Archives

1 July, 2016

One of the more unpleasant effects of the referendum result has been a spike in anti-immigrant activity, with abuse hurled at Poles in the street and graffiti daubed on cultural centres run for and by EU migrants. This change in atmosphere, allied to the uncertainty of their future status in a UK divorced from the EU, has led to understandable anxiety among immigrants from other EU countries. In this guest blog, taken from his Free Movement blog, Colin Yeo sets out the legal consequences of last week’s momentous decision. Colin recently took part in our panel discussion on ‘The Ethics of People Smuggling’, one of the activities run as part of our recent Call Me By My Name exhibition in Shoreditch, London.

What next?

The people of what is currently the United Kingdom have voted to leave the European Union. What happens now? Here I am going to take a quick look at the immediate consequences for EU nationals living in the UK.

In short, there are no immediate legal consequences that flow directly from the referendum result. The law of the United Kingdom only changes when Parliament enacts a new law through the full Parliamentary process and no such law has been passed. David Cameron, who is stepping down as Prime Minister, has stated that he will not immediately trigger Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, so there will be no immediate change to free movement laws either.

The longer answer is that we just do not know what will happen in the weeks and months ahead.

Even before the referendum on 23 June some advertisements – such as this deliberately provocative ad put out by Operation Black Vote – were being criticised for focusing on immigration in a way that was bound to incite animosity.

The Immigration Law Practioners Association put together a series of briefings on different Brexit issues which may be of interest. These are largely speculative, though: no one knows what is going to happen now.

If the new Prime Minister does trigger Article 50, then the UK will leave the EU within a two-year period and will at the point of leaving cease to be subject to EU law, including free movement law.

There is some optimistic talk of Article 50 not being triggered and instead a further renegotiation taking place, and perhaps another referendum. That seems politically very unlikely, and it is hard to see how internal Conservative Party politics would allow for such an eventuality. With the pound plummeting, UK government debts to be downgraded, Scotland to demand a further referendum and perhaps with an exodus of big employers to be announced, I guess the politics may change as people realise what they have done to themselves and their country. But I seriously doubt it. It is done.

It seems certain that some generous provision will be made for EU nationals currently resident in the UK.

There was some talk during the campaign of EU nationals automatically retaining “acquired rights” under the Vienna Convention of 1969. That sounds like legal nonsense to me and Professor Steve Peers seems to think so too. Some specific legal provision will need to be made under UK law in my view. If the Government has any decency and any sense, an announcement on this will be made very quickly.

In the week following the referendum, there had been a five-fold increase in the number of hate crime incidents reported to the National Police Chiefs Council (as of Thursday 30 June).

It seems certain that some generous provision will be made for EU nationals currently resident in the UK. There are around 3 million EU nationals living here, all of whom would need a new immigration status. Many of them do not have residence documents because under EU law residence documents are optional for EU nationals and their family members.

My best guess is that free movement laws would be incorporated into UK law. At the very least this would apply to those who are already resident in the UK as at a certain date. The law would take effect automatically without anyone having to make an application as such. On a sliding scale of ever worse possibilities, the existing rules might be tweaked to make it harder to qualify for settlement and easier to deport, family members of EU nationals might not be treated as generously as EU nationals themselves or, worst case, all 3 million EU nationals would suddenly be required to make new applications under UK immigration laws. This last possibility seems extremely unlikely.

The UK may end up staying in the European Economic Area, like Norway, in which case free movement laws would continue to apply as they do today, including for future residents from the EU. However, given that immigration seemed to be the decisive issue in the referendum — much to our collective shame — joining the EEA seems like the worse of all options, as it would mean continued free movement rules but also continued payments into the EU and no control over the rules to which the UK was signed up.

There is widespread concern that the referendum result appears to have legitimised racist activity.

In the meantime, many EU national residents will be extremely concerned about their position. Family members of EU nationals may be even more concerned. Many will want to apply for residence documents, for permanent residence and for naturalisation as British. I’ve previously written blog posts which may be helpful (all of those below are up to date) and also put together an ebook guide on making EU free movement applications.

