Adweek – Ad Campaign for Euro 2020 Shows Migration’s Pivotal Role in ‘the Beautiful Game’ (16/06/2021)

The Migration Museum in London highlights the diverse immigrant backgrounds of soccer players

The Migration Museum in London highlights the diverse immigrant backgrounds of soccer players

The Migration Museum is launching a new campaign running throughout the Euros this summer highlighting how migration has shaped the beautiful game.

A personal essay by our trustee George Alagiah on why Britain needs a permanent Migration Museum.

The passengers of the Mayflower were men, women and children. 102 of them left Plymouth on 6th September 1620. Who were they and why were they leaving?

This guest blog post by Jo Loosemore, curator of Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy – the national commemorative exhibition for 2020/21 in The Box, Plymouth, is part of Departures: 400 Years of Emigration from Britain – Partner Stories, a national series to accompany the Migration Museum’s Departures exhibition and podcast.

The passengers of the Mayflower were probably not the people you think they were. For over 400 years, we’ve thought of them in black and white – literally and metaphorically. They’ve worn monochrome, and their motivations have had very few shades of grey. But their actual stories are much more colourful.

Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy at The Box, Plymouth

On 6th September 1620, 102 passengers left Plymouth on board the Mayflower. They were men, women and children. They were people of different ages, classes, backgrounds, and birthplaces. These migrants were far more demographically diverse than most stories about them suggest.

There were 19 family groups on board – mothers and daughters, fathers and sons. There were three pregnant women too, and over 30 children. Some were just babies or toddlers, others were young people, and four siblings – all under the age of 10 – travelled without their parents. The passengers of the Mayflower also included older couples in their 50s and 60s. There were people of different classes – some highly educated, whilst others were indentured servants. The 102 included a mix of professions too, with printers, hat-makers, merchants and shoe-makers on board the ship bound for America.

Later artists have given us their impressions of these early English migrants, and their black hats, belts and buckles have lived long in popular memory. Yet these travellers were far more vivid than that. They wore reds, pinks, orange and yellow. They were young, old, rich and poor. Each passenger had their own individual story. Yet we only have one image of one of them painted during their lifetimes – it’s a portrait of Edward Winslow, the first man to write about the colony they created on the other side of the Atlantic.

Portrait of Edward Winslow, from the collection of the Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, MA, USA

The words of his fellow migrant, William Bradford, have shaped our understanding of who the passengers on board the Mayflower were for centuries. His text, Of Plimoth Plantation, suggests that they were a largely homogenous group, with similar beliefs, motivations for leaving their lives, their homes, and in some cases, their families too. His was the Separatist story – a community of English religious exiles in Holland from 1608, who decided to cross the Atlantic 12 years later. But could 102 people of differing ages, classes and connections all have the same reasons for leaving? The same aspirations, hopes and fears? We don’t have their personal stories, so William Bradford, over time, has come to speak for them all. Yet even he reveals different motivations for departure –

Community

‘It was thought that if there could be found a better and easier place of living, it would attract many…’

Age

‘Old age began to steal on many of them, and their great and continual labours, with other crosses and sorrows, hastened it before their time.’

Children

‘Many of their children…were led by evil example into dangerous courses…so they saw their posterity would be in danger to degenerate and become corrupt.’

Religion

‘Last and not least, they cherished a great hope and inward zeal of laying good foundations, or at least of making some way towards it, for the propagation and advance of the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in the remote parts of the world, even though they should be but stepping stones to others in the performance of so great a work.’

Bradford may have spoken for the Separatists, but does he describe the thoughts and feelings of the other Mayflower passengers too?

Family historians have researched many of those 102 people who left England four hundred years ago. They’ve told us about their births and birthplaces, marriages and children, and, in many cases, the people they left behind.

