Archives

22 February, 2017

Waiting for the midnight hour

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Indian Independence. On 15 August 1947, ‘At the stroke of the midnight hour,’ as India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, sonorously proclaimed, ‘when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.’ And so it did, but it awoke too to the realisation that its borders had been redrawn, that the state of Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east had been divided in two, and a new country, Pakistan, created to accommodate a predominantly Muslim population.

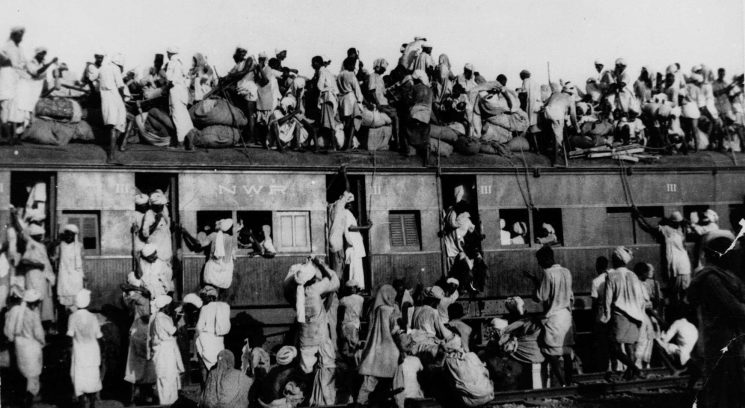

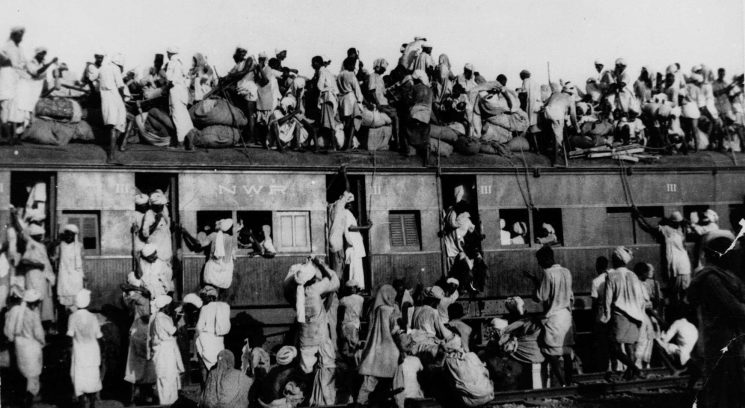

Indian Independence has therefore always been synonymous with the partition of India, with which it coincided almost exactly. The new boundaries of Punjab and Bengal were formally announced only the day before Independence, so that millions of households in those two states woke up to find themselves living in a country that no longer aligned with their religion: Muslims in the southern half of the states having to move north to a new home in Pakistan, Hindus and Sikhs in the northern half having to move south to India. There began what still stands as one of the largest migrations in history, with estimates of between 14 and 16 million people moving across the newly formed borders in the hope of finding sanctuary. Neither the newly created independent governments, nor the British administration in India under its last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, were prepared or equipped to deal with the scale of this migration, or to contain the religious violence that duly ensued, so the independence of both countries was marked by bloodshed. How many people died in the weeks and months following partition is still unclear: the lowest estimate, given out by the British administration (which had previously pledged there would be no violence), is 200,000 deaths; the highest estimate is 2 million.

Easy to see why ‘celebrating’ this anniversary is particularly problematic.

Easy to see, too, why teaching it in schools – whether in this country or in India or Pakistan – has often appeared too challenging to take on. Families were riven in the process of partition, and many continue to maintain a cloak of silence over the events; where there is discussion, there are so many contested narratives that it feels impossible to present it with sufficient historical detachment. For all these reasons, it’s not surprising that so little is known now about this period of Anglo-Indian-Pakistani history.

Muslim refugees clamber on top of a train leaving New Delhi for Pakistan in September 1947.

Drawing the line

There are signs, though, that this might be changing. Last Wednesday, 15 February 2017, the Runnymede Trust’s report into the Partition History Project (PHP) pilot school programme was presented in the House of Lords to a packed council chamber. The pilot had been delivered in the winter term of last year, a time of heightened sensitivity around the issues of migration as a result of the EU referendum and the US presidential elections. It was delivered in four schools in Luton and Hitchin, with markedly different student populations, all of which, however, even those with a significant proportion of students of Bengali or Pakistani heritage, knew very little about the events. The pilot combined history lessons delivered to key stage 2 and 3 students, and the showing of a play, Child of the Divide by Sudha Bhuchar, which told the story of partition through the experience of one child. The headline results of the report are staggering, with a 70 per cent increase in students’ understanding of the events and clear indications that the use of drama, as a way of exploring an historical event through the prism of one family’s experience of it, had been hugely successful.

