Stepping up: The role of education in responding to the riots

In the wake of the riots, our learning team, along with two classroom teachers, reflect on the importance of teaching migration to counter dangerous and divisive narratives.

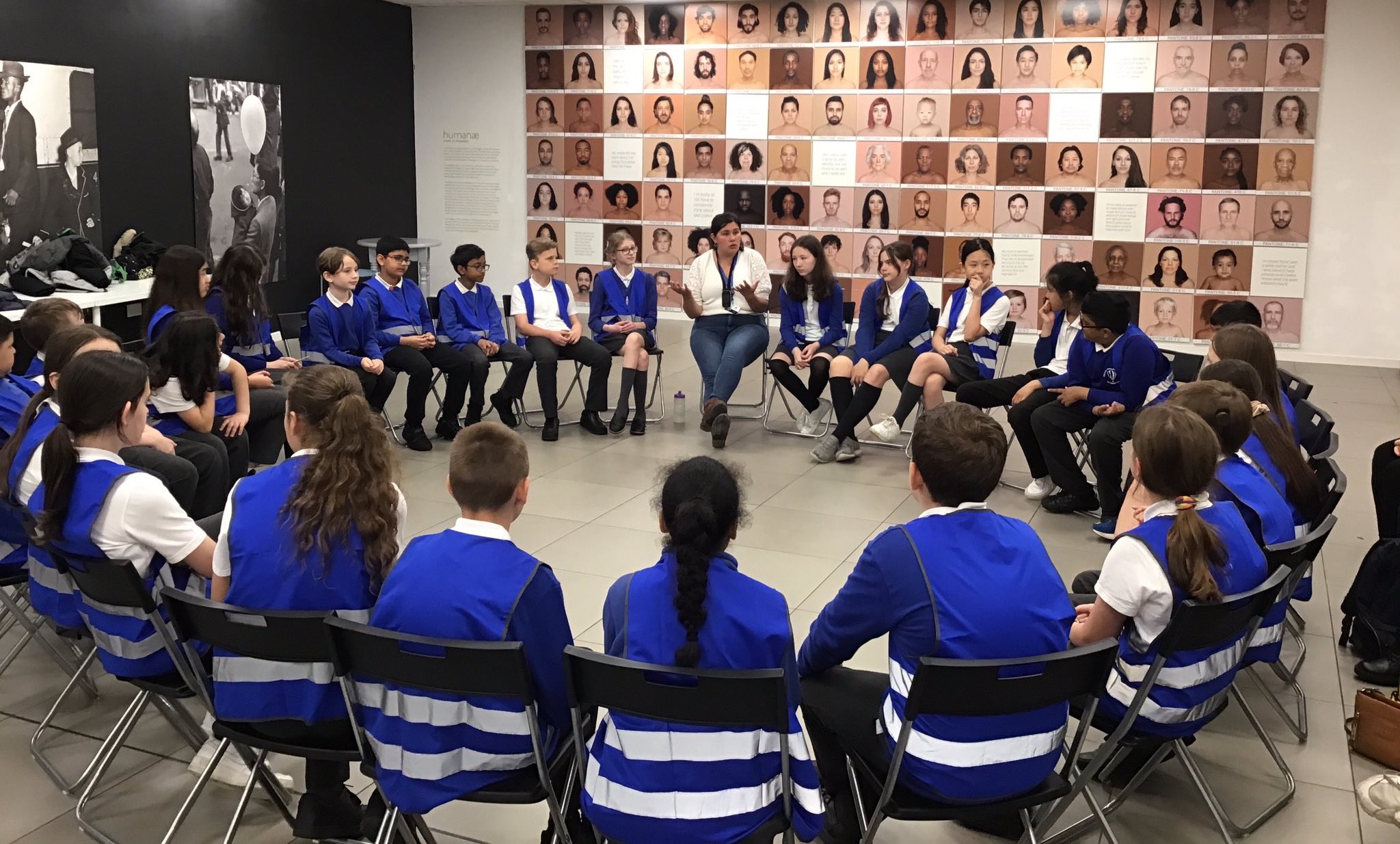

The Migration Museum’s Learning Officer Tia Shah facilitates a school visit with a class from Pelham Primary School (Image: Pelham Primary School)

The riots that swept across the UK last month show that there is so much work to be done to bridge divides and contribute to a society that feels more connected to each other. As an organisation which aims to create spaces where people can come together to explore migration and share stories, we are committed to playing our part in challenging dangerous and divisive narratives.

