The Irish women who built Britain

To mark the Republic of Ireland’s public holiday in honour of their patroness, St Bridgid, Frances Ewings, Gallery Supervisor at the Migration Museum, shines a light on female Irish migration to Britain – in particular nurses who helped build the NHS.

Ethel Corduff and colleagues. Ethel moved from County Kerry, Ireland to Stoke on Trent, England, to work as a nurse in the NHS in 1964. Image courtesy Ethel Corduff

Today marks the Republic of Ireland’s public holiday in honour of their patroness, St Brigid. The day is also a chance to celebrate Irish women, and the impact they’ve had on the world around them.

So what better time to shine a light on female Irish migration to Britain, and in particular, the legions of Irish nurses who helped build the NHS – as featured in the Migration Museum’s exhibition Heart of the Nation: Migration and the Making of the NHS.

And I have a particular interest in the Irish women who emigrated to Britain, as my mum was one of them. And while she didn’t enter nursing, she contributed much by cooking, cleaning and caring for her host nation throughout her working life, spending the last 20 years of her career with Social Services.

Think post-war Irish migration to Britain, and images of men reconstructing a bombed-out Britain may come to mind. And while the contribution of these men to Britain’s progress is undeniable (I take particular pride in the fact that my dad was one of them), what is often overlooked is the fact that from 1951 to 1991 greater numbers of women emigrated to Britain from the Republic of Ireland than men.* These women were often young and travelling alone – atypical in migration patterns.

Ireland was no stranger to emigration, but the situation reached epidemic levels following the formation of the Republic of Ireland in 1949. Having severed ties with Britain, the country struggled politically and economically. This left young Irish people with few opportunities and little choice but to emigrate. The stats are startling – 1.6 million Irish left for Britain in the 20th century – with one in three people under the age of 30 in 1946 having left by 1971.**

The situation was particularly tough for young Irish women. Those from rural areas often missed out on inheriting the farms they lived and worked on in favour of male relatives. Also, the Catholic Church exerted a strong influence over the Irish government, seeing socially-conservative laws and attitudes prevail. For those women who had managed to get an education and themselves into a profession (secondary-school education only became free in 1967), the ‘marriage bar’ loomed over them. This law required single women working in the public, and some parts of the private sector, to leave their posts after marrying, and also prevented married women from applying for such roles. This law was in place until 1973.

Many Irish women decided to take charge of their lives and seek opportunities elsewhere in Britain. One option was a career in nursing. Created in 1948, the National Health Service (NHS) embarked on the herculean task of staffing the new healthcare system. To do so, it looked to Britain’s former colonies, including the Caribbean, south Asia and nextdoor-neighbour the Republic of Ireland.

Irish women were one of the largest groups directly engaged by the NHS. This recruitment drive saw adverts placed in Irish newspapers and NHS staff travelling to the Republic to hold job fairs in order to sign up young women as trainee nurses. The NHS offered an attractive package for these women – training that resulted in a qualification in a respected job-for-life, plus staff accommodation.