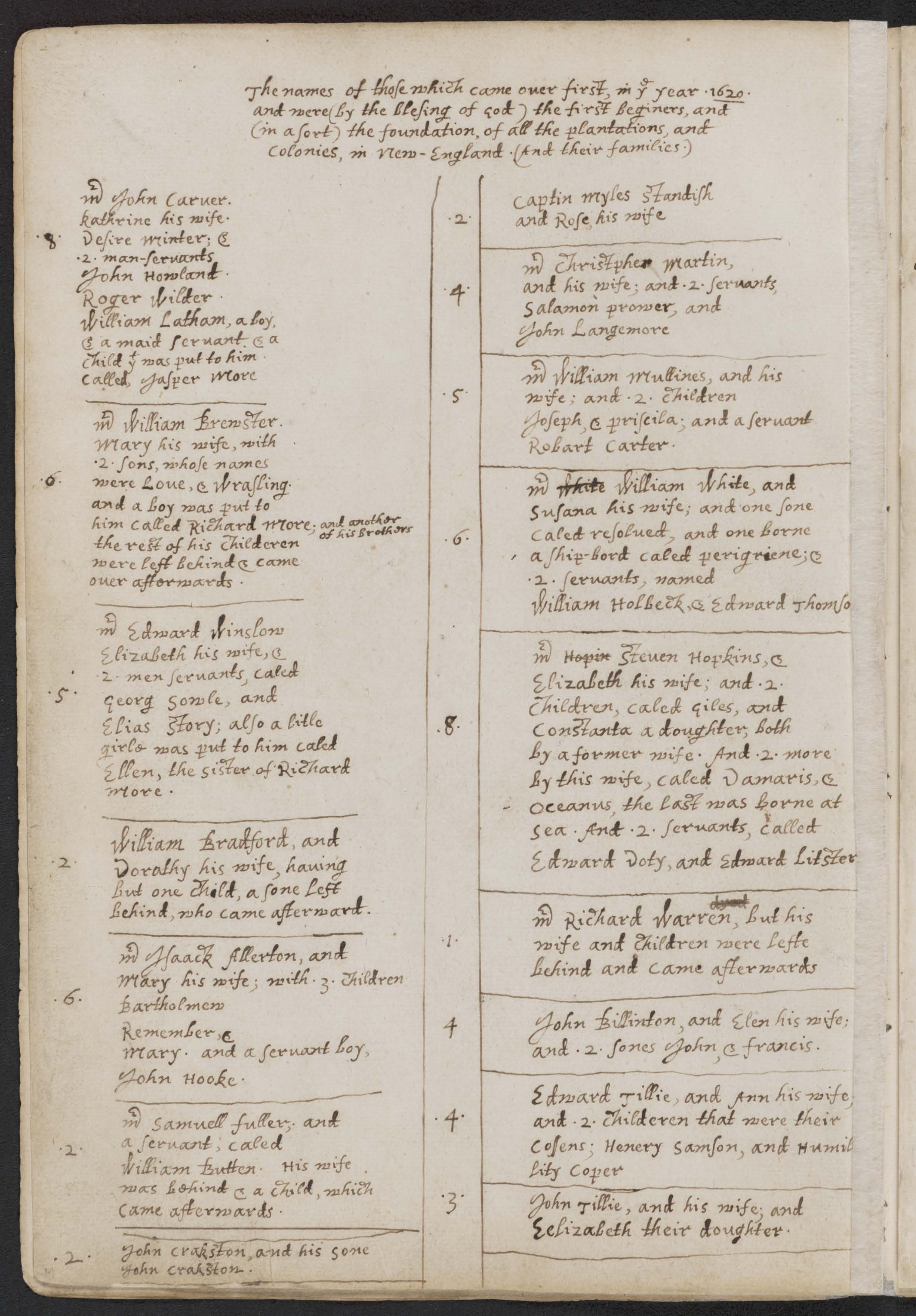

Extract from list of Mayflower passengers, from the Archive of the State Library of Massachusetts

These researchers have restored individual men, women and children to Mayflower history. They’ve also reminded us that while this is a story of departure and emigration, it is also one of arrival and immigration. More than that, the Mayflower is part of England’s history of colonisation too.

The passengers of the Mayflower were colonists. They made their new home in the territory of the Wampanoag. The ‘People of the First Light’ had lived in American’s eastern woodlands for over 12,000 years – and still live there today. For them, the passengers of the Mayflower were not just English arrivals. They were armed colonists, who would, with their descendants, dramatically change Wampanoag life forever. Indigenous Americans lost their land, their language and, in many cases, their lives. So, for the 5,000 Wampanoag people who still live on their ancestral land today, this colonial history is living history. It is also our shared history.

The Mayflower story has come to define England’s relationship with America. It has also shaped America’s view of itself. The Plymouth colony became Anglo-America’s place of origin and its settlers, over time, have become the originators of the idea of an immigrant nation. Some arrived before them, and many have arrived since. They have cultivated conflict, caused confusion and chaos, but they have also created communities and cohesion. All are part of the on-going transatlantic migration story.

This collaboration is part of Departures: 400 Years of Emigration from Britain – Partner Stories, a national series to accompany the Migration Museum’s Departures exhibition and podcast.

About the author: Jo Loosemore

Radio maker. History finder. Theatre lover. Jo is a broadcaster, curator and actor. For the BBC, she has created radio dramas, documentaries and live programmes. This has included World War One at Home (in partnership with the Imperial War Museums) for network and local radio, regional tv and online. From Brazil to the Battlefield, the story of Exeter fighting footballers was broadcast on BBC 5 Live, and a series of features appeared on BBC Radio 4 and 4Extra. She also produced the Listening Project’s national tour for BBC Radio 4, BBC Scotland, BBC Wales and BBC local radio in partnership with the British Library, contributing the 1000th conversation to the national collection. Having created the city’s oral history archive and co-curated Plymouth’s largest social history exhibition (Tales from the City), she is the curator of Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy – the national commemorative exhibition for 2020/21 in The Box, Plymouth, and co-curator of Wampum: Stories from the Shells of Native America, which toured nationally. She has also been recently appointed Visiting Fellow at the University of Plymouth.

Find out more about Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy at The Box Plymouth.