Perhaps understandably, teachers felt that teaching the story of partition in two lessons was asking a bit much, and the results of the PHP seem to bear this out. Although students retained a considerable amount of information, there was also some confusion about the circumstances leading up to partition, the identity of the key players in the events, the scale of the displacement that resulted and the nature of the religious groups affected. Two clear messages emerged: first, that teaching the history of partition effectively has to be undertaken in the context of British rule in India and in a broader discussion of Empire; and, second, that the subject of partition has particularly rich potential for a discussion of some of the issues of the day, including community cohesion, migration, religious pluralism and the legacy of Empire. Often these issues are confronted more comfortably through the prism of an event at some historical distance from the present.

The panel prepares to debate in Committee Room 2, House of Lords, Wednesday 15 February 2017. The panel, chaired by Rita Chakrabarti, included Professor Sarah Ansari (Royal Holloway, University of London), Lord Meghnad Desai, Lady Kishwar Desai (Partition Museum), Farah Elahi (The Runnymede Trust), the Reverend Canon Edward Probert (Salisbury Cathedral) and Canon Michael Roden. © Runnymede Trust

Lady Desai, who will be delivering the Migration Museum Project’s annual lecture later this year on partition, spoke from the panel with passion and interest about the process of establishing the first Partition Museum, which is due to open in autumn this year in Amristar. What is clear is that, although there are many who would still prefer partition to go undocumented or certainly uncommemorated, there are even more people who recognise this as their story and who are clamouring to be involved in it.

That same sense emerged from the response of the meeting to the panel’s discussion. Time and again people spoke about how their parents or their grandparents were only now beginning to talk about these events, having maintained a silence for the best part of 60 years, making them – the children and grandchildren of partition – viscerally aware of the division that it had caused in their families and extended families. The worry is, people who lived through these events are now in their 80s and 90s themselves: are we going to be able to capture their first-person records before (morbid thought) they leave us?

But there were a significant number of positives about the project, the report and the meeting, too. It was heartening to hear about the creation of an institution unafraid to commemorate such a complicated period of its country’s history. It was good, too, to feel that in this country there was an appetite for confronting historically contested narratives and encouraging some dialogue around them. It was reassuring, from the selfish perspective of the Migration Museum Project itself, to see how successful the use of drama had been in the pilot’s delivery, since we have long maintained that the human stories of migration have a weight and a pull that ‘objective’ accounts get nowhere near. And it was good, too, at a time when it occasionally feels that people are retreating into themselves and putting up the shutters, to feel that so many people were hungry to discuss these difficult matters and to throw open the curtains and let the light in on what had previously been kept under wraps.

The Runnymede Trust is an independent charity ‘working to build a Britain in which all citizens and communities feel valued, enjoy equal opportunities, lead fulfilling lives, and share a common sense of belonging’. The report mentioned in this blog may be downloaded here; anyone interested in finding out more about the report or about Runnymede is welcome to write to Farah Elahi, research and policy analyst at Runnymede.

8 February, 2017

Martin Spafford, who sits on the Migration Museum Project’s education committee, writes here about developments to public examination at GCSE which, for the first time, enshrine migration education on the school curriculum. Emily Miller, the Migration Museum Project’s education manager, is working with Martin to promote migration education in schools.

Migration and the new GCSE curriculum in England

At a meeting about curriculum change in 2012, Nura Hassan, a 16-year-old East London school student, had this to say about school history:

‘If history is a cake, the government is cutting a small slice and forcefeeding it to us, pretending it’s the whole cake.’

Nura was referring to the fact that the rich diversity of the peoples of these islands was all but absent from what is taught in schools. Since then, two of the three English exam boards – OCR and AQA – have attempted to address the issue by making changes to their courses. As a result, 14–16 year olds in state and private schools across England – from rural Gloucestershire to urban West Yorkshire, from Southall to Norfolk, from Milton Keynes to Maldon – are studying the long history of migration to and from Britain for their GCSE exams. (For an account of the three available courses, see the text box at the end of this blog post.)

