17 June, 2015

This blog on the subject of boat people, written by Migration Museum Project trustee Jill Rutter, is timely for a number of reasons. First, it is published in Refugee Week, when the UK’s attention is focused on the predicament of refugees. This year, Refugee Week is celebrating the contribution of refugees to the UK. (For an inspiring story on the current Mediterranean refugee situation, listen to Regina Catrambone – an Italian millionaire who set up Migrants Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) – talking on Tuesday 16 June’s Today programme – she is interviewed at 7.50am, 1 hour 52 minutes and 58 seconds in. MOAS’s ship, MY Phoenix, last year rescued 3,000 people in a three-month period alone.) Another reason this blog is so timely is that it coincides with a new venture which we are involved in at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, and for which the International Maritime Organization (see below in Jill’s blog) has created three short films, focusing on the migrants’ view, the captain’s view and the law of the sea. Each film – in the form of vox pops with a range of people visiting the museum, followed by facts and footage shot by IMO – is between two and three minutes long.

Over the last month or so the world’s media have highlighted the plight of boat people risking their lives in an attempt to reach safety in Europe and South-East Asia. We have seen pitiful images of Rohingya Muslims fleeing Burma, and of migrants rescued from the Mediterranean.

Since the late 1990s, migrants from the Middle East, South Asia, the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa have been using people smugglers to transport them across the Mediterranean. Ten years ago, Spain was a popular destination for these people, with over-crowded boats setting off in its direction from Senegal and Morocco. Today, migration flows have moved east, with boats now leaving Turkey, Egypt and Libya, and making for Greece and Italy. But the factors that drive people to entrust their lives to people smugglers remain the same: persecution and threats to life, worklessness and the belief that Europe offers a route out of poverty.

Gateway to Lampedusa – Gateway to Europe, a memorial by the Italian artist Mimmo Paladino

Antigua cemetery in Fuenteventura, Canary Islands with named and unnamed memorial tablets for migrants who have drowned. The image is by the acclaimed Juan Medina who has been photographing migrants for nearly 20 years.

Nobody knows how many migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean. The International Organisation for Migration estimates 1,700 people have lost their lives this year and as many as 14,600 since 1993. This is almost certainly an underestimate, as the tally is based on retrieved bodies. We will never know the real number of deaths and many of the sea victims remain nameless, as is evident from the memorials to them in Spain and Italy.

Many people in Britain have been shocked by recent events, but the plight of the Mediterranean boat migrants can seem distant. Save for small numbers of Afghans, relatively few Mediterranean boat migrants now make it to Britain. Migration by sea may have been the usual route for most migrants coming to or leaving the UK until relatively recently, but almost all of them used the services of passenger shipping companies, rather than people smugglers.

One exception was Vietnamese refugees, most of whom arrived in Britain by way of camps in Hong Kong. Between 1979 and 1992 the British government admitted about 24,500 Vietnamese refugees, most of whom had left Vietnam in a sea-borne exodus of over 800,000 people. Setting off in small boats, they made for other South-East Asian countries, including Hong Kong. In journeys that could take many weeks, the boat people had to contend with thirst, storms and piracy. Estimates of the numbers who died at sea can only be guessed at, but the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees suggests that between 200,000 and 400,000 Vietnamese lost their lives at sea. South London and East London are now hubs for this community. The testimony of those who survived these journeys has been collected in a number of oral history projects.

Vietnamese refugees, 1979

Looking back further into British history, there are two other noteworthy arrivals of boat migrants. About 60,000 Protestant Huguenots and Walloons arrived by boat between 1550 and 1720 – a highly skilled group whose numbers included silversmiths, silk weavers and bankers.

A rescue is mounted for the ‘Poor Palatine’ boats

Between May and November 1709 about 13,000 impoverished ‘Poor Palatines’ crossed the North Sea in overloaded boats. The Nine Years War (1688–97) and the War of Spanish Succession (1701–14), followed by a series of harsh winters and poor harvests, had created severe hardship in much of south-west Germany. Setting sail from Rotterdam in overladen boats, the migrants were, on arrival in Britain, initially sheltered in army tents on Blackheath and Camberwell in London. The Poor Palatines were mostly unskilled labourers and the failure to integrate them proved politically controversial. Most were eventually resettled in Ireland and North America, where their descendants included the Rockefeller family.

There is another and less well-known connection this country has with boat migrants: Britain has been at the forefront in developing international humanitarian law about the safety of life at sea. It was the first state to join the UN’s Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization, the previous name of today’s International Maritime Organization (IMO). Set up in 1949, the IMO has had its headquarters in London since 1959, first of all in Chancery Lane and then, since 1982, on the Albert Embankment. The IMO sees that international treaties and regulations on shipping are observed, including those relating to rescue at sea. The International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, signed in 1979, requires that ‘Parties shall ensure that assistance be provided to any person in distress at sea … regardless of the nationality or status of such a person or the circumstances in which that person is found.’ In the same document, ‘rescue’ is defined as ‘An operation to retrieve persons in distress, provide for their initial medical or other needs, and deliver them to a place of safety.’

The IMO’s first headquarters in Chancery Lane, London.

