29 January, 2019

Historian and Migration Museum Trustee David Olusoga visits Manchester, which along with the other industrial manufacturing towns surrounding it, acted as a magnet for waves of economic migrants from all over the world. In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, 30,000 Jewish migrants from Russia and Eastern Europe settled in Manchester.

Olusoga meets Janice Haber and her family, the descendants of Jewish migrants, and talks to historian Ruth Percy who describes how Conservative politicians and right wing newspapers of the time exploited economic concerns associated with the new migrants, stoking up racist xenophobia against migrants like the Jews, which would become familiar throughout the 1900’s. The arrival of the Jews and other migrants led to changes in the law, and to the emergence of modern immigration legislation – laws that persist to this day.

Click here to watch (external link to BBC website)

26 April, 2019

This is a short posting about football, but really it’s mostly about forgiveness.

At a time when divisions run deep and animosity is in the air, when Crystal Palace’s goalkeeper is apparently ‘desperate’ to learn about the Second World War if only to understand why the Nazi salute he was photographed making might have been inappropriate, and when Manchester City seemed poised to perform a unique domestic treble*, it seems appropriate to tell the story about Bert Trautmann.

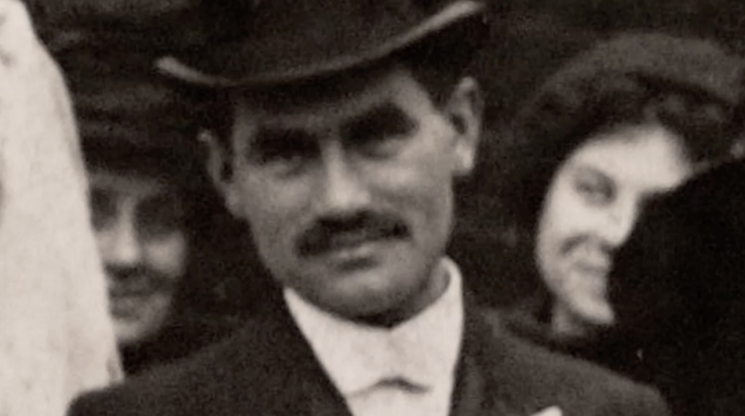

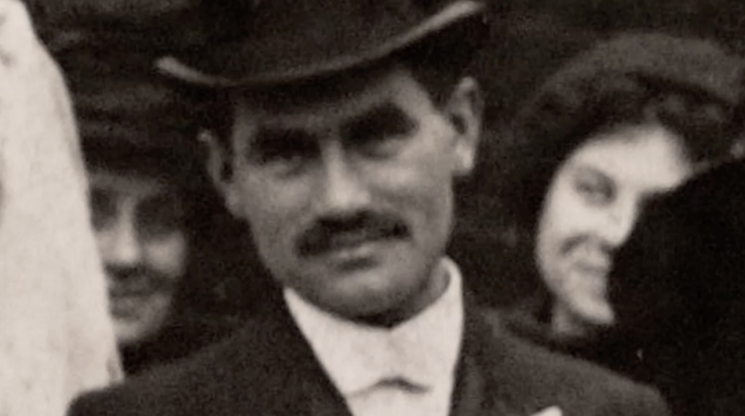

The Manchester City goalkeeper Bert Trautmann (1923–2013) in action.

Bernhardt Trautmann was selected as Manchester City’s goalkeeper when the popular, well-respected goalkeeper Frank Swift retired at the end of the 1948/49 season. Difficult enough to fill the shoes of the England team’s goalkeeper (and someone who, ironically for an ex-Manchester City player, died in the 1958 Munich air disaster) and a player considered at the time to be the best keeper Manchester City had had; harder still when you had spent most of the last four years in a prisoner-of-war camp in Lancashire as a captured German who had fought on both the Eastern and the Western fronts with distinction, winning five medals in the process; even harder when the team you are about to play for is in a city with a significant Jewish population, which, to put it mildly, didn’t take kindly to the idea of a Nazi playing for one of its clubs.