Government changes in the content of the history exam mean that all students must now study a theme, examining it across an extended period of time from the early Middle Ages to the present; schools select one theme from three offered them by the exam boards, and with three out of the four courses available migration is now one of those options. A head of history in West Yorkshire has said he has never been as excited about teaching as he was starting this topic, which allows his students of diverse heritage to see their place in our history. A Brent teacher said the lesson she designed to open the unit was met with greater enthusiasm by her students than any she had ever taught. A Midlands teacher says that the key concepts in the course – reasons for migrating, experiences, impact of migration, and the extent to which migrants have been accepted or rejected – are so close to his students’ own lived experience that they understand them easily when handling them as historians.

One of Hodder Education’s publications for the new GCSE syllabus; Martin Spafford, this blog’s writer, is a co-author.

A black soldier is shown with a rifle on the left of this relief panel showing Nelson’s death, from the base of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square.

New resources have been published, which some schools are using to rethink and change the way in which they teach younger pupils. In an East London school a new approach to key stage 3 for 11–14 year olds ensures that the many experiences of our diverse population are fully reflected in what is taught about every period in our history. A project run jointly by an Essex secondary school and 14 feeder primary schools resulted in years 5, 6, 7 and 8 of the schools working together to create a migration museum. Islington Council’s ‘All world history, all the year round’ programme, a move forward from Black History Month, is becoming embedded in some primary and secondary schools, spearheaded by the community organisation Every Voice.

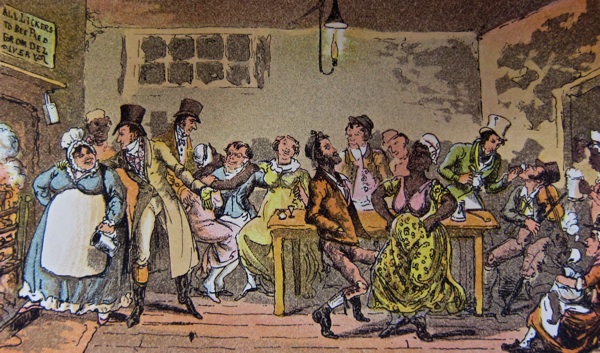

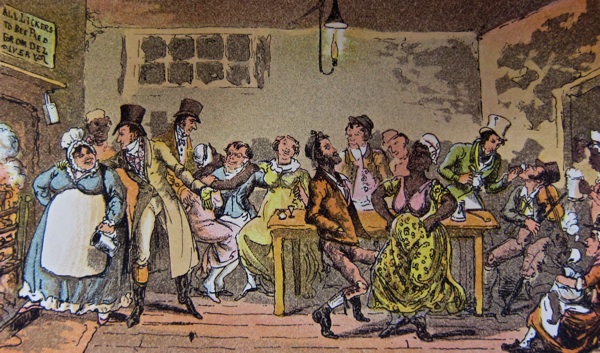

‘The Lowest Life in London’ – a cartoon by George Cruickshank, 1820.

Children studying Roman Britain can therefore learn that most of the ‘Romans’ who came (soldiers and civilians) were from Northern Africa, Western Asia, Eastern and South-Western Europe – and that many settled. Students can discover how the economies of medieval and early modern England were transformed by the skills, influence and investment of Jewish moneylenders, Flemish weavers, German merchants, Lombard bankers and Huguenot entrepreneurs. By looking at the free lives of Africans in Tudor England we can have a fresh understanding of how racial attitudes were later shaped – in devastating ways – by enslavement and empire. The industrial age can be seen through the lives of migrants from Ireland and Italy, as well as those from all parts of Britain, who constructed and worked the factories, roads and railways. Without Asian merchant seamen, not only the trade routes of the British Empire but also the Atlantic convoys in both world wars would have been impossible. And through the memories of parents and grandparents students can see how migration since 1945 has played a huge role in our economic, political and cultural life.

A representation of John Blanke, the trumpeter at the court of King Henry VIII. © Stuart M.

These are early days: schools choosing the Migration options are a minority, and projects with earlier years are just beginning. But we live in a climate of heated and often poorly informed debate, so it is increasingly important to equip children with knowledge that is based on evidence and research. Against that background, the acceptance of migration as a valid subject for school examination, and the availability of new resources that tell so many stories previously untold in schools, cannot have been more timely – even if both come, unfortunately, too late for Nura.

The courses on offer for teaching migration at GCSE

Migration to Britain – part of OCR’s ‘A’ Explaining the Modern World course. Students investigate the extent to which immigration has shaped this country – economically, politically and culturally – from before the Norman Conquest until now, giving a historical context within which to try and unpick the contemporary debate. Students also look in depth at the period from 1688 to 1730 and how the development of capitalism and a growing empire – in Ireland, Scotland, India, West Africa, North America and the Caribbean – created so many aspects of modern Britain. The course also includes a close look at historical patterns of migration in a different urban area each year: the current one is Butetown in Cardiff, while future years will study South Shields, London’s Spitalfields, Liverpool’s Toxteth and St Pauls in Bristol.