Although treaties on shipping pre-date the founding of the United Nations (UN), the IMO is part of the UN family. Two of its former secretary-generals have been British, and much of the IMO’s work on maritime search and rescue was taken forward by British staff.

Today in the Mediterranean, the Royal Navy’s HMS Bulwark is part of Europe’s search-and-rescue mission. But, as the migrants are brought to safety, we should remember that boat people are not a new phenomenon – either as far as Britain is concerned or for the world as a whole.

Jill Rutter is a trustee of the Migration Museum Project.

9 June, 2015

In this Guest Blog, Sue McAlpine, freelance curator with the Migration Museum Project, gives us an insight into her Keepsakes experience.

When the Migration Museum Project asked me earlier this year to curate their Keepsakes exhibition – I had previously curated 100 Images of Migration at Hackney Museum in 2013, the first time that particular exhibition had been displayed – I jumped at the chance. I felt it chimed well with the work I had been doing at Hackney collecting people’s stories and objects. Everybody has a keepsake and a story to tell, I think, and I love hearing those stories – even more, I love giving people an opportunity to have their voices heard so that they can feel proud of their culture, share it with others and pass it on to their children. Keepsakes seemed a perfect way to do this.

Our guest blogger Sue McAlpine celebrating the launch of 100 Images of Migration at Hackney Museum in 2013. © Migration Museum Project

But collecting keepsakes turned out to be very different from collecting objects destined to end up in a museum, displayed for a time in a case and then wrapped in tissue paper and kept in an archival box in a museum store. The process of meeting the contributors, finding the keepsakes and hearing the stories seemed more personal and intimate. I liked the fact that these objects had a life of their own beyond being simply museum objects.

![2a Keepsakes contributors at Southbank Centre [Colour+Full]](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2a-Keepsakes-contributors-at-Southbank-Centre-Colour-Full1.jpg)

Keepsakes contributors share their keepsake stories at a celebration event at Southbank Centre on 2 May 2015. L–R Robert Winder (MMP Trustee and discussion chair), Maurice Nwokeji, Henning Wehn, Sajeela Kershi (honorary guest), Alishah Akram. © Migration Museum Project

What do we mean by the word ‘keepsake’? A keepsake is a very special thing that we keep to remind us of a person, or a place or a memory. It might have travelled with us in a suitcase from another country; we might have found it here; it might have been passed down through generations in the family. And, in a key difference from other museum objects, keepsakes are only loaned: once the exhibition they are part of is over, they are no longer part of the museum’s collection. The keepsakes that we have displayed at the Southbank Centre, for example, as part of the Adopting Britain exhibition in London’s Royal Festival Hall, will return to their owners once the exhibition is over, to continue their journey.

Keepsakes display in the Adopting Britain exhibition at Southbank Centre. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams.

I travelled to Peru in 1976 and bought a soft alpaca baby’s hat, which my son wore when he was born a year later. I still have it and, as part of our Keepsakes work with communities, took it to show a group of Latin American women in South London. Although it’s personal to me, it belongs to their culture. One of the Peruvian women, Celeste, quietly mended the holes in the hat, so now my keepsake has another chapter to its story. Who knows what its future might be? Perhaps keeping warm the tiny head of a future grandchild.

Celeste mends Sue’s Keepsake – a Peruvian hat her son wore as a baby. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Sue McAlpine.

Many migrants or refugees have suffered pain and loss: they may have escaped war or persecution in their own countries and, for many reasons, find it hard to put their story into words. It’s too raw. Many people don’t necessarily want to be identified by their story. But talking about a keepsake seems freer and easier.