On a personal level, let me end this piece by saying how sorry I am to any EU national readers. I am sorry that our country has put you in this position. The vote is an awful, terrible result not just for the UK but for Europe and I am so desperately sad at the outcome and what it says about us.

Other blogs on residence applications by Colin Yeo

How to make a permanent residence application

Home Office confirms that official EEA series application forms are not necessary

Waiting times for EEA residence applications

Expediting an EU residence document application

EU nationals must apply for permanent residence card for British nationality applications

Colin Yeo is a barrister specialising in immigration at Garden Court Chambers who recently took part in our panel discussion on ‘The Ethics of People Smuggling’. This blog was first posted on his Free Movement blog, the widely respected blog on immigration law.

6 July, 2017

I left Afghanistan because the situation wasn’t good. The main reason was the war and the Taliban. People had to leave because of the problem, the politics thing. It’s not very easy to leave. The first thing is you don’t want to leave your country but if the situation comes to you, you have to leave – you leave everything behind – your family, your country, you just go – to a kind of survival, to get away from the troubles, that’s what it was all about – you can’t imagine how hard it is.

There’s excitement in the market – you see lots of people coming and going. Of course it’s hard work but the excitement is there and sometimes it takes the tiredness away from you.

8 June, 2016

This guest blog is written by Rob Pinney, one of the photographers who submitted photos for our exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond, which is at 28 Redchurch Road, London, until 22 June (details here). Rob’s book, The Jungle, is on sale at the exhibition and from his website (see below) with all profits going to charities working in Calais.

A complex relationship in a complex place

Grocery Store, November 2015. Shops like this provide, among other things, basic food staples and mobile phone credit top-ups, incredibly important for keeping in touch with family both at home and often at different stages of the refugee ‘trail’ through Europe. Many people in the ‘Jungle’ report having been victimised and attacked by both the police and ordinary citizens when outside the camp, and so feel unsafe walking into Calais to use local shops. This particular shop was destroyed in March 2016 as part of the eviction and demolition of the southern half of the camp. © Rob Pinney

As the main point of departure for sea and rail travel to Britain, the coastal town of Calais in northern France has become a ‘hotspot’ for asylum seekers hoping to build a new life in the United Kingdom.

‘The Jungle’ — the term used to refer to the shanty town settlements that have become synonymous with Calais — has no fixed location. But it is most commonly associated with a former landfill site not far from the ferry port that at its peak during the 2015 refugee crisis held a population of some 8,000 people.

The political discourse around the jungle and those temporarily seeking shelter there thrives on generalisations. Labelled a ‘swarm’ and a ‘bunch of migrants’ by British Prime Minister David Cameron, in the eyes of many the people here are not individuals but a collective mass — the object of a confused war of words: ‘refugees’, ‘asylum seekers’, ‘economic migrants’.

The reality is far more complicated. Many have fled war and political persecution. Others, notably from Afghanistan and Iran, left to avoid being made to fight for a cause they did not believe in. Many will show you photographs on their mobile phones of family already living in the United Kingdom, whom they hope to join. And some have spent years, occasionally decades, living and working in the UK, only to find themselves suddenly ejected. For them, the journey is not one of migration but a return home.

‘What is it like?’, often asked, is a simple question that defies an equally straightforward answer. Unlike the epic photographs of Zaatari in Jordan, whose orderly lines of identical shelters extend outwards on a vast scale, the Jungle follows no such logic. The Jungle is a city. Alongside countless tents and shelters, nestled into any and all available space with little regard to order, stand shops, cafes, restaurants, hairdressers. While different nationalities have generally grouped themselves together — as is common in any city — these lines are also frequently transgressed by a shared political precarity that unites its citizens. But above all, the Jungle is a city that is constantly changing. Some of these changes are internal and organic, but others have been the result of more profound changes in the political landscape in which the Jungle is deeply embedded, and yet over which it holds no control.

While cameras are a common sight, they are treated with great suspicion. Many people are wary of being photographed: some fear it may endanger their families should news of their escape reach home; others worry that evidence of their presence in France may be used against them should they eventually claim asylum in Britain; and others still feel ashamed of the situation they now find themselves in and do not want it immortalised in any resulting pictures.