Migrants to Britain – part of OCR’s ‘B’ Schools History Project course. Covering much of the same ground as the ‘A’ course, it focuses strongly on the lives of ‘ordinary’ people and what their stories tell us about the past. Starting with the build-up to the expulsion of the Jews in 1290 and finishing with the 2016 ‘Brexit’ referendum, the course asks a series of questions about each of four periods: medieval, early modern, industrial and modern. What part did migrants play in the life of this country? How accepted were they? What were their experiences? How has Britain responded to migration? What has been their impact? In the text book there are also ‘closer looks’ at the stories told by the database of a medieval research project, a lonely Lancashire tomb, changes in one street over time, an internee’s experience and the painting and poetry of the children of 20th-century immigrants.

Migration, Empires and the People – part of the Shaping the Nation strand of the AQA history course. It looks at immigration and emigration in the context of the growth of Britain’s global presence and, in particular, its empire. It moves across the world in focus, starting with England’s relationship with medieval Europe, then the Atlantic world in the 16th to 19th centuries, then British expansion in India and Africa, and finally the legacy of empire in the 20th and 21st centuries. Students look at key historical figures, including immigrants and emigrants ranging from Emma of Normandy and Mary Fisher to David Gestetner and Claudia Jones.

All the above courses have high quality, richly illustrated textbooks published by Hodder Education. Taken together, the three books provide a rich and wide-ranging look at our migration history and relationship with the wider world:

• Migration to Britain by Adi, Lyndon, Sherwood and Spafford

• Migrants to Britain by Lyndon and Spafford

• Migration, Empires and the People by Mohamud and Whitburn

A comprehensive resource and learning pack on Butetown, Cardiff can also be accessed and freely downloaded as a PDF. And the accompanying Our Migration Story website created by the Runnymede Trust is also free to access is.

Martin Spafford co-wrote the Hodder textbooks for the OCR migration courses and is a member of MMP’s education committee. Now retired, after nearly 40 years’ teaching (latterly in East London), he is now a volunteer trainer with www.journeytojustice.org.uk and a facilitator on a leadership project in West London schools run by Facing History and Ourselves. He enjoys working with young people around the meeting places of education, history, social justice, human rights and community action for change. At the moment he is preparing a schools pack on the migration history of South Tyneside.

15 November, 2016

Gurkhas occupy an interesting place in British folklore. Universally recognised as ferociously loyal, heroic and determined fighters in the British army, they were only recently given right to settle in this country, and then only after a high-profile media campaign. In this guest blog, Krishna P Adhikari recounts what is known of one of the first Nepali visitors to Britain, Motilal Singh, who came to the country halfway through the 19th century.

Motilal Singh: soldier, crossing sweeper, chronicler

This year marks the bicentenary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Nepal and Britain. Although the recruitment of the Nepalis (as Gurkhas) into the British Army started 200 years ago, restrictions on Gurkha migration to Britain were eased only a decade ago, in part the result of a memorable public intervention by Joanna Lumley. Nepalis are now a fast-growing minority group, estimated at around 100,000 people and spread across the UK, with a tendency to cluster around towns with strong links to the British Army, such as Aldershot and Folkestone. Many non-Gurkha Nepalis in the UK work as doctors, nurses, academics and entrepreneurs. Overall, Nepalis form a culturally diverse and economically active group.

The first Nepali to set foot in Britain was long thought to have been Nepal’s prime minster Jang Bahadur Rana, who visited Britain and France in 1850, along with 24 other Nepalis, and who met Queen Victoria on three occasions. He was recognised as an ambassador, and an article in The Economist on 1 June 1850 wrote, ‘He is the first Hindoo of so high a caste who has ever been presented to the Queen.’

This turns out not to be the case, however. When I was studying and writing a book about Nepali migration in the UK (Nepalis in the United Kingdom: An Overview), I came across a substantial 18-page article called ‘Some Accounts of Nepaulese in London’ in the July 1850 edition of the New Monthly Magazine and Humorist. This article, written by a man called Motilal Singh (whose name was anglicised as Mutty Loll Sing), reveals that he reached Britain several years before Jang Bahadur arrived in London. Motilal Singh had previously been unknown to Nepali historians, and his article unveils important information about himself, his encounter with Jang Bahadur and life in the UK.

