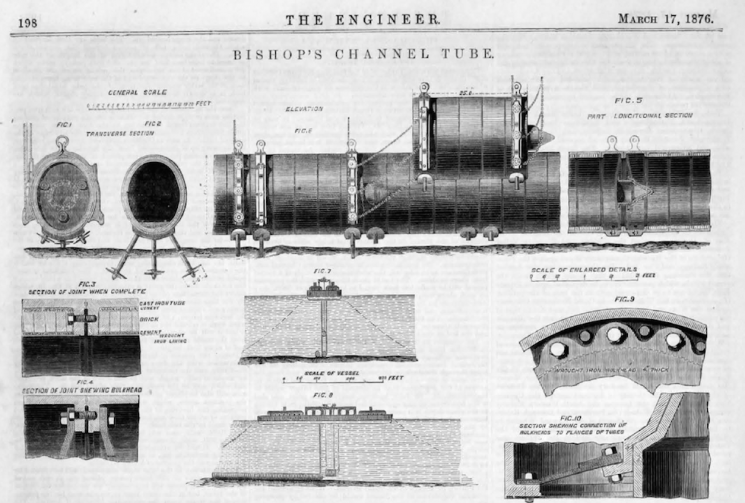

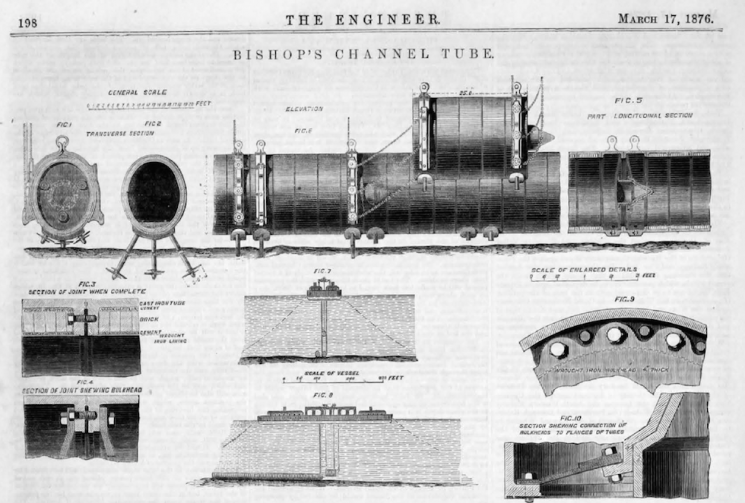

Paul J Bishop’s Channel Tunnel Tube, designed in the 1870s, was designed to sit on top of the seabed rather than boring beneath it.

Always one of the main gateways from England to the Continent, its role as a seaport was of course transformed by the building of the Channel Tunnel, which opened in 1994 after more than a century of false starts.

Calais today has become notorious for another reason: for centuries the route by which the British came to Europe, it has now become a symbol of the desperate efforts of refugees and migrants to leave Europe in the hope of economic opportunity in Britain.

Inside a squat in a former factory, Calais. The factory has since been evacuated. © 2015 Christian Sinibaldi

But this is not the first time that Calais has been an escape route. Many French Protestant Huguenots passed through it in the 1680s, and then a century later came thousands of refugees from the French revolutionary Reign of Terror. Successive waves of asylum seekers, including kings and prime ministers, took the same route. In 1848, British workers attacked by xenophobic revolutionary mobs had to take refuge on Channel ferries.

As long as there are people who, for whatever reason, seek shelter in Britain, Calais will be the primary port of call.

Professor Robert Tombs, lecturer in modern European history at St John’s College, Cambridge, and author of The English and their History, will be appearing in our panel discussion on ‘What is Britishness?’ at our Call Me By My Name exhibition (Londonewcastle Project Space, 28 Redchurch Street, Shoreditch, London E2 7DP) on Tuesday 14 June, 7–9pm.

5 May, 2016

Adam Woodhall visited the migrant camp in Calais in November 2015. In the conversations that followed (particularly one with the MMP’s Sue McAlpine, who is curating Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and beyond, shortly to open in Shoreditch, London), he realised that his personal interest in environmental issues, especially drought caused by climate change, was intimately linked to the stories of some of the people in the Calais camp.

So here I am, six months after my visit to Calais, happily tapping away on my laptop, in my comfy, warm, dry, safe, settled flat in London, looking through my double-glazed windows onto a calm residential scene. In Calais I had looked into the eyes of people whose journeys I could only dimly envisage. They’d travelled across continents, through war zones, leaving behind family, friends, treasured possessions, hopes and dreams. Here they were now, standing in a puddle, with only the clothes on their back and a dream of safety and a better life in the UK.

