How can we convey the complex issues of migration and welfare to school students?

In the second of three blogs on holding workshops with school pupils on the issues of migration, Umut Erel and Elizabeth Newcombe discuss an attempt to introduce pupils to the complexities of the language and the policy issues surrounding immigration, at a time of great global inequality and economic recession.

When holding a workshop for a school from Sussex at the Migration Museum Project’s Call Me By My Name exhibition in July 2017, it was striking to see school pupils becoming passionately engaged with issues of migration. The group of 15 pupils and their teachers arrived on one of the hottest days of the year, having already spent time wandering through London. Emily Miller, MMP’s head of learning and partnerships, started the workshop with an interactive game, using questions and movement in the space of the museum to break the ice and find out how everyone relates to migration. Some of the questions she asked were:

- Do you know someone who has migrated?

- Do you speak more than one language?

- Has anyone in your family migrated?

If our answer to these questions was ‘yes’, we had to take a step forward; if the answer was ‘no’, we were asked to take a step backwards. Soon most of us were concentrated in a tight circle in the middle of the room, and it had become clear that there was a lot of experience of migration, whether personal or indirect.

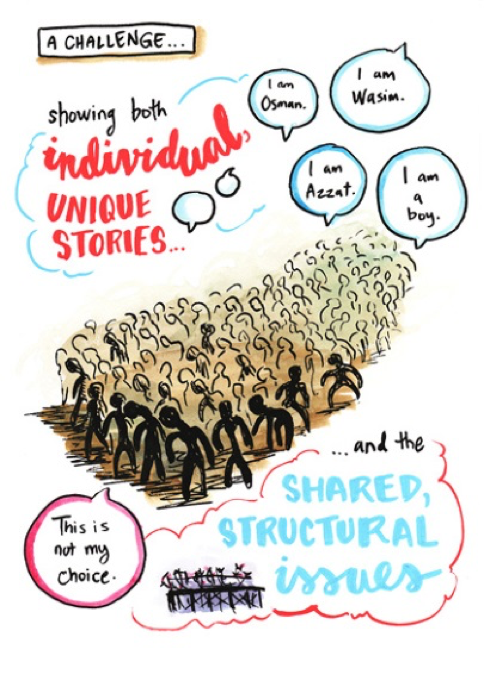

Drawing by Laura Sorvala.

The workshop then moved on to look at some of the key terms in the migration debate. A young refugee told of his experiences of migration, finding his way around life in the UK and how he now works in arts and education organisations in which he initiates dialogues on the experiences of refugees and migrants. All of us were stunned to hear of the difficulties he had overcome on his journey to the UK in the early 2000s. Some of the pupils shared their personal experiences of the country he came from and the countries he had passed through, which gave the encounter added poignancy.

After this informative and emotionally charged part of the workshop, we changed gears slightly and introduced a more academic take on the issues. Starting with an interactive exercise on global inequalities of income, we began to question the term migrant, pointing out that, when we use the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’, this does not refer to a legal figure or a dataset, but to a political figure. We discussed how British people living abroad almost always think of themselves as ‘expats’ not ‘migrants’, while Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people who were born and have lived all their lives in the UK are often called ‘second generation migrants’. So, the decision about who counts as a migrant is often framed by assumptions about race, class and nationality.

When discussing migration, we often hear about the need to protect the welfare state from outsiders, but how can we understand the welfare state against the backdrop of global inequalities? We are living at a time of the highest level of global inequality in human history, when the wealth of 67 people is the same as the combined total of the world’s 3.5 billion poorest people, and the poorest 50 per cent of the world have 6.6 per cent of total global income. There are issues with the methodology of these estimates, but it cannot be denied that the world has changed from the 19th century. Today, for most people in the world, what is key to your life chances is the country you live in. The fear for those living in wealthier states is that there are a lot of people who are hard up in the world and that, if you don’t have much, you need to hold on to it.