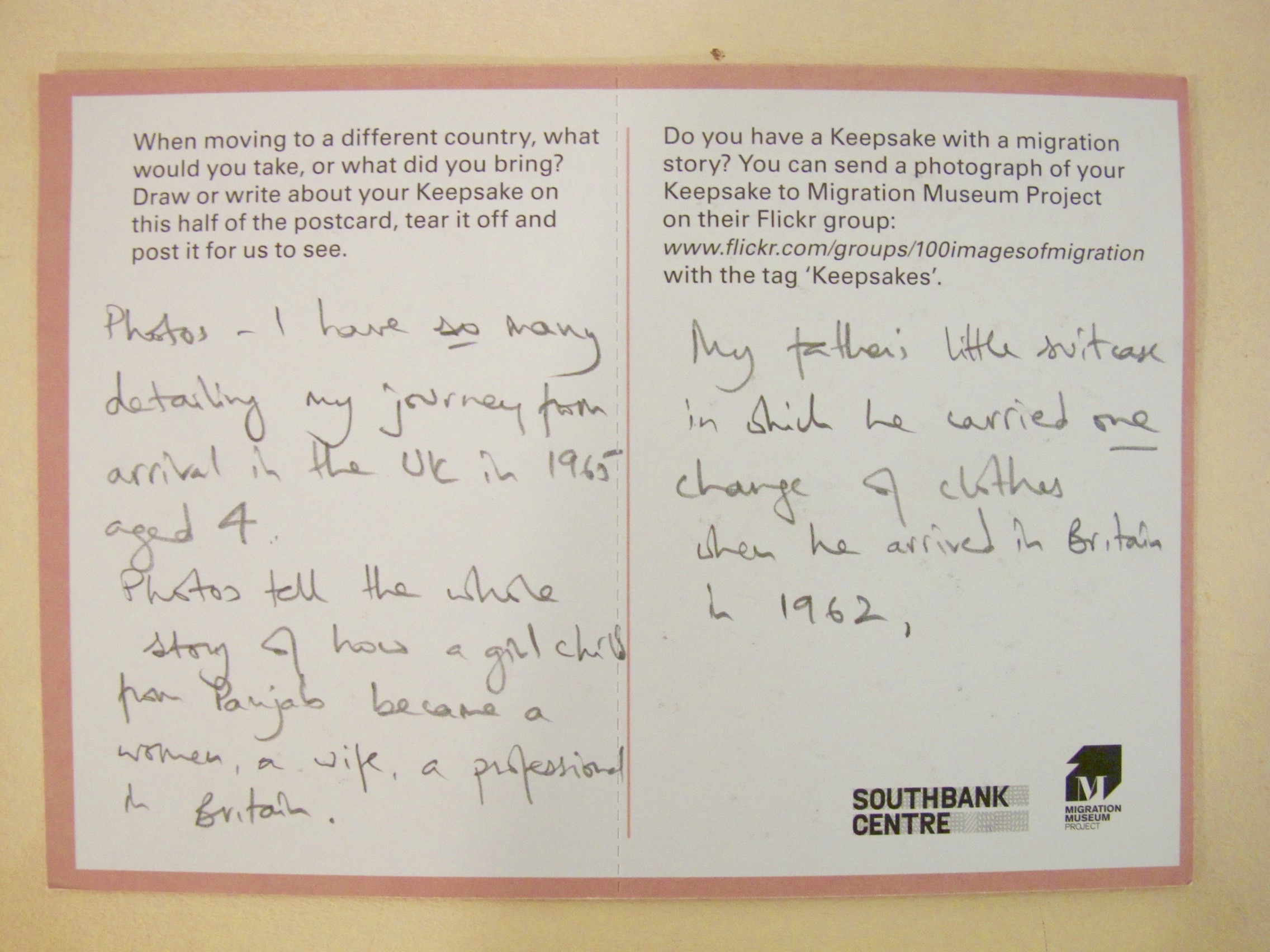

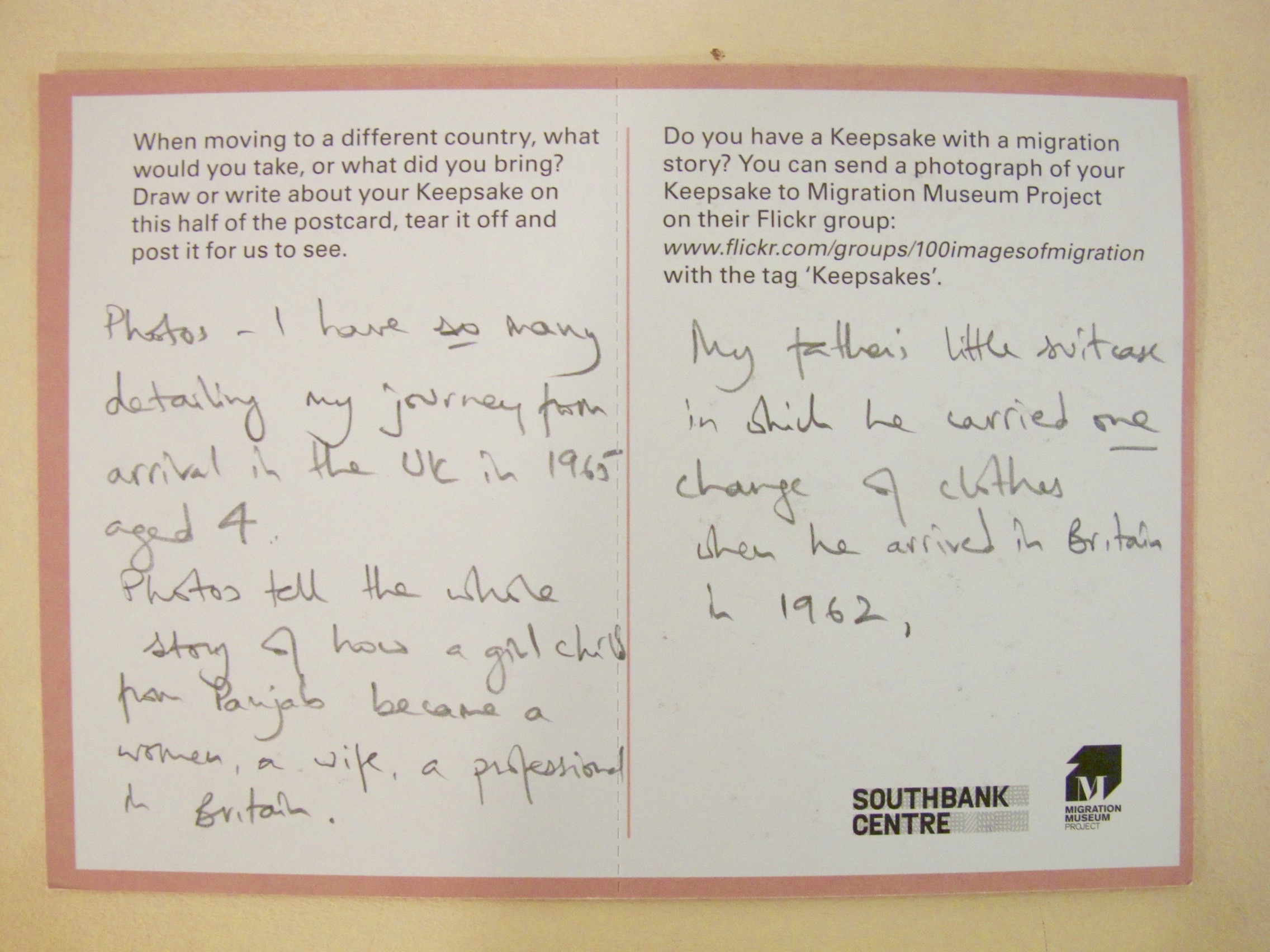

Keepsakes postcard – a visitor to Adopting Britain shares a little about her family keepsakes, just hinting at the depth of stories behind them. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams

I’ve known Maurice Nkoweji for some time. In 1970, he was a child in Nigeria, starving in the famine caused by the Biafran war. He and his younger brother – little boys who then knew only war and hunger – were rescued and came to this country with the Red Cross. I asked Maurice to contribute a keepsake for this exhibition and he gave me an Ekwe, a musical instrument made from a tree trunk (you can find out more about the Ekwe in Maurice’s description). He wanted to show something that reminded him of his Igbo culture and tradition in happier times. You can see a short clip of Maurice performing with his Afrobeat reggae band One Jah here, and you can watch Maurice talking about his Ekwe and arrival in Britain in this London Live TV clip.

Maurice’s Ekwe photographed by Keepsakes photographer Camilla before moving into its temporary home in the Adopting Britain Keepsakes display. © Camilla Greenwell

Anna Hegarty lent a tiny metal reindeer that comes from Lapland and travels with her everywhere she goes. In crowded cities it reminds Anna of the wide, open spaces of her own country.

Anna’s reindeer in its temporary home – the Keepsakes display in the Adopting Britain exhibition. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams.

Sasha Zavjalova’s Georgian metal plate with its stylised head of a young woman helps her to imagine the mysterious land where her grandparents grew up. During the Stalinist repressions, they were forced to leave their homeland and went to live in Soviet Estonia. When Sasha came to live in Britain seven years ago, the plate came with her, continuing its own migratory journey.

Sasha’s metal Georgian plate in the Adopting Britain Keepsakes display. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams

We want to continue this lovely project. We were able to show only a few keepsakes in the exhibition in London’s Southbank Centre, so we are now sharing more stories and more keepsakes with communities in South London. It’s an exciting project that’s living up to the initial high hopes I had for it. Every new engagement throws up new and exciting discoveries, so watch this space!

FULA (Latin American Elders) Keepsakes session. Marta brought in traditional Argentian maté gourd cups and silver straws which have been passed down from generation to generation in her family. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Sue McAlpine.