The migrant camp at Calais. ©Adam Woodall

What was it that kept them here, waiting for fate to finally smile on them? In conversations throughout the UK, whether it be in pubs, coffee shops, on Twitter or in the media, there are many views on this: they were there to ‘take our jobs’, to ‘exploit our benefits’ or, more benignly, to be re-united with family members who were already legally in the UK.

Whatever truth there may be in these views, it is only one part of the story of why these individuals find themselves in a cold, wet, miserable migrant camp in Western Europe. There is context, stretching back a decade or more, to the situation they find themselves in – and a significant factor in the narrative of the migrants is their own local environmental crisis. The story of these people goes way back to their birthplace. To a time when they too would look out of their window from their comfortable and dry home, feeling happy, safe and content.

For some of them the view they looked out upon would be very different from mine. In my mind’s eye, I see them looking out upon a rural landscape, in a wide Syrian valley. There are fields beyond their village, some with crops, some with animals grazing. The weather is hot, there are children playing and the elders are sitting out on shaded verandas.

This is 2006, and something is starting which will change their lives forever. What is starting is an extreme and long-term drought, which in some areas of Syria led to 75 per cent of households* suffering total crop failure. Imagine your local Asda, Sainsbury, Tesco and Morrison’s shutting down, leaving only the occasional corner shop open, and all employment opportunities drying up at the same time. Would you stick around? Or would you move to where there might be some food?

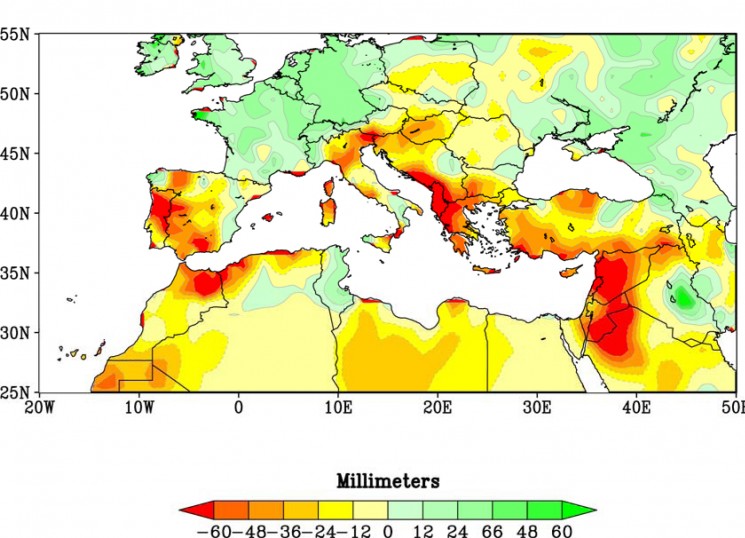

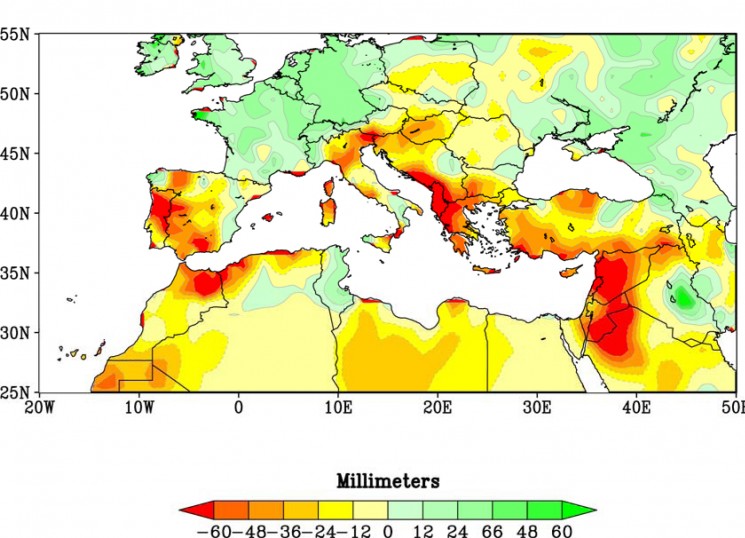

A chart showing the increased frequency of drought in the Mediterranean area (Hoerling, M, J Eischeid, J Perlwitz, X Quan, T Zhang, and P Pegion (2012) ‘On the Increased Frequency of Mediterranean Drought’ in J. Climate, 25, 2146–2161; first shown on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration website in 2011). Reds and oranges highlight lands around the Mediterranean that experienced significantly drier winters during 1971–2010 than the comparison period of 1902–2010.

