25 October, 2019

A unique archive of photographs which records the changing face of a British industrial city through the 20th century is now being brought to a national audience in a BBC documentary, as Tim Smith, long-term friend and supporter of the Migration Museum, recounts.

When the Belle Vue Studio opened in 1926 on Manningham Lane in Bradford, the owner, Benjamin Sanford Taylor, installed his old Victorian glass-plate camera on a tripod at one end of his photographic studio. At the other end of the room was the spot for Belle Vue’s customers who, lit by daylight falling through a glass wall and roof, faced a lens which never moved until the business closed in 1975.

The studio remained unchanged for 50 years, but the city outside was transformed. People had always come from other parts of the UK and Ireland to work in Bradford, the centre of the world’s woollen textiles industry, but from the 1940s onwards increasingly large numbers came from further afield.

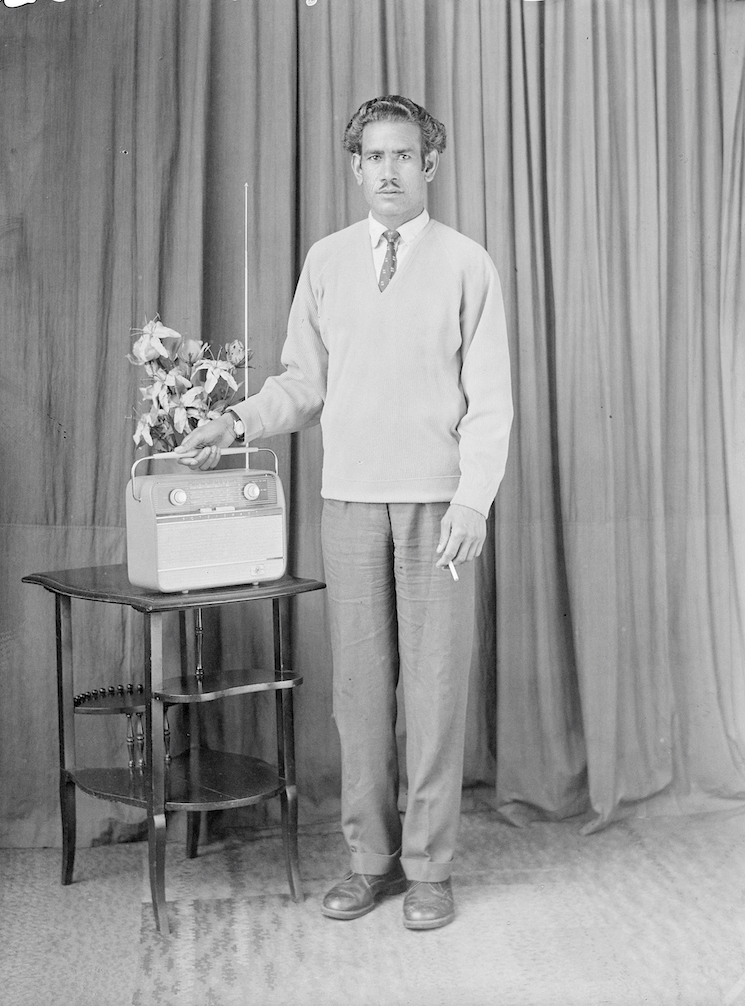

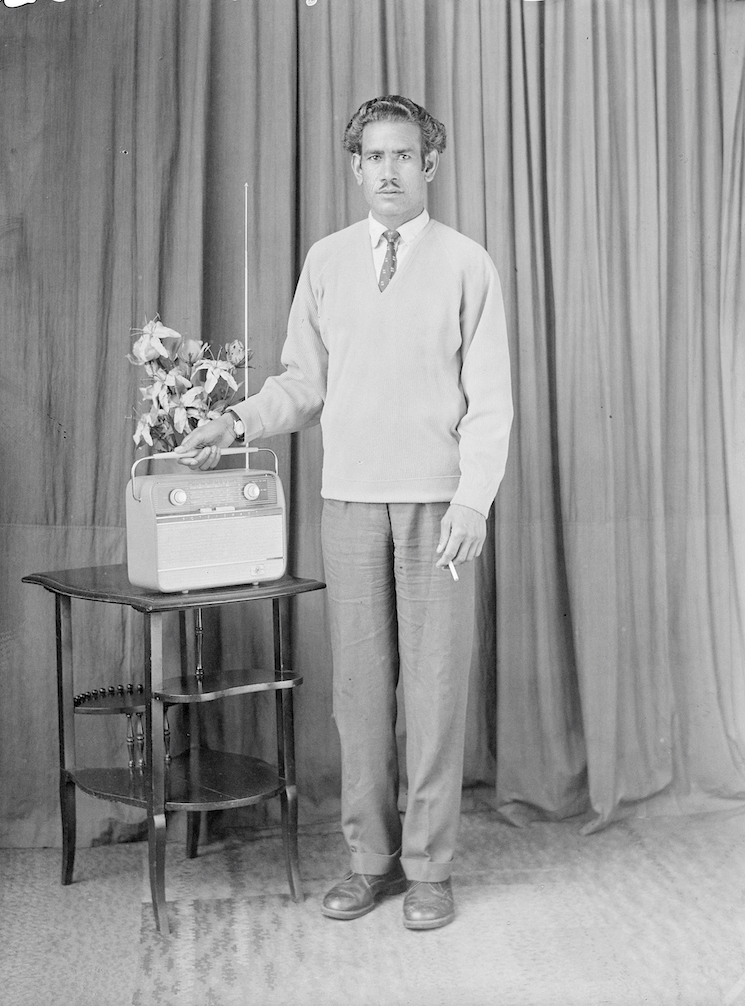