As racist violence erupted onto our streets, we happened to be installing a powerful piece by Liz Gerard, entitled Chart of Shame, for our upcoming exhibition, All Our Stories: Migration and the Making of Britain, opening to the public on 12 September 2024.

The work, a giant bar-chart of newspaper front pages taken from 2016, was originally displayed in our No Turning Back exhibition. This piece demonstrates how the overwhelmingly negative and sensationalist way that our media covers the topic of migration can play a dangerous role in depicting migrants in a certain light. We knew that the work would still be highly relevant for our upcoming exhibition – but did not realise just how pertinent it would be.

Installing Chart of Shame by Liz Gerard – in 2017 (l) and in 2024 (r)

We have released a statement reflecting on the riots, and hope that we can continue countering bias and misinformation through our work at the Migration Museum – especially through our learning programmes.

Engaging people in stories of migration is a key way to explore our shared heritage, understand what connects us, and unpick the legacies of Britain’s colonial past. Storytelling is a vital way to undo and unlearn prejudices, and our work at the museum encourages meaningful and courageous conversations.

We know that by providing space for young people to engage in these topics, they develop a better understanding of the world around them, their place within it, and are better equipped to engage critically in discourse around migration, belonging, identity and race – whether in the playground, at home or on social media. There is huge importance in teaching migration and intersecting themes. Now more than ever, it is our role to initiate dialogue and foster a sense of belonging – in the classroom and beyond.

Pairing storytelling with key facts about migration can be hugely effective, especially seeing as the reality of migration is in stark contrast to the inflammatory headlines, social media content and rhetoric in parliament.

Britain takes just 1% of the world’s refugees, and refugees make up just 0.54% of our population. We deny asylum seekers the right to work, while only offering £49 per week to live off for those in non-catered accommodation1. Asylum hotels are stripped of all amenities and beds are added to the rooms – so people are far from living a life of luxury on taxpayer’s money.

It is also a fact that the largest migrant groups in the UK aren’t refugees or asylum seekers, but students and professionals. Immigrants are much more likely to start their own businesses, contributing billions of pounds to the UK economy, while of the UK’s 100 fastest-growing companies, 39 have a foreign-born founder or co-founder. Classrooms are a place where these facts can be digested, countering the negative bias we see elsewhere.

Complicated views around migration are often layered with racial bias. The riots were not just an attack on immigration, but on people of colour and Muslims. These were race riots – and therefore it is essential to address the systemic racism that underpins many people’s notions of Britishness and British identity. For many of those that took to the streets to spread violence, Britishness means whiteness.

Racist views tied to notions of Britishness are incredibly dangerous, but can be countered. Teaching about migration is an essential way to do so; migration histories show us that there is no static, singular identity that can summarise these islands’ peoples. Our identities have always – and will always – be shaped by the comings and goings of people. Teaching migration in its entirety means stepping away from myth-building tropes, exploring what connects us, platforming new voices and, sometimes, sitting in discomfort.

As we prepare to launch our upcoming exhibition, we are busy creating a range of resources and learning materials that will engage learners in the stories and themes of migration. We’ve worked with two Teach First secondary school teachers, who joined us over the summer for internships, to develop resources around media literacy, English and critical thinking.

As teachers return to school, we wanted to share their thoughts and advice on how best to approach the new term in the wake of the riots.

Sarah Dualeh, a secondary-school English teacher:

“As an early-career secondary school teacher, I quickly became aware of the lack of training that teachers receive to raise or answer difficult questions in the classroom. We are told to remain apolitical. We are told to avoid social and political commentary. Yet, we are expected to shape and challenge younger generations. Teaching is not simply about ensuring that your pupils are fit for the workplace, it is also our role to ensure that our students are morally and socially equipped for society.

It will be an unpredictable start for many teachers re-entering the classroom this month. I was in Liverpool during the riots, and had the opportunity to speak to a Liverpudlian who shared that his 16-year-old mixed-race niece had not left the house in a week due to fear that she would be racially abused. At that moment, I reflected on my pupils and whether they were in a similarly precarious situation to this young girl. It became clear to me that this was not simply a reaction to immigration, but a riot against the diversity of Britain itself.