It is not difficult to create photographs that evoke misery and suffering in the Jungle. And while such pictures might fit with what we think documentary photography ought to look like, such images usually take recourse to particular visual tropes and do little to deepen public understanding of a complex place at a time when greater understanding is so sorely needed. At the same time, it would be wrong to beautify what remains an utterly deplorable situation that exists not out of necessity but because of broken politics.

The photographs presented here are drawn from a much larger collection that spans four trips over six months. This selection is tempered by conversations I have had with some of those who live there about photography and the representation of the Jungle in the media. One friend from Darfur lamented the way in which many photographers came simply to ‘make their own business’. While I hope that the time I have spent volunteering on each of these trips is sufficient in his eyes to keep me out of this category, I also hope that the images here are seen as ones that are sensitive and respectful towards the issues so frequently voiced by the Jungle’s people. There are no portraits, nor any identifiable faces. In their place, I have tried to show traces of the many lives that are now collectively on hold. The impression left may be one of a desolate, depopulated landscape. But the reality couldn’t be further from that: beyond the edges of each frame is a vibrant and dynamic city in the making.

Police Lines, March 2016. Eritrean men watch through police lines as their shelters are destroyed. Following the partial eviction that took place in January 2016, the authorities announced a more significant intervention two months later: the southern half of the camp was to be evicted and demolished. They estimated that this area contained 800–1,000 people, but a census conducted by charities working in the camp suggested the figure was as high as 3,500. Many of those who lost their homes chose to leave the ‘Jungle’ and retrace their steps, often heading back to Germany, where asylum policy is thought to be more lenient. But many others moved into the little remaining space in the northern half of the camp, condensing those from different communities ever closer together. © Rob Pinney

Mario’s, November 2015. Mario’s is one of a number of restaurants that used to line the mud road running through the southern half of the camp. Many of the owners were formerly child asylum seekers who had been granted leave to remain in the United Kingdom but who had to leave upon turning 18 years old. Many now have asylum in France and, in some cases, Italy, but continue to run their businesses in the ‘Jungle’. Mario, who owned the 3 Star Hotel, was given his name on account of his impressive moustache. The hotel was among the hundreds of makeshift restaurants, businesses and homes that were destroyed as part of the eviction and demolition of the southern half of the camp in March 2016. Since then, and as the number of newcomers has started to increase once more, many of the remaining restaurants have opened their doors to people hoping to avoid the bitter cold of a night spent in a tent. © Rob Pinney

Burning Shelter, March 2016. As the eviction of the southern half of the ‘Jungle’ gathered pace, fires set by refugees and the use of tear gas by French riot police became commonplace. In the UK, the media have woven the persistence of fires into a narrative of destruction and lawlessness. But you might also see it this way: the decision to put a match to the walls of their shelters is arguably the only way refugees were able to exert at least a degree of agency over the inevitable destruction of their homes. © Rob Pinney

Shipping Container, January 2016. In January 2016, French authorities announced that they were going to clear a 100-metre ‘buffer zone’ between the edge of the camp and the adjacent motorway, which leads to the ferry port. At the time, charities working on the ground estimated that this would mean the displacement of more than 1,000 people. It was suggested that at least some of the displaced could move into these newly built converted shipping containers. Among residents of the ‘Jungle’, the reaction to the new containers – presented generally in the British media as a generous gesture – was decidedly mixed. Although they offered a warm and dry place to sleep for 1,500 people, the fear was that the registration information and biometric data that were gathered as the condition of a place (entry is granted by a handprint scanner) might be used against any refugee reaching Britain and making an eventual asylum claim under the Dublin Regulation. More generally, many also felt that by moving into the new containers they would isolate themselves from family, friends and the broader social environment of the camp. One resident described the containers as being ‘like a prison camp’. © Rob Pinney

Cricket in Afghan Square, January 2016. Although still bitterly cold, this was the first full day of sunshine after several weeks of rain, during what was for many refugees their first experience of a northern European winter. Under these conditions, once clothes become wet, they are almost impossible to dry out again – so many refugees made full use of this momentary shift in the weather to get out and play. The shipping container in the background houses a small fire engine, built and funded by volunteers from the United Kingdom and operated by a small crew of trained refugees. © Rob Pinney

Rob Pinney is a documentary photographer and researcher with a particular interest in war, post-conflict, displacement and migration issues. His project in Calais is ongoing, a portion of which is now available as a book, The Jungle, available at Call Me By My Name. To see the full series, visit his website. His Twitter handle is @robpinney and his Instagram account is @rob.pinney.