In October 1949, 25,000 fans protested outside Maine Road (the club’s football ground) against Trautmann’s selection – accusing him of being a Nazi (which he certainly had been) and a war criminal (for which there was then – and maybe still now – no proof) and threatening to boycott the club if it didn’t cancel his selection.

We couldn’t find a photo of the 1949 protest by Manchester City fans, but this is a Manchester protest on climate change, which is relevant in a week of Extinction Rebellion activity even if not appropriate to this blog . . .

This was, after all, five years after the end of the Second World War, when the full scale of the Nazis’ massacre of the Jews was still emerging. As the poet TS Eliot wrote, ‘After such knowledge, what forgiveness?’

Enter at this point two extraordinary heroes. The first was the Manchester City team captain, Eric Westwood, who had taken part in the D-Day landings and who, on being introduced to Trautmann, was reported to have said ‘There’s no war in the dressing room. We welcome you as any other member of the staff. Just make yourself at home, and good luck.’

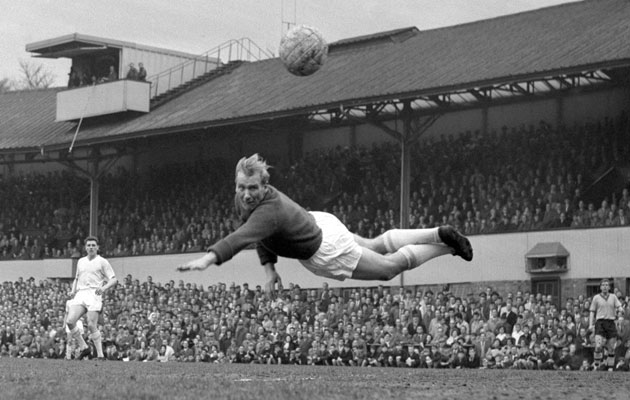

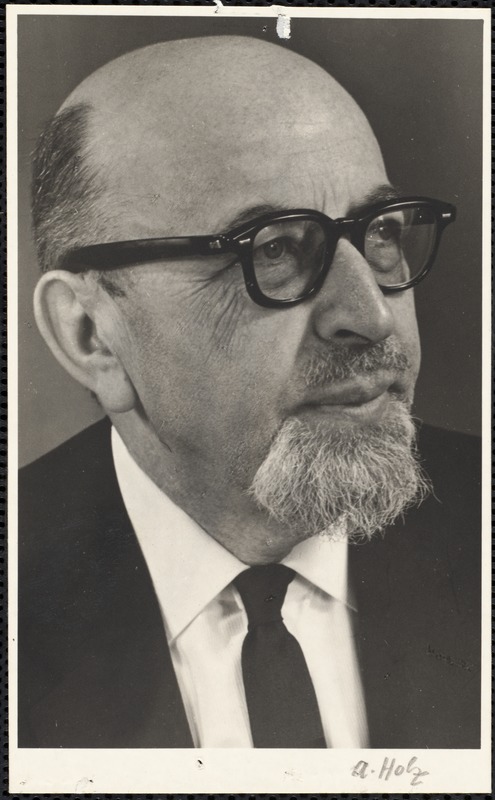

The second was Alexander Altmann, a communal rabbi living in Manchester, whose parents and other family members had been killed by the Nazis. Altmann wrote a letter to the Manchester Evening News in which he said, ‘Each member of the Jewish Community is entitled to his own opinion, but there is no concerted action inside the community in favour of this proposal [to force Trautmann out of the club]. Despite the terrible cruelties we suffered at the hands of the Germans, we would not try to punish an individual German, who is unconnected with these crimes, out of hatred. If this footballer is a decent fellow, I would say there is no harm in it. Each case must be judged on its own merits.’

Alexander Altmann (1906–87), a communal rabbi in Manchester and the founder of the Institute of Jewish Studies, who spoke out in support of Bert Trautmann.

After such knowledge, to repunctuate TS Eliot, what forgiveness!