Man with radio at Belle Vue Studio, Bradford (further details unknown) © Bradford Museums and Galleries

Many of these migrants settled in inner-city Manningham, where cheap housing and jobs were plentiful. The Belle Vue Studio was ideally located for them and it produced the old-fashioned style of picture that they were familiar with from their homelands. It became the studio to visit for these new arrivals.

This is reflected in the identities of the subjects of the photographs. Before the Second World War (1939–45) the faces in the pictures almost all belonged to white British and Irish people. This changed dramatically after the war, with the photographs revealing a much greater diversity among the customers.

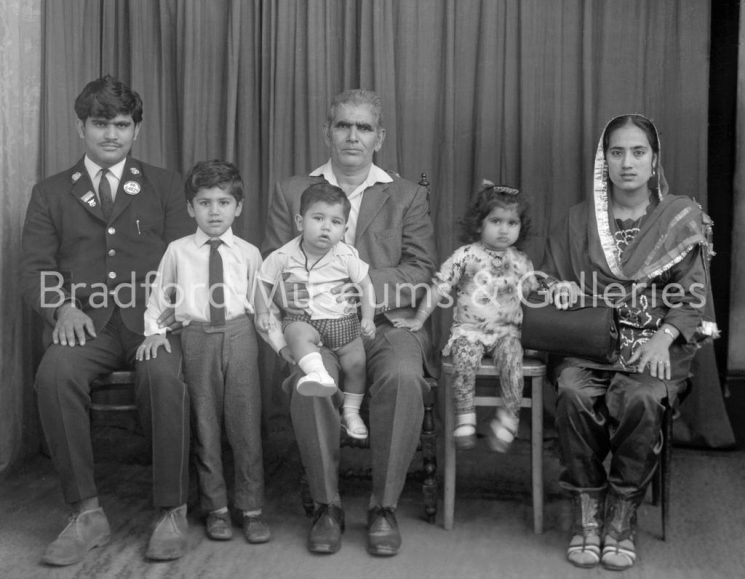

The first new arrivals, in the late 1940s, were post-war political refugees from Poland, Ukraine and other parts of Eastern Europe. During the 1950s families from the Caribbean and groups of single men from the Asian sub-continent appear in the frame. In the 1960s these men were joined by their families, and new generations of children born in Bradford can be seen in the photographs.