2 June, 2016

As a way of setting the scene to our newest exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond, Professor Robert Tombs has written this historical account of the city and its enduring importance on both sides of the Channel.

Burghers and roast beef

The bit of the continent closest to England has always been hugely important to us islanders – so much so that, for more than 200 years, it was actually part of England.

During the long medieval wars between France and England, it was besieged and captured by Edward III in 1347. When the town surrendered, 12 burghers were threatened with hanging by Edward, but spared by his Queen Philippa – a drama immortalised by the sculptor Auguste Rodin in a sculpture now displayed next to the Palace of Westminster.

The Siege of Calais, 1346–47. Artist unknown.

Edward expelled its native population, and made Calais into an English trading post and military and naval base, with thousands of merchants handling England’s greatest export to the Continent – wool. Dick Whittington was its mayor in 1407. It was represented in parliament, and its profits provided up to a third of England’s tax revenue. Its sizeable hinterland included Sangatte, and it was strongly fortified and defended by a large professional garrison.

In the 1450s, it was commanded by the Earl of Warwick, ‘the Kingmaker’, and this enabled him to play a crucial role in the Wars of the Roses. However, Calais’ trade declined, its defences crumbled, and when it was captured by surprise by the French in 1558, it was important only as a blow to the prestige and popularity of the Queen, Mary Tudor, who famously said that ‘Calais’ was written on her heart.

In later centuries, the story was rather one of tourism. Calais was where the English had their first taste of the Continent. William Hogarth’s satirical 1748 painting, O the Roast Beef of Old England (‘The Gate of Calais’), now on display at Tate Britain, showed the contrast as patriotic Brits like himself saw it: between free and prosperous Britain and poor and down-trodden France.

‘O the Roast Beef of Old England (The Gate of Calais)’ by William Hogarth: Tate Britain.

In the 18th century, Calais’ famous Hôtel de l’Angleterre – with its own theatre and carriage hire – was said to be the finest in Europe. Calais was also a place of refuge for those islanders who had blotted their copy book at home. There were so many British residents in the 19th century that it had its own English-language newspaper.