Sue McAlpine is currently freelancing as a curator, working especially in community engagement in museums. She joined Hackney Museum in 2006 curating exhibitions, managing collections and working closely with Hackney’s communities. Working backwards, before Hackney she worked in Notting Hill as a carnivalist, oral historian, exhibition designer and community historian; in 1990 she established an education service at Gunnersbury Park Museum and she was education officer at the Museum of London from 1977. Having curated the first showing of 100 Images of Migration at Hackney Museum, Sue has continued her involvement with the Migration Museum Project (of which she is a distinguished friend) and was the principal curator for the Keepsakes exhibition: a prototype of this exhibition is currently on view at the Southbank Centre, as part of the Adopting Britain exhibition.

9 May, 2015

‘Photo man’ Tim Smith – a contributor to 100 Images of Migration – looks back on 30 years of looking in on other people’s lives

Dolphin Street consists of 200 metres of unremarkable two-up, two-down terraces in Newport, South Wales. I moved there in 1982 because the rent was cheap, and I’d enrolled to study documentary photography at the local college of art. I was excited by the possibilities that the course offered, but unimpressed with my new surroundings next to the muddy River Usk. Overlooked by a large Victorian primary school, Dolphin Street’s most notable features were the pub that sat on the corner with the main drag down to the nearby docks, and the Yemeni café next door.

A young Yemeni girl at school assembly in the docklands area of Newport, 1982.

It was the best move I ever made. The dockland area was full of rows of outwardly nondescript streets similar to mine, but home to people with extraordinary life stories that connected Newport to the rest of the world. Local coal had once fuelled ships ferrying cargo all over the globe, with crews hired in Kingston and Karachi, Aden and Bombay. Once docked in Newport, many sailors had to find a new ship to work on, and between voyages they stayed in boarding houses, such as the rooms above the Yemeni café. Some also found jobs ashore, and were later joined by their families. My neighbours in Dolphin Street included several Yemeni families, as well as people from islands across the Caribbean, from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Mauritius and China, as well as the Welsh, Scots and Irish. A houseful of English students was hardly noticed.