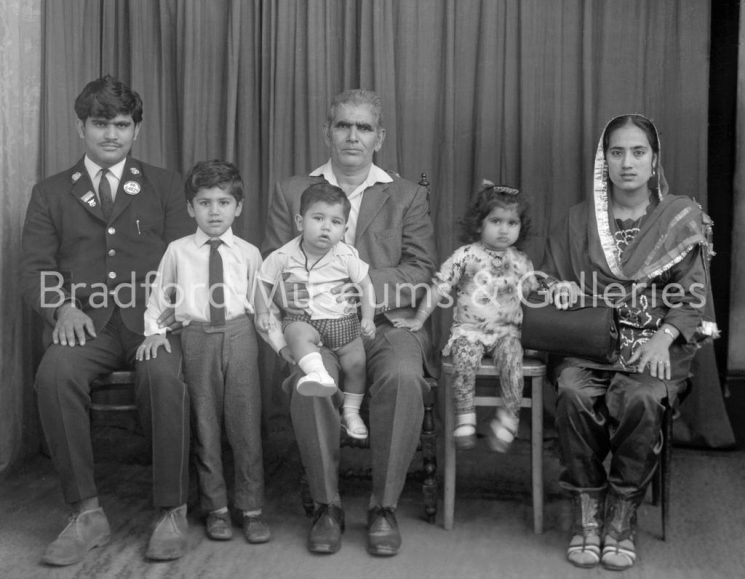

A family grouping at the Belle Vue Studio, Bradford (further details unknown) – note the bus uniform worn by the man on the left © Bradford Museums & Colleges

All these migrant communities came seeking a better life in Bradford, working mainly in the textile industry, in the newly created NHS, in the expanded public transport networks, or as factory workers in other industries.

I first encountered these extraordinary photographs shortly after the Belle Vue Studio was sold in 1986. The photographer Tony Walker, who had bought the business when Sanford Taylor retired in the 1950s, closed the studio when his wife fell ill. For a decade thousands of glass-plate negatives lay forgotten in a dark, damp cellar. When Tony Walker found a buyer for the building, he began filling a skip outside with what he thought was the studio’s redundant archive.

