Emigration from Liverpool to Canada: the Street family story

Why did a family who emigrated to Canada from Liverpool in June 1924 return home just six months later – and what does their experience suggest about the reality of emigration for many British families?

This guest blog post by Megan Ashworth, Archive Assistant at Merseyside Maritime Museum, is part of Departures: 400 Years of Emigration from Britain – Partner Stories, a national series to accompany the Migration Museum’s Departures exhibition and podcast.

In the archive collections at the Merseyside Maritime Museum, one family’s story of emigration from the city stands out.

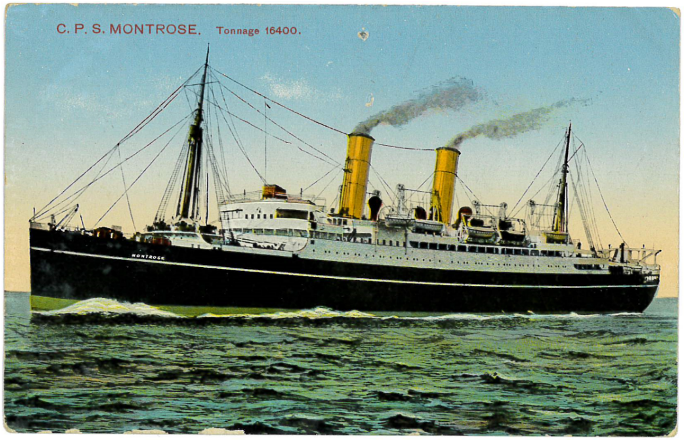

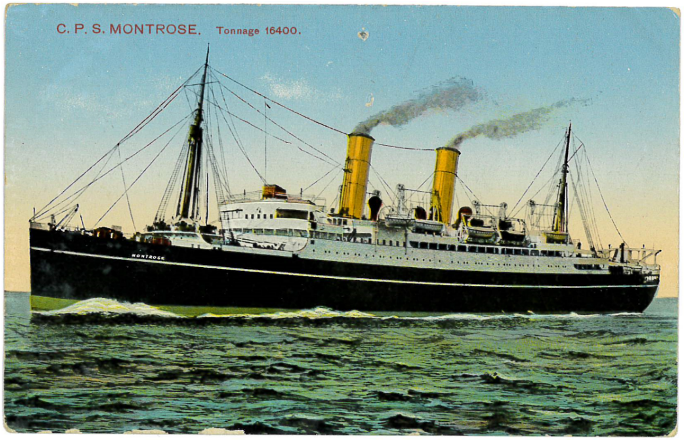

The Street family emigrated to Canada on board a Canadian Pacific ship in June 1924. But just six months later, they returned to Liverpool. The Canadian Pacific shipping line played an important role in promoting the promise of a new life across the Atlantic and facilitating these journeys. However, this life wasn’t always all it was set up to be – as the Streets found out…

A postcard of the Canadian Pacific ship the CPS Montrose, which the Street Family emigrated to Canada on board in June 1924, from the Merseyside Maritime Museum archive (Reference number: EVA/B/242)

Meet the Streets

The Street family consisted of three members: John and Ada and their two-year-old daughter Dorothy. The family lived in Oldham, then Lancashire, but decided to emigrate to Canada from the Port of Liverpool in June 1924.

They travelled as third-class passengers on the Canadian Pacific Montrose, and arrived in Quebec before settling in Toronto. However, just six months later in January 1925, the Street family returned to Liverpool on the Montclare due to homesickness.

In this display a New Year’s card which they received from loved ones only a few days before their return reads:

To our Ada and Jack,

From Ma, Pa, Frank and Dora

To wish you a Bright and

Happy New Year

across the world,

O’ersea and Land

I stretch out a loving hand

Their longing to return to Lancashire demonstrates that emigrant life was perhaps not quite as some had imagined. Their story therefore provides evidence that stands in contrast to the idyllic advertisements created by Canadian Pacific to encourage Britons to emigrate.

Liverpool: gateway to the world for millions of emigrants

On both their outbound and return voyages the Street family travelled on Canadian Pacific ships, a journey which took between 7 to 10 days from Liverpool.

Before their travels in the 1920s, Liverpool had already been established as the most significant port for emigration in Britain, with more than 12 million emigrants passing through Liverpool between the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The landing stage at Liverpool port around the time of the Street Family’s voyages. Courtesy of Peel Archives (MDHB Archive at National Museums Liverpool, Maritime Museum, MDHB/PHO/1360)

Initially, guidebooks were published to provide advice to prospective emigrants about work, customs and climate in the countries soon to be called home. In this particular guide to Canadian life, the advantages of Canada over the United States, a more popular destination for emigrants at the time, are emphasised:

“What we desire is that the advantages of Canada should be known, so as to induce men to weigh them as compared with the United States.”

Later, however, with the rise of steamships from the 1860s onwards and amid increasing competition between shipping companies to attract custom, it became part of their role to provide information to potential emigrants. Canadian Pacific used bright graphic designs, depicting both voyage and settlement, in their posters and brochures to encourage people to choose their company.

In particular, the shipping line presented images of picturesque farm scenes in an attempt to grow Canada’s farming population to work the land of the Manitoba and Northwest Territories, which they called “the granary of the world”.

So, it was in Canadian Pacific’s best interests to produce publicity that was as persuasive as possible in order to bring over people to farm the country’s land and work on its infrastructure, most notably the railways. The company stated that in the decade following the end of the First World War in 1918, more than 55,000 families settled on Canadian soil.

Promotion versus reality

The Street family’s voyages with Canadian Pacific highlight that the promotion of life overseas wasn’t always reflected in the lived experience of the passengers.

While many people chose to emigrate in hope of a better life and the opportunity to own their own land, some soon realised that emigrant life was not quite as they had imagined, and homesickness prompted them to return.

For these families, the rhetoric used by shipping companies to sell tickets didn’t always match up to reality – as the Street family discovered.

Sources and further reading

Marc H. Choko. 2015. Canadian Pacific: Creating a Brand, Building a Nation. Callisto.

John Herson. 2008. Liverpool as a Diasporic City. Working papers 8012, Economic History Society.

Written by Megan Ashworth, Archive Assistant at Merseyside Maritime Museum. This blog post is based on records which are part of the collections held at The Archives Centre.

This collaboration is part of Departures: 400 Years of Emigration from Britain – Partner Stories, a national series to accompany the Migration Museum’s Departures exhibition and podcast.