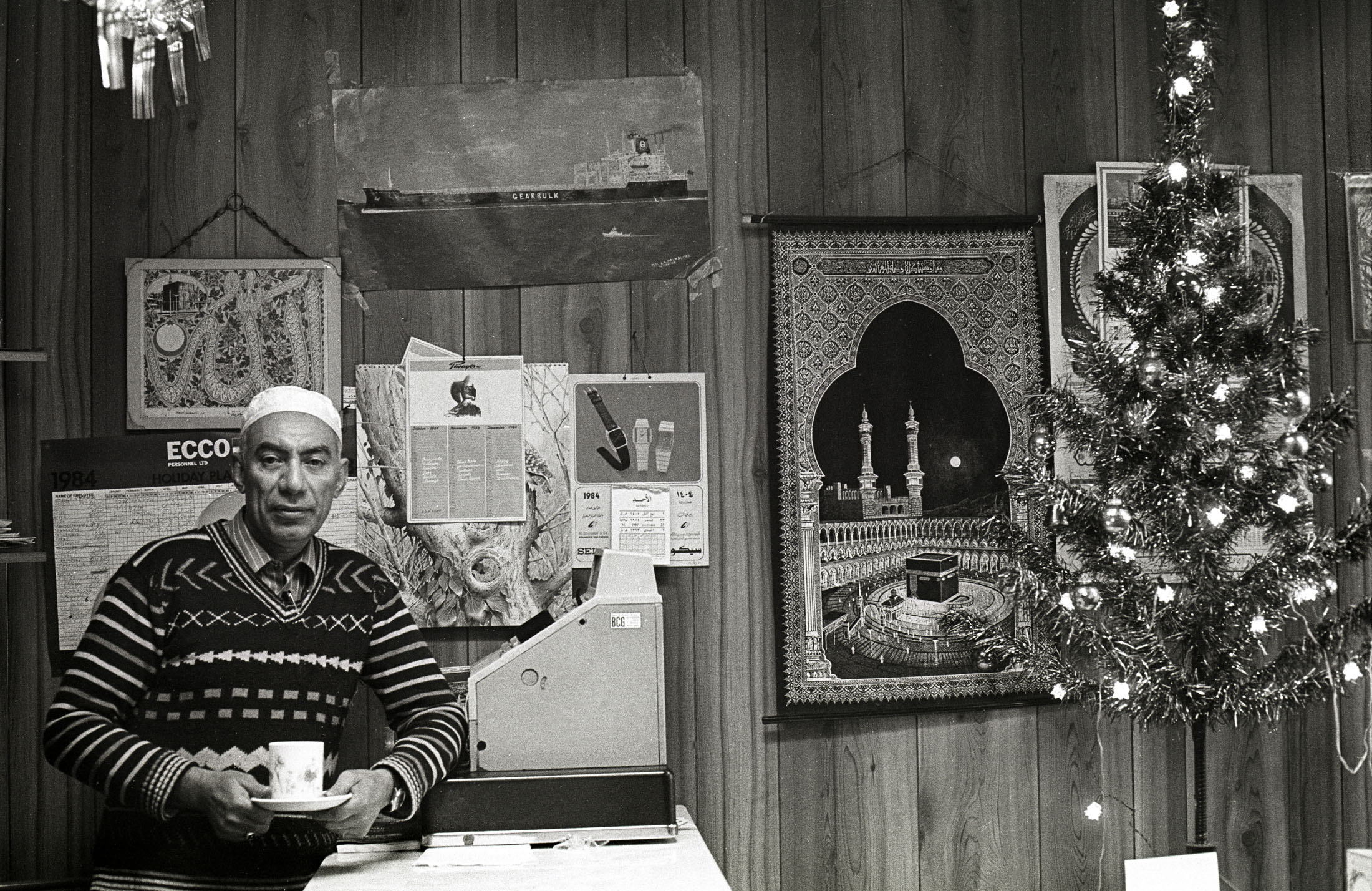

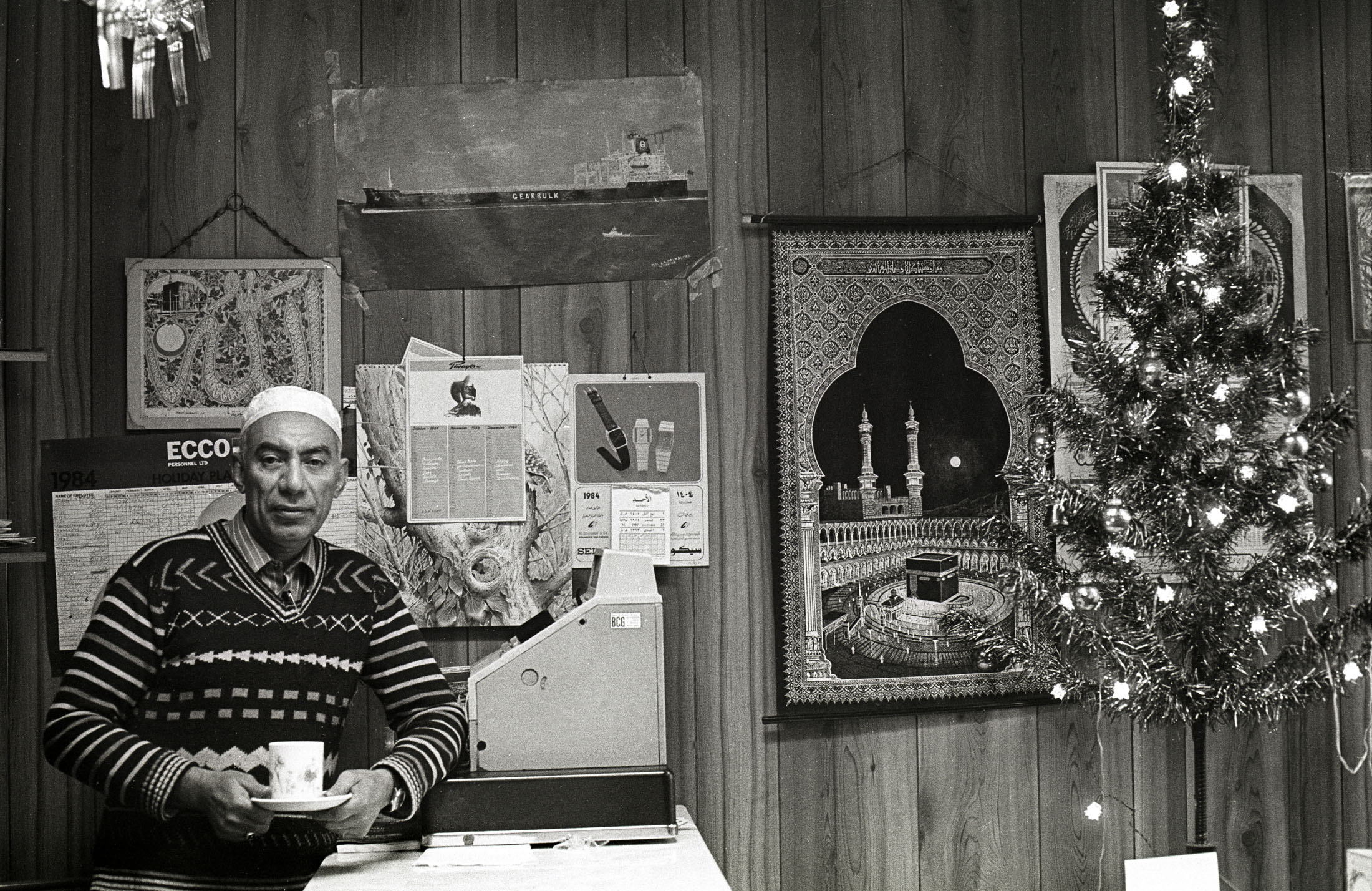

Yemeni café owner in the dockland area of Newport. He provided food and board to Yemeni sailors working on ships carrying Welsh coal to Aden. Until its independence in 1967, Aden was part of the British Empire, serving as a huge bunkering station to fuel British ships sailing to Bombay and beyond, 1982.

College taught me that good photography is very often about good access. I started taking photos in the school, the pub and the café, and I discovered that free prints acted as a backstage pass to people’s everyday lives. I was invited (or sometimes invited myself) to weddings, birthdays and BBQs. Kids along the street called me the ‘photo man’, and in some households I became just part of the furniture. Getting access to the ordinary offered the most extraordinary opportunities for me in my early attempts to make interesting photographs.

Drinkers at the Commercial Inn on Dolphin Street.

A British Pakistani man working in a Bradford spinning mill during the 1980s.

I left Newport in 1984 with a set of pictures shot on Dolphin Street that formed my first ever exhibition, held at the Commonwealth Institute in London. This portfolio also landed me a job in Bradford, working for the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit, which used photography and oral history to produce exhibitions and publications that reflected the lives of local people. Bradford was once the wool textiles capital of the world and many of the communities that had come to the city from overseas, such as those from the Asian sub-continent, were familiar to me from my days in Newport. Others – such as the Poles, the Ukrainians and the Italians – presented a new set of stories to be told.

The DJ Radical Sista hosting a ‘day-timer’ in a Bradford nightclub during the heyday of these music events in the 1990s. Day-timers were held in the afternoons for Asian teenagers who may not have been allowed out during the evenings.

More than thirty years later I’m still based in Bradford, and exploring stories of migration remains a recurring theme for me. I’m fascinated by individual life stories that often depend on chance and circumstance, but are also shaped by the broad sweep of world affairs. The international networks created via trade and the British Empire, the Second World War, the Partition of British India and the break-up of the Soviet Union are a few examples of global events that have had a profound effect on Bradford’s cosmopolitan communities, and on modern-day Britain.

In the run-up to Ukraine’s declaration of independence in 1991 the streets of Kiev were crowded with people engaged in political debate. This man is making a point to supporters of the old Communist order by brandishing a picture of himself as a young man taken shortly before he, along with millions of other Ukrainians, had been sent to Stalin’s labour camps.