For these people, the first step of this journey was having to admit to themselves that living in the place where they had grown up, as had generations before them, was no longer viable. So they moved to a Syrian city where food was more readily available. This unfortunately proved to be out of the frying pan of long-term drought and into the fire of a failing state, with threat multipliers – such as ISIS, the corrupt Assad regime, refugees from the Iraq conflict – all conspiring to light the touch paper of violent protest and then blowing up into a full-scale civil war.

An aerial view of the Za’atri refugee camp in Jordan, whose population was estimated at 83,000 in March 2015. Estimates for the population of the migrant camp in Calais are between 3,500 and 5,500 people.

So they move again, this time to Turkey, where they join millions of other Syrians in refugee camps. Here they hear of how things are better in Europe, so they decide to use some of their savings to make the risky Mediterranean crossing to Greece. Arriving in Greece, they find out that a family member is in the UK, and so they decide to trek across the continent to get there.

Ten years after the drought starts in Syria, here they are standing in a puddle in Calais, being looked at by me. My story ends with me getting back on a ferry and into my own bed before midnight. Their stories continue to be clear as the mud in that puddle.

* This figure is taken from Erian W, B Kaplan and O Babah (2010) Drought Vulnerability in the Arab Region: Special Case Study, Syria, p.15, para 3. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction.

Adam Woodhall works with individuals and organisations to help them be environmentally, socially and financially sustainable. He is the author of the book Empower Change and is particularly focused on engaging people to change behaviours. Adam has also just launched a ‘sustainable’ comedy career. His Twitter feed is @adamwoodhall

17 March, 2016

Last autumn, at a time when we were working with the National Maritime Museum on a residency exploring the theme of migration, the Museums Journal contacted us for our thoughts on the migration crisis for a piece that eventually appeared in its October edition.

Most museums plan their activity years in advance, so it can often be challenging for them to react when the focus of either their museum or their exhibition suddenly becomes front-page news. But the Migration Museum Project is a museum in search of a home and therefore able to react more nimbly than this. Our position is complicated, however, by the fact that we’re a heritage museum, with an ambition to tell the long story of migration into and out of this country; we are not a campaigning political organisation.

How then should we react to the stories of hundreds of thousands of people forced to leave their countries in search of safety and a better life?

One of a series of photographs taken by Chris Barrett, who visited the migrant camp in Calais twice on behalf of the Migration Museum Project. © Chris Barrett

How we do this in the physical space we hope to inhabit in the not-too-distant future will doubtless give our curators and designers a long line of sleepless nights. In the interim, though, we have run a number of blogs that have clearly been influenced by the current migrant crisis, even if that hasn’t been their main focus. Our principle here, as elsewhere, has been that how we understand the past affects the way we behave in the present, and that we think differently about current crises – and act differently, too – when we see them as part of a general pattern of human movement into and out of countries in search of safety, stability and better prospects.

© Chris Barrett

But talk is talk, and we have also planned a programme of activities that focuses centrally on current migration developments. We are planning an exhibition in June – a momentous month that sees both the referendum and Refugee Week – exploring the complexity and human stories behind the current refugee ‘crisis’ with a particular focus on the refugee camp in Calais. The exhibition will take place in the Londonewcastle Project Space in Shoreditch, London, and will be an immersive storytelling experience with work across visual art, photography, film, sound and performance. A significant group of established and emerging artists, some refugees and migrants themselves, some even camp residents, will show their artistic response to the Calais camp.

The exhibition will provide a backdrop for a wider programme of performances, talks, workshops and skills and shared learning sessions – as well as an education programme that will include workshops co-delivered with a young person who has experienced forced migration, and performances by students participating in our theatre-in-education programme.

© Chris Barrett

Anyone interested in working with us on this venture, or wanting to contribute funds to it, should get in touch with Sue McAlpine or Aditi Anand, who are curating our residency. We will keep you updated with developments, particularly in the area of funding, and give you full details of the dates and the programme of activities nearer the time.

The photographs featured on this post were taken by Chris Barrett in Calais. Chris’s photos, as well as those of many other photographers we have worked with, will be part of the display in June.