Junga Bahadur Rana (1817–77), the first Nepali prime minister to visit Great Britain – but not the first Nepali to do so.

Motilal Singh was born in Bhaktapur in the Kathmandu valley, and was 19 when he fought in the Anglo-Nepali war. He was wounded, captured and imprisoned. Appreciating the bravery and valour of their opponents, the East India Company formed the first battalion of Gurkhas in 1815, which Motilal joined. There he learnt to speak English. Later, he married in Calcutta (Kolkata) and had several children.

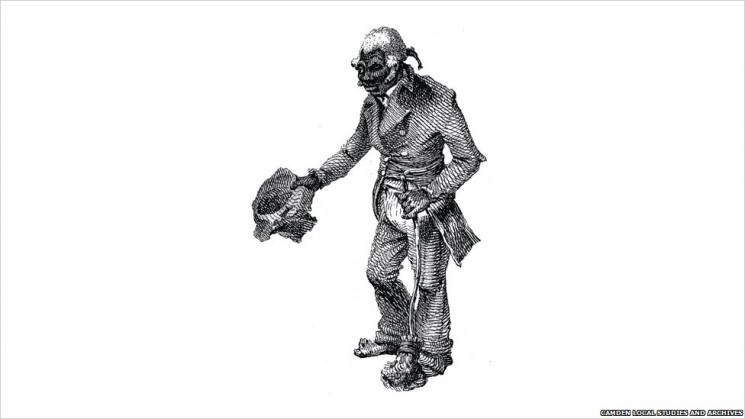

Motilal would have lived happily with his family if it were not for an English captain who persuaded him to move to Britain. Those days the East India Company needed ‘Lascars’ (the term given to sailors from India and south-east Asia) to sail the ship or to work as militiamen, and they thus formed the first group of migrants from Asia in Britain. Motilal was given the false impression that he would be able to collect huge amounts of gold and return home. Instead, he lost his money and was left ‘neglected and despised in a strange land … in the cold streets of London, hungry often, often athirst … ’

In a surprising turn of events, Motilal came across the members of the Nepali mission on 27 May 1850 and soon after was rescued from London’s St Paul’s Churchyard, where he had been living for years as a crossing sweeper. In Victorian times, the beggars in the street of London included those from poor families, children and also ‘Hindus, Lascars, or Orientals of some sort’.

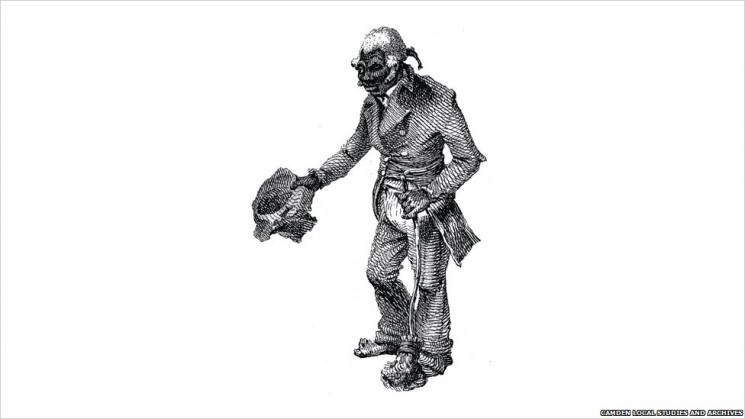

Charles McGee, a crossing sweeper in Ludgate Hill and one of the ‘St Giles Blackbirds’, London’s first black community. ‘Blackbirds’ was a term used during the 18th century to describe black beggars who were often freed slaves. Charles McGee was working 30 years before Motilal Singh. © Camden Local Studies & Archives

Several newspapers sensationalised the story: ‘Everyone who has passed through St Paul’s Churchyard to Cheapside on a rainy day, when birch brooms are very much in requisition, must have noticed the well-known Hindoo crossing sweeper … He now appears in the carriage of his Excellency every morning arrayed in a new and superb Hindoo costume … ’ Motilal was taken to Richmond Terrace in Westminster, where the Nepali Embassy was housed. He was a valuable member of the mission and visited many places as an informal interpreter. It is safe to say that meeting Jang Bahadur in London changed Motilal’s life altogether.