The ambition of much of my work is to weave together the historical narrative with personal stories, while exploring connections between Britain and the rest of the world. Photography, oral history and film making are great tools for this, and act as my passport. I’ve had the privilege of meeting many remarkable people who have shared their stories and those of their communities, both here and overseas. Conversations started in Britain have often been continued in eastern Europe; on islands across the Caribbean; in west Africa, east Africa; and in India, Pakistan and Yemen.

The former Post Office on the seafront at Roseau, capital of Dominica. This island is the original home of the majority of Bradford’s Caribbean community.

My most recent journey took me to Gujarat and Mumbai, an area from which around 50 per cent of the British Indian community originates. The resulting exhibition, India’s Gateway, explores the history of Gujarat and Mumbai as age-old centres of global trade and migration, and focuses on the region’s remarkable relationship with Britain.

Staff at the Britannia and Co, an ‘Irani café’ in the genteel Ballard Estate business district of Mumbai. Established by Parsis – Zoroastrian immigrants from Iran – during the days of the Raj, there were once almost four hundred such cafés. Now, fewer than thirty remain.

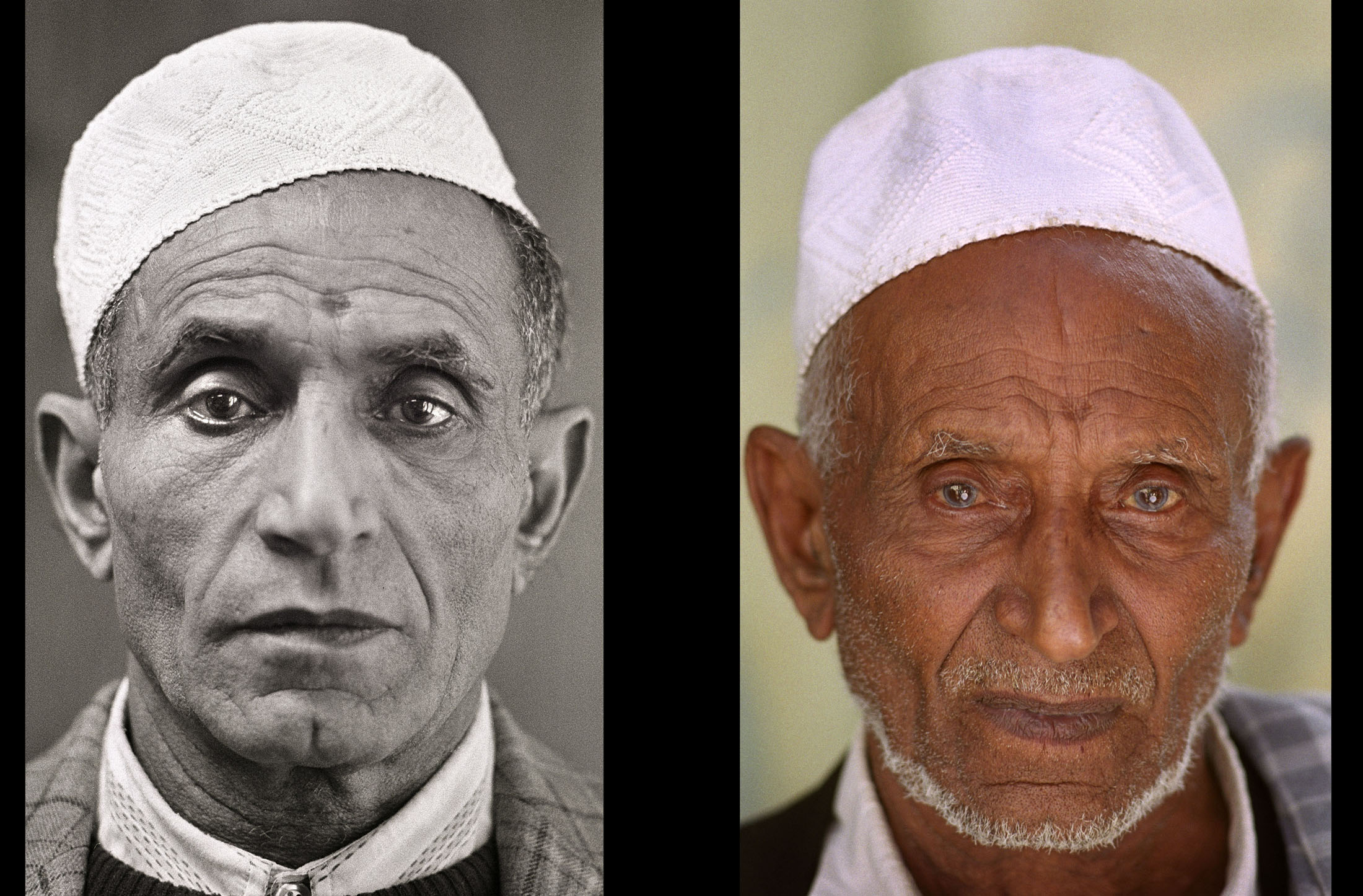

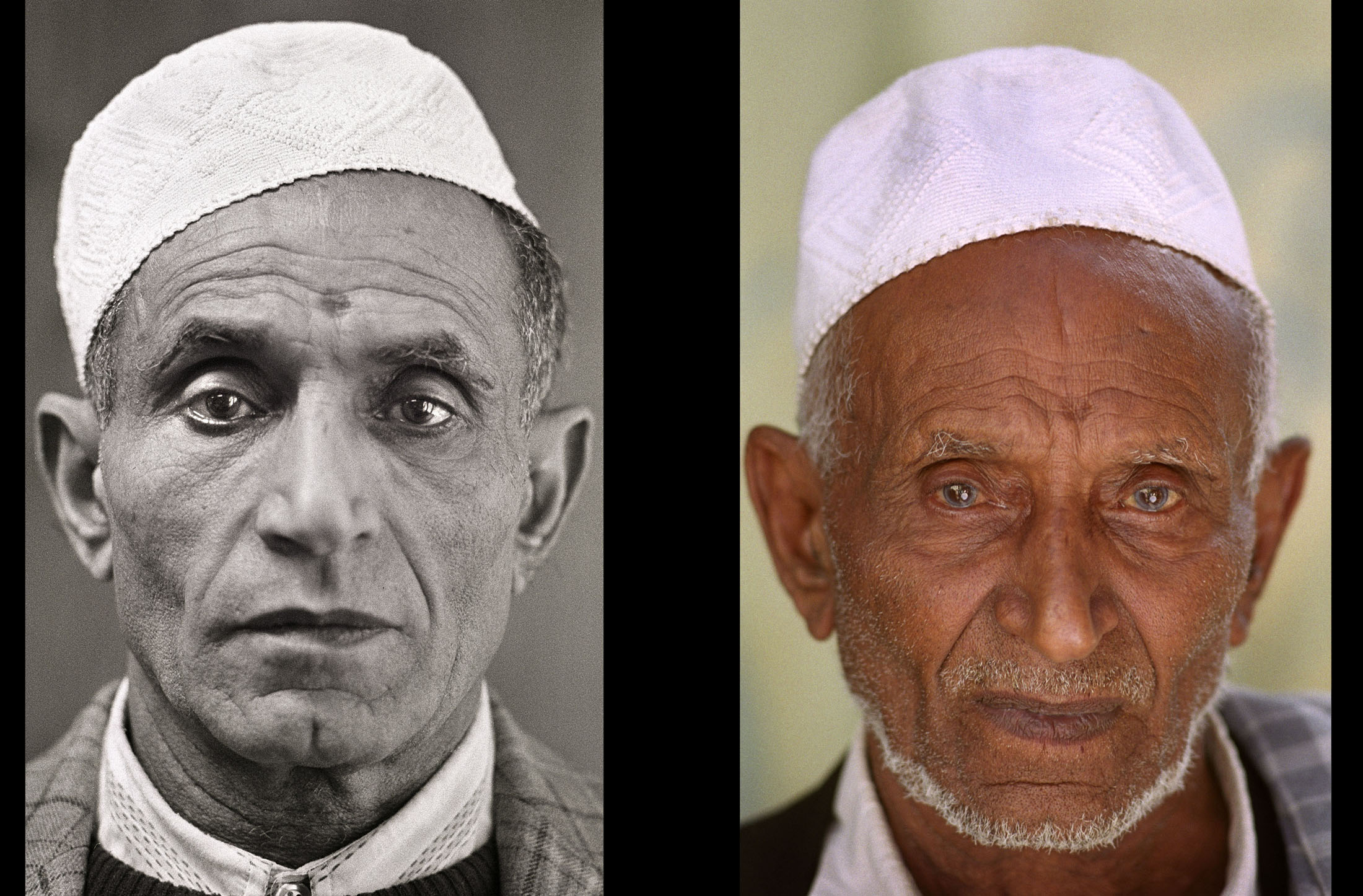