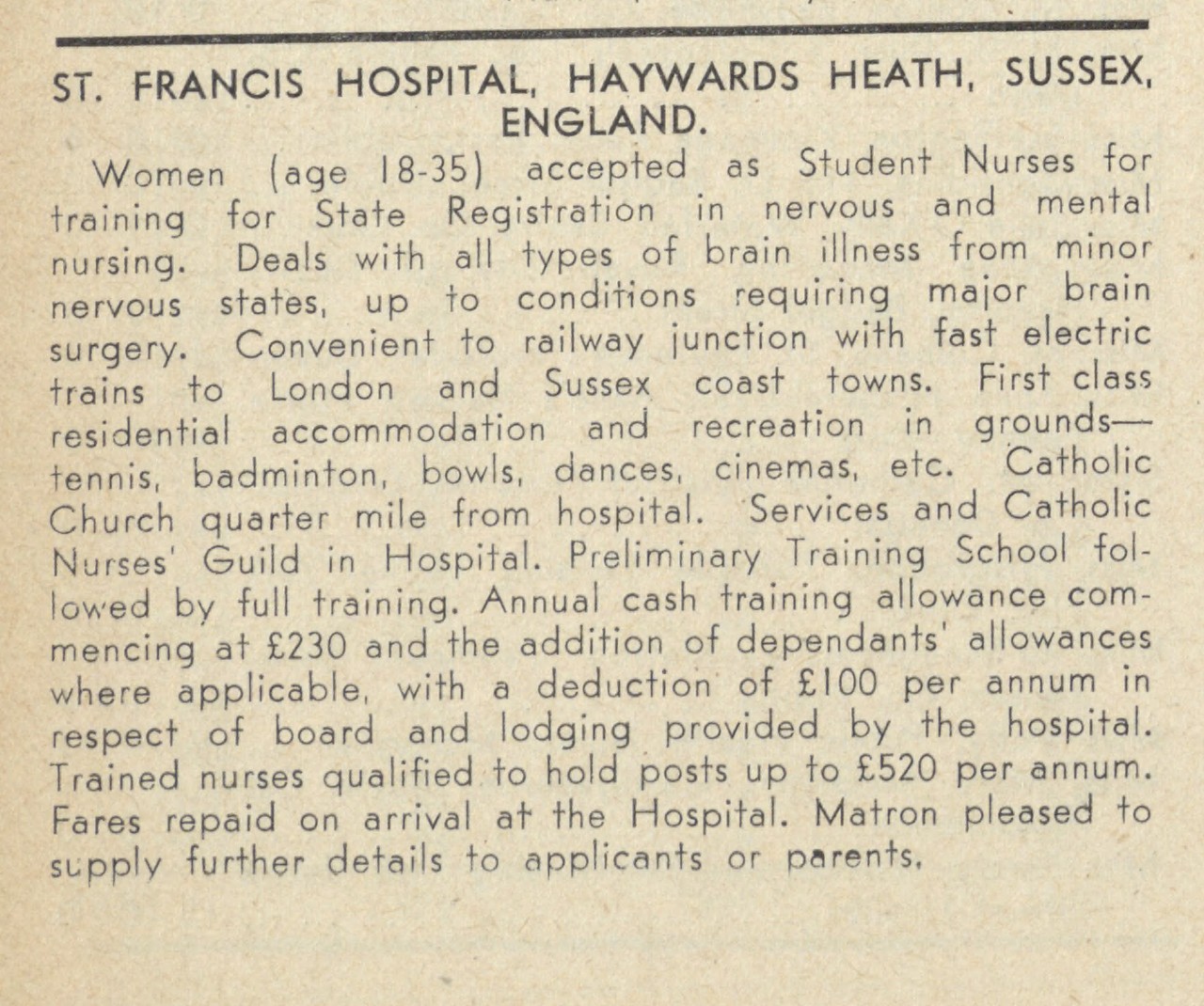

From the Irish Nurses’ Magazine, vol. 21, no. 20 (November 1954). © University College Dublin, National University of Ireland, Dublin. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 DEED (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

In 1964, Ethel Corduff was one of the many women to take up this offer. From County Kerry, Ethel left school at 15 and after a few years of working in low-paid jobs, she answered an NHS advert she saw calling for trainee nurses. In just a few weeks, Ethel – having never travelled outside of Ireland before – found herself in Stoke-on-Trent, England to begin her training.

Ethel Corduff as a nursing student at the City General Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent, in 1966. Image courtesy Ethel Corduff

And despite a rocky start, (she tried to quit three-weeks in, due to a fearsome matron and crippling homesickness) she went on to forge a successful career as a nurse, rising to acting ward manager by the time of her retirement. Many Irish women made similar journeys, and by 1971 there were 31,000 Irish-born nurses in Britain, making up 12 percent of all nursing staff.***

While the numbers are smaller today, those women paved the way for others and ensured a tradition of Irish care within the NHS that still exists today.

St Brigid would be proud of them all.

Ethel’s is just one of the stories we feature on Irish nurses in our touring exhibition Heart of the Nation: Migration and the Making of the NHS, currently on in Leeds until 18 February, and opening at the Migration Museum in London from 7 March 2024. The exhibition can also be explored online.

Ethel Corduff is the author of Ireland’s Loss Britain’s Gain: Irish Nurses in Britain Nightingale to Millennium. She also features in Angels of Mercy, a 2021 documentary on Newstalk which also references our Heart of the Nation exhibition.

SOURCES:

Really interesting read.

Thank you for this. Excellent article. My mother was in fact one of those girls who went to England to do her nursing just after the war. My sister and I were just talking about it because my mother never really spoke of when she went or why. so this feels in a lot of background for us.