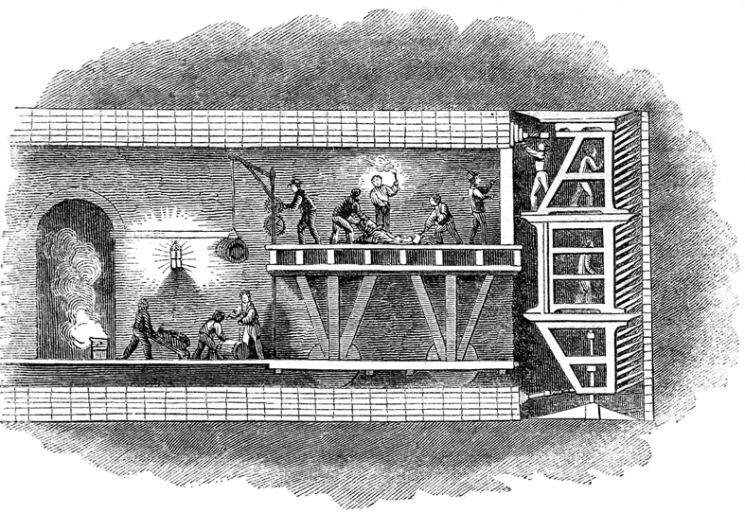

Motilal mentions several events which give some idea about Victorian London. The London underground system, which came into operation much later, was already being built. The party crossed the Thames using a tunnel constructed by a ‘clever Frenchman’ (Marc Brunel, father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel). Motilal describes a steam train, in which the Nepali mission travelled from Southampton to London, as a ‘fire-driven monster’.

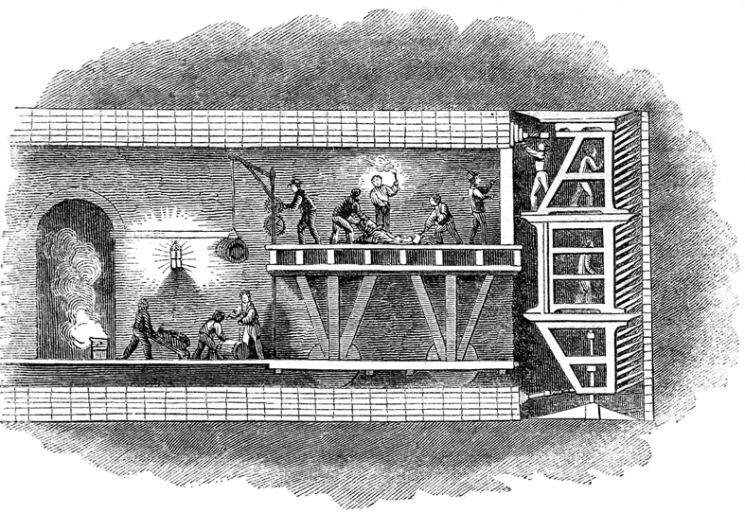

The tunnelling shield, invented by Marc Brunel, father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The shield was used to construct the first tunnel under the Thames at Rotherhithe, which is the tunnel that Motilal Singh visited as part of the Nepali mission. Marc Brunel, the ‘clever Frenchman’, was a refugee from France.

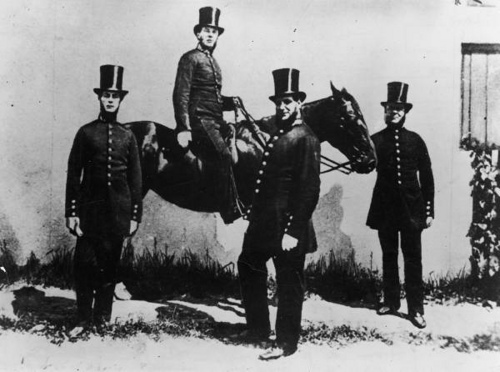

They visited Epsom in a horse carriage to see the horse racing, which they were told was the ‘chief pleasure’ for English people – the Derby being ‘the greatest of all’ in England.

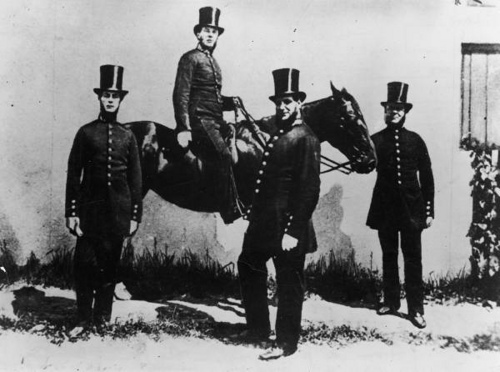

Epsom racecourse in Surrey during Derby week. ‘A’ Division, Metropolitan