I felt that it was my responsibility to tackle these subjects and address them in my classroom. Not only are we teachers returning to students who were affected by the violence, but also students who had the potential to be perpetrators – a 12 year old boy was among those charged for being involved in the riots.

Educators can ignite change by being at the forefront of tackling myths, providing counter-evidence and equipping our children and young people with the tools to recognise and challenge racist, xenophobic narratives and policies. What I ask of us, as educators, is to have those difficult conversations, continue to push to diversify the curriculum, and embed values of inclusion and celebration of difference in the classroom.

The conversations that may make you, the teacher, feel uncomfortable are always the most crucial. We must find the balance between the pedagogical aspect of our work and not imposing our political opinions on our pupils. Instead, we should be supporting them to have the confidence to shape and share their own informed opinions.

As we return to our classrooms, teachers may feel anxious or unequipped to deal with the events that happened over the summer. If you do, remember that there is support available via the Employee Assistance Programme, which assists with counselling and life management. You can tap into available networks, check-in with colleagues, and look out for Continuing Professional Development (CPD) courses.

Our priority is to establish a safe and protective environment for students. This can happen if we, as educators, reimagine and hone our teaching practices so that they meet the urgency of our current political moment.”

Helen Ferris, a secondary-school English teacher:

“When I started teaching secondary English, I would panic when students would ask difficult questions. I was aware of the requirement to provide an answer that did not reveal my personal or political beliefs and I didn’t want to act as an authority on issues I was unqualified to speak about.

Studying English raises lots of questions. I’ve learned over the course of my career that sometimes asking the question is the point. Some answers are hard to provide. Some concepts are difficult to explain. Sometimes, as the adults in young people’s lives, our role is to facilitate conversations that challenge us as well as them. It is our responsibility to imbue students with knowledge, but we never want to teach them what to think.

It is important that we don’t take for granted the ability to filter truth and objectivity from an endless stream of content. Our students are bombarded with a range of opinions, but they are not immune to confirmation bias. Often, however consciously, they will seek out information that validates what they have been told by their parents or peers. Social media is not the enemy. But it rapidly spreads information, useful or not, that many young people instantly absorb as fact. It has always been the role of teachers to offer alternative perspectives – or at least to teach children that they exist. Media literacy is more important than ever, and should be a priority for schools.

My advice for teachers feeling any combination of anxiety, concern or sadness in the aftermath of the events of the summer is to be open and receptive. If your experience of teaching is anything like mine, you will be learning and taking cues from your students. Remember that they don’t need you to have all the answers. They need you to listen to their concerns and show solidarity with their fears. Some students will voice strong opinions that may not be the same ones they will hold as adults. Only have the conversations you are comfortable having, but explain the impact of their words and give them the opportunity to learn.

As a priority, make yourself aware of the support available for staff members and students who have been subjected to racism. Issues of discrimination and violence must be discussed plainly but so too must compassionate responses and resistance. Above all, students need to be reminded that school is a place where they will be protected and are welcome.”

—————————

Introduction written by Liberty Melly, Head of Learning at the Migration Museum and Mona Jamil, Museum Manager at the Migration Museum.

If you are interested in finding out more about the Migration Museum’s learning programme; teacher training, resources, outreach or school and university visits, please contact info@migrationmuseum.org

You can also explore our online learning resources in our resource bank, and sign up to our Learning Mailing List to stay up to date with our latest learning news and resources.

Further reading and useful links:

City of Sanctuary, who coordinate the Schools of Sanctuary scheme, have created a Guide to having courageous conversations about refugee rights.

Facing History and Ourselves ‘Teaching in the Wake of Violence (UK)’ lesson plan

The Economist’s free teaching resource on Media Literacy

We also wanted to share opinion pieces published in the Guardian by two of our Trustees – historian, author, and broadcaster Professor David Olusoga, and author Robert Winder – assessing some of the personal and collective impacts, causes and historical precedents.

There can be no excuses. The UK riots were violent racism fomented by populism – David Olusoga

Look back and see a British history of riots and racial progress. It isn’t pretty, but it is us – Robert Winder

Sources:

1: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/information/refugee-asylum-facts/the-truth-about-asylum/

2: https://www.refugee-action.org.uk/heartbreak-hotels/, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/nov/06/staying-here-is-intolerable-the-truth-about-asylum-seeker-hotels

3: https://www.tenentrepreneurs.org/job-creators-2024

Leave a Reply