Photo of the PASAR project’s ‘From Margins to Centre Stage’ workshop, February 2017 © Marcia Chandra.

Migrant families’ exclusion from the welfare state was a topic in another research project – Participation Arts and Social Action in Research (PASAR) – we are currently running with our colleagues Erene Kaptani (Open University), Maggie O’Neill (University of York) and Tracey Reynolds (University of Greenwich). The PASAR project conducted participatory research with migrant mothers affected by the policy No Recourse to Public Funding (NRPF), which means migrants who are subject to immigration control are not allowed to access benefits, tax credits or housing assistance. This policy affects both migrants who have the right to remain in the UK and those who are undocumented. The policy pushes these migrant families – many of whom include young children, who are among the most vulnerable people – to the margins of society through poverty and racism. In a workshop with policy makers, practitioners and activists, we worked with a group of migrant mothers affected by NRPF to enable their collective voice to be heard. To do so, we showed a short theatre piece developed through the research.

Photo from PASAR project theatre scene © Marcia Chandra.

At the schools’ workshop, we watched a short scene from this theatre piece about Elaine’s experience. Elaine had been working for many years for a large supermarket. She needed to take time off every two weeks to sign into the Immigration Reporting Centre, a requirement of the Home Office. Her manager used his knowledge of her vulnerability to bully her and change her onto an unfavourable night shift, even though she had just had a baby. Her union representative’s response was that as an immigrant she should be glad to have a job. She also experienced stigmatisation by fellow workers, who saw her as an ‘illegal’ immigrant. Eventually, she lost her job – unable to pay rent, Elaine, her husband and six-year-old son have for four years now been living in the houses of friends and acquaintances, surviving on their monetary support.

This example shows how racism, anti-immigration policies and austerity intersect. An increasingly hostile climate to immigration has made it more difficult for migrants to find formal and informal employment. As a consequence of increasingly stringent migration regulations, particularly since 2012, more and more migrant families are subject to migration control, prevented from accessing public funds and rendered unable to economically support themselves (Price and Spencer, 2015). In a situation of crisis – through the loss of jobs or accommodation, relationship breakdown or health problems – they cannot draw on the relative safety net of the welfare state to help them overcome these points of crisis and are pushed more and more to the margins of society.

Having watched a short video clip of these theatre scenes with the school pupils, we had an interesting discussion about some of the issues raised by Elaine’s story:

- How can labels such as ‘illegal migrant’ be misleading and stigmatising?

- Why are some people, and not others, allowed to draw on welfare services?

- Should contributions through work be the criterion for deciding whether migrants can participate in the welfare state?

- Should there be other criteria for inclusion into welfare, based on colonial and postcolonial ties?

- Should there be criteria based on shared humanity?

It is hard to summarise the workshop, as it was rich and varied, but it seems to me that this variety of modes of engagement (personal testimony, interactive activities, and audio-visual material and information) has been fruitful in raising many questions, showing the complexity of issues of migration and welfare, and linking conceptual discussions to personal experiences of migration, which are often far richer than those portrayed in public debate. While teachers challenged us as academics to present information in accessible ways, especially for pupils who are still learning English, their feedback was heartening: ‘Our students learnt a lot from the experience both about migration at the human level but also the bigger picture of why these issues are so pressing for the UK at the present time. A great day well spent!’

Reference

Price, Jonathan, and Spencer, Sarah (2015) Safeguarding Children from Destitution: Local Authority Responses to Families with ‘No Recourse to Public Funding’. Oxford: COMPAS.

Umut Erel is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the Open University. She is Principal Investigator of PASAR, an ESRC-funded research project investigating the opportunities and challenges of using participatory theatre and walking methods for social research.

Emma Newcombe is the Head of External Relations for COMPAS and the Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity. She oversees all COMPAS’s communications work, and also supports the development of the ESRC Urban Transformations project. She has an MA in Migration Studies from the University of Sussex and a BSc in Social Policy from the University of Bristol.

Leave a Reply