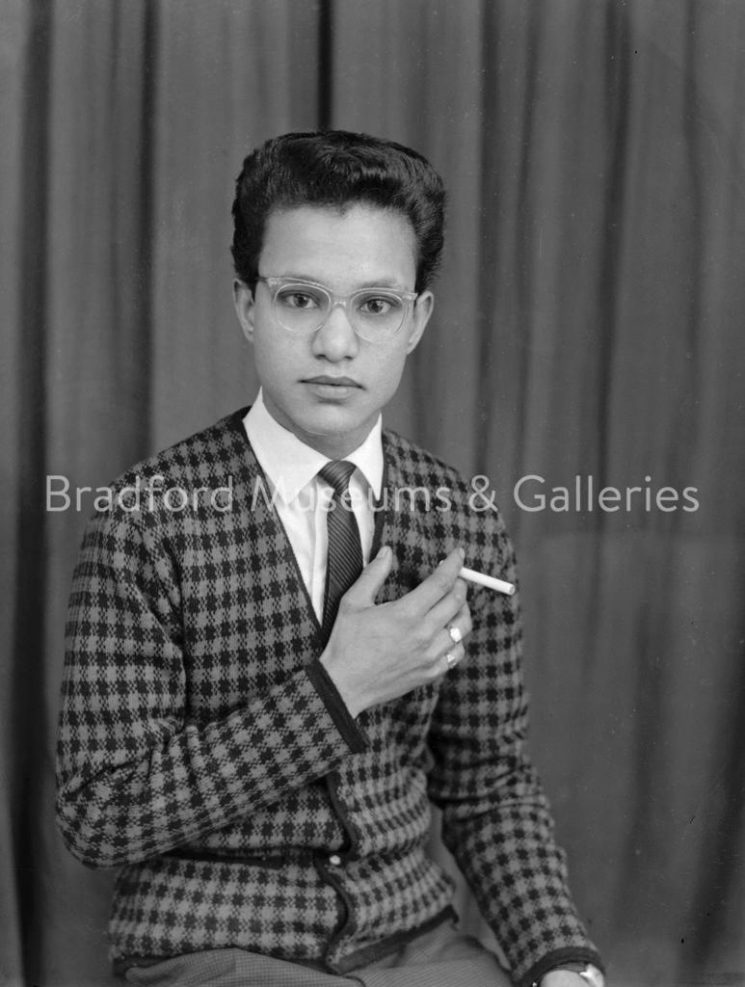

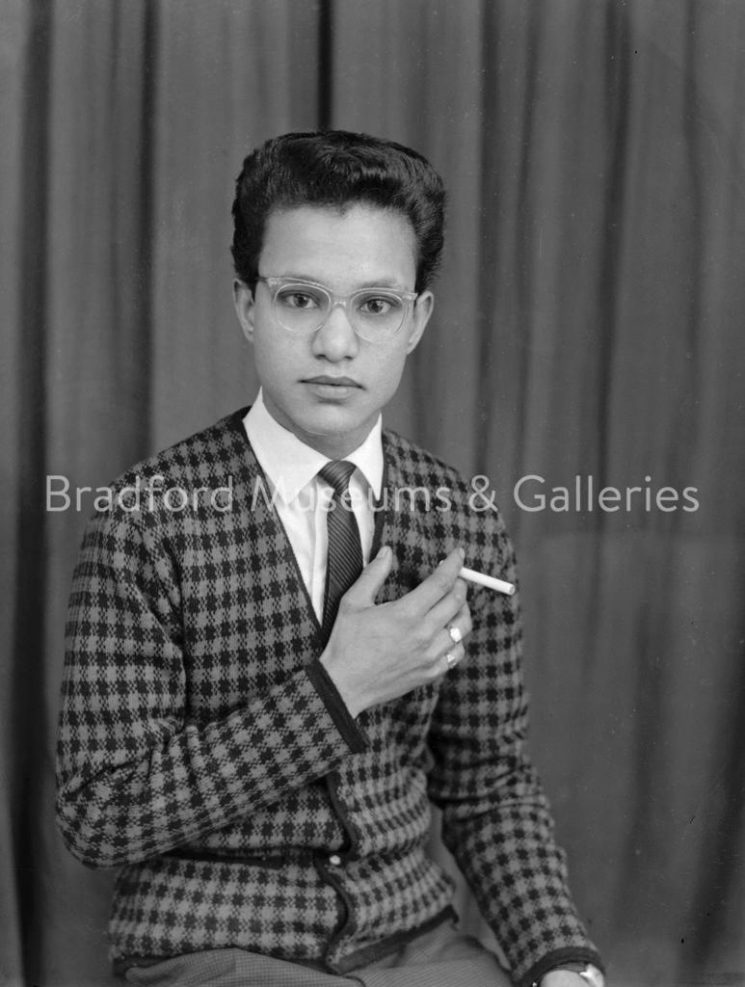

A young man at the Belle Vue Studio, Bradford (further details unknown) © Bradford Museums & Galleries

Luckily, the new owner saw some of the pictures, realised their significance and forbade Tony to throw away any more. He brought a small number to the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit, for which I was working at the time, leading a team that was creating a photographic archive on behalf of Bradford Museums.

Many of the pictures had been destroyed, but we acquired those that survived, more than 17,000 glass-plate negatives stored in damp and dirty show boxes. After much painstaking work by staff at Bradford Museums they are now housed in stable, archival conditions, forming a rare and invaluable record of Bradford at a time of extraordinary change.

Two young women pose in girl-guide uniform at the Belle Vue Studio, Bradford (further details unknown) © Bradford Museums & Galleries

As a result of a collaboration between Bradford Museums and Bradford’s National Science and Media Museum the majority of these negatives have now been digitised.

As part of the Bradford’s National Museum Project, which is run by the University of Leeds and aims to foster better connections between the National Museum and local partners and communities, we have been running a series of pop-up exhibitions around the city and using the photos as a catalyst for seeking out the stories of those who visited the Belle Vue Studio more than forty years ago. Many of these stories, together with some remarkable images, are shared in the television programme Hidden Histories: The Lost Portraits of Bradford, which will be transmitted on BBC4 at 9pm on 28 October, and which will be available on iPlayer for 30 days thereafter.

The film Hidden Histories: The Lost Portraits of Bradford will be screened on BBC4 at 9pm on 28 October 2019, and available thereafter on iPlayer for 30 days.

More than 10,000 photographs from the Belle Vue Studio are available to view on the Bradford Museums & Galleries website.

14 October, 2019

We were told that the absence of a large screen was due to the Extinction Rebellion protests in Westminster Square. The reason for the absence of anything but a small handful of MPs was not given, so we could only speculate: XR as well? Brexit-induced agoraphobia? indifference to the plight of Syria and its citizens? or shame at the UK’s limited response to the crisis?

Without a large screen to focus on, we watched the film on a bank of much smaller screens, which would normally be relaying procedures in the Houses of Parliament across the road. We were gathered in Portcullis House (the Westminster building that provides office space for MPs) for a special screening of For Sama, an extraordinary film by Waad al-Kateab and Edward Watts that has been picking up prizes and plaudits around the world since its release earlier this year, and which has now been released in the UK.