Largely as the result of these two interventions, the animosity against Trautmann abated, and he went on to have an illustrious career for Manchester City, playing for the club for fifteen years (1949–64), most memorably in their successful 1956 FA cup final against Birmingham City, in which he played the last fifteen minutes with a broken neck, having dislocated five vertebrae on colliding with an opposition player when diving for the ball. (Giving Trautmann his winner’s medal, Prince Philip apparently commented on how crooked his neck seemed.)

The moment in the 1956 FA cup final just before Trautmann, diving for the ball, collided with the foot of Birmingham City’s Peter Murphy (right), sustaining five fractured vertebrae.

There are two more heroes in this story. The first is Trautmann himself, who put himself through the kind of re-education that perhaps Wayne Hennessey (the Crystal Palace goalkeeper mentioned previously) should now consider – spending time engaging with the Jewish communities in Manchester, listening to them, talking to them about the national brainwashing that he felt had been practised in the Germany of his youth, and distancing himself (insofar as it is possible to do so) from the party he admitted to have followed blindly as a young man. And the second is the fans of Manchester City themselves, who took Trautmann to heart despite their early reservations and protestations.

Three Manchester City supporters in Trafalgar Square, psyching themselves up for the 1956 FA cup final.

It is easy to be cynical about this story and to say, rightly, how surprisingly straightforward we find it to overlook people’s migrant status (and, in Trautmann’s case, to forgive their crimes) when it serves our purpose to do so, how posting ‘successful migrant’ stories such as this (or those of Mo Farah, Jessica Ennis-Hill or Ian Wright) draws a decorous veil over the daily reality of racism and xenophobia experienced by migrants, how much easier it is to apologise for committing atrocities than it is to take a stand against them in the first place – to point, also, to the worrying recent resurgence in racist behaviour towards football players of colour. All of that is true, but Bert Trautmann’s story continues at the least to show that people are capable of change, even when memories of collective suffering are so fresh in their minds. It’s a small story of hope.

And, for the record, this blog is being posted by a supporter of Manchester United, two days after Manchester City humiliated them at Old Trafford with a 2–0 victory that will probably hand City the Premier League title. What greater forgiveness can there be than that?

*The domestic treble, in football terms, involves the Premier League title, the FA cup and the Carabao Cup (also known as the English Football League Cup). Manchester City have already won the Carabao Cup.

For those interested in finding out more about Bert Trautmann’s story, the recent film The Keeper is a good place to start. For those wanting to read about his life, a good place to start is Catrine Clay’s 2011 biography, Trautmann’s Journey: From Hitler Youth to FA Cup Legend.

We’ve not been able to track down a biography of Alexander Altmann but would love to hear about one.

Kick It Out is the organisation devoted to fighting against discrimination in football.

And we can’t resist the opportunity to plug our 2014 exhibition, Germans in Britain, which is currently in wraps but which you can read the brochure about here.

29 January, 2019

During the 1800s tens of thousands of poor Irish labourers and their families left Ireland to find work in Britain during the Industrial Revolution. Large numbers came to, and settled in, Liverpool, and faced terrible conditions. Cholera and other diseases spread and their arrival eventually promoted the beginning of the British public health system.

Historian and Migration Museum Trustee David Olusoga visits Liverpool Public Record Office and meets local historian Sam Caslin who is an expert on this period in Liverpool’s history. They look at the contribution of Irish migrants to Britain’s Industrial Revolution, and how this country owes much of our transport network and housing stock to their work here.

Click here to watch (external link to BBC website)

29 January, 2019

European powers started trading with India from the early 1500s. At first, all British trade was dominated by the London based East India Company, which was granted the monopoly on trade with India in 1600. Over the following 200 years the company became increasingly prominent in the European trading routes with India.

Historian and Migration Museum Trustee David Olusoga meets Professor Margot Finn, an expert on the period, and profiles the Russell family who purchased Swallowfield House near Reading, which is today a block of luxury flats. The house symbolises how these so called Nabobs, British migrants in the employ of the East India Company, returned from India extremely wealthy men, which allowed them to establish themselves at the higher end of the British class system.

Click here to watch (external link to BBC website)