I’ve also made several trips to Yemen to make the photographs for a book called Coal, Frankincense and Myrrh: Yemen & British Yemenis. In the course of my journeys seeking out former sailors, steel workers and shop keepers – many of whom have retired home to a string of villages just north of Aden – I had a chance roadside meeting with Fayed Ali. I’d first photographed him in the café in Newport in 1982. It was great to catch up with him over a cup of tea and talk about the town that neither of us had visited for over a decade. That conversation rekindled my curiosity about Dolphin Street. During a recent trip to Wales I went back, to discover that the Yemeni café is now a Czech-run mini-market. The migration story moves on, and much work remains to be done!

Fayed Ali, a former sailor who first arrived in Britain in 1948. He worked for British Rail for many years, manning trains on the Swansea to Newcastle line before retiring to Yemen in 1993.

The Polish band Wilki on stage in front of 12,000 young Poles who filled Wembley Arena for London Live, billed as the largest Polish music festival ever held outside Poland. 2008.

Notes

If you are interested in seeing India’s Gateway – which tours to London, Leicester, Kirklees, Bradford and Blackburn between July 2015 and July 2017 – please e-mail Tim.

For information on Tim’s books on Yemen, Ukraine, the Grand Trunk Road and Asians in Britain see here.

http://www.timsmithphotos.com

![2a Keepsakes contributors at Southbank Centre [Colour+Full]](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2a-Keepsakes-contributors-at-Southbank-Centre-Colour-Full1.jpg)