For Sama is the film debut of Waad al-Kateab and is a record of four years in Aleppo, from the Syrian uprising to the conclusion of its brutal suppression in 2016, when Russian bombers combined with Syrian army forces to obliterate the last traces of resistance, bombing hospitals in violation of all international law, human decency and common fellow-feeling. Waad, the director as well as the key player of the film, charts her part in the events from enthusiastic supporter of the revolution, to her marriage to Hamza (the main doctor in the hospital where much of the film is shot), to the birth of their daughter Sama and their eventual escape from Aleppo, with government forces closing in on the hospital from a street away.

Waad, Hamza and Sama look at graffiti they painted on a bombed-out building, protesting against the forced exile of the civilian population of east Aleppo by forces of the Syrian regime and their Russian and Iranian allies, December 2016. © PBS Distribution: For Sama

You can see why so many MPs may have chosen to stay away from this screening. For Sama is a very difficult film to watch. On one level, it’s a fairly conventional love story, showing Waad and Hamza (married at the start of the film, he stays in Aleppo to look after the hospital while his then-wife seeks safety elsewhere) becoming friends, falling in love and tending to their new-born daughter, a child who hardly ever cries. The film is shot on Waad’s own hand-held camera and smartphone and has a freshness, a lack of artifice and an authenticity that would make it compelling even if this were the full story.

But, of course, it’s not. The love story is set against the relentless bombardment of Aleppo by Syria’s President Assad’s forces, gleefully supported by Putin’s air force and artillery. The hospital, the main stage on which this tragedy is played out, receives a daily ration of hundreds of victims, whom Hamza and his fellow medics and supporters do all they can to patch up and repair. Miracles are few and far between – though in one a baby, born dead, it appears, from his apparently dead mother, is eventually coaxed and slapped back into life, and the mother too lives. For how long, we are not told. More often, though, the blue sheet is pulled up over the face of the patient, who will then be buried in whatever halfway-dignified circumstances a city so completely under siege allows.

Waad’s camera is unflinching, capturing the distress of a mother who insists on carrying her dead child out of the hospital herself, the dusty numbness on the faces of the two brothers when they are told what they must already have guessed: that the brother they have just brought into the hospital, the last surviving member of their family of ten, is himself dead.

There are moments of relief: the extraordinarily loving family who shares living quarters with Waad’s family in the hospital, the Waad–Hamza–Sama relationship itself, and the unquestioning readiness of people to sacrifice their lives in the service of other people and the belief in and love of their country.

Hamza (with glasses), Sama and the staff of al-Quds hospital, which Hamza set up in 2012 in east Aleppo. © PBS Distribution: For Sama

The focus is on one woman’s camera, documenting her experiences in one hospital in one city in a country ripped apart by conflict. But watching it in Portcullis House you feel, as the main actors in the film must have felt, the painful absence of any countervailing presence, any response – at international or national level – to the despicable violence brought down on these players by a government bent on its own preservation.

So . . . easy to see why so many MPs may have chosen to keep away from the film. But we would urge you to see the film if you can. It is on general release now (details available from the film’s website) and the Migration Museum hopes to be screening it over the coming months.

Above all, it is impossible to watch this film without hearing in your mind the comments made in newspapers, on the radio and elsewhere in this country about immigrants coming to this country purely for their own economic advantage. This film scotches the lie about economic migrants. Until the last moment, when Waad’s camera shows the utter devastation of the once so beautiful Aleppo, none of the people who appear in the film had any thought about leaving the city and the country they love. Anyone who believes that most migration is undertaken for selfish economic advancement should see this film.

Sama pictured in September 2016, in the bombarded east of the city, with a placard in response to US presidential candidate Gary Johnson’s infamous gaffe: “What’s Aleppo?” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fOT_BoGpCn4) © PBS Distribution: For Sama

With the increasing popularity of online genealogy tools and DNA testing kits, and the long-running success of programmes such as Who do you think you are?, there is a growing desire to find out where we come from and to uncover the stories of the ancestors that brought us here. But many of us don’t know where to start – or have become stuck in our research and don’t know where to turn next.

The Migration Museum’s Family History Day, taking place in central London on Saturday 2 November 2019, offers an accessible way for audiences of all ages and backgrounds to unlock and explore their family’s story.