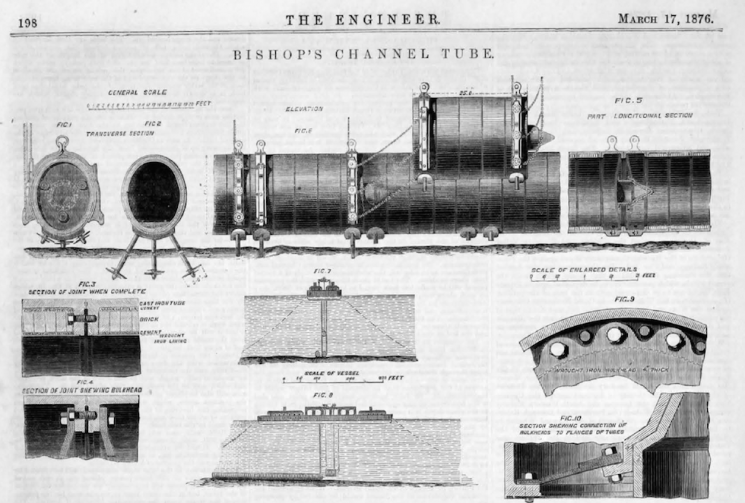

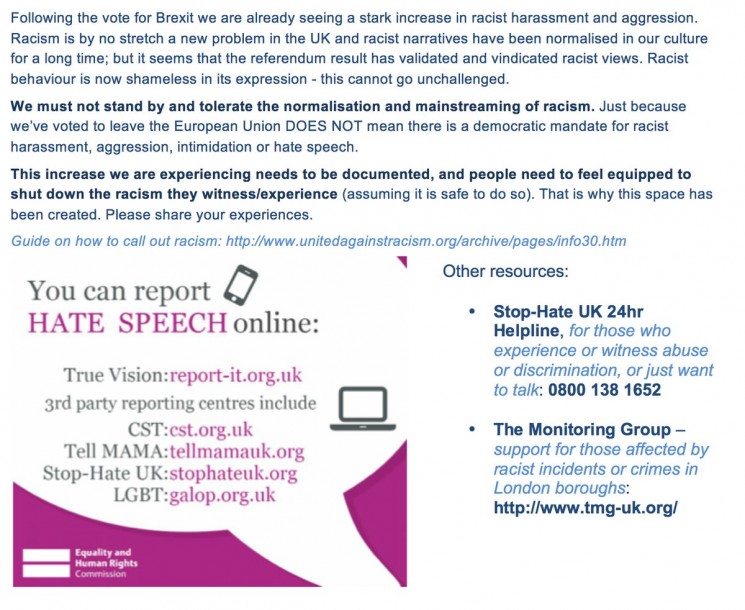

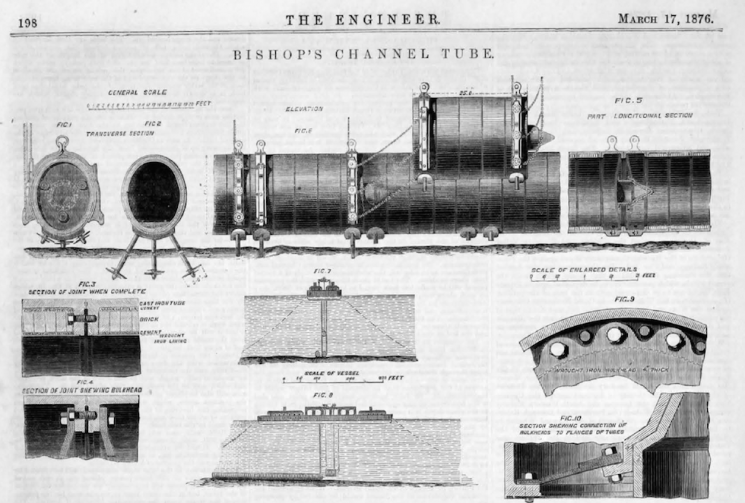

As early as 1802, a plan had been put forward to build a Channel tunnel, and in the early 1880s work actually began at both Sangatte and Dover, and pushed a couple of miles under the sea. But the War Office feared it might be used to launch a surprise invasion, and put a stop to it. After the First World War, the prime minister, David Lloyd George, told the French that he would build a tunnel so that Britain could send aid to the French if they were again attacked, but once more the War Office vetoed it. In 1940, a British garrison defended Calais bravely until overwhelmed by the invading Germans.

Paul J Bishop’s Channel Tunnel Tube, designed in the 1870s, was designed to sit on top of the seabed rather than boring beneath it.

Always one of the main gateways from England to the Continent, its role as a seaport was of course transformed by the building of the Channel Tunnel, which opened in 1994 after more than a century of false starts.

Calais today has become notorious for another reason: for centuries the route by which the British came to Europe, it has now become a symbol of the desperate efforts of refugees and migrants to leave Europe in the hope of economic opportunity in Britain.

Inside a squat in a former factory, Calais. The factory has since been evacuated. © 2015 Christian Sinibaldi

But this is not the first time that Calais has been an escape route. Many French Protestant Huguenots passed through it in the 1680s, and then a century later came thousands of refugees from the French revolutionary Reign of Terror. Successive waves of asylum seekers, including kings and prime ministers, took the same route. In 1848, British workers attacked by xenophobic revolutionary mobs had to take refuge on Channel ferries.

As long as there are people who, for whatever reason, seek shelter in Britain, Calais will be the primary port of call.

Professor Robert Tombs, lecturer in modern European history at St John’s College, Cambridge, and author of The English and their History, will be appearing in our panel discussion on ‘What is Britishness?’ at our Call Me By My Name exhibition (Londonewcastle Project Space, 28 Redchurch Street, Shoreditch, London E2 7DP) on Tuesday 14 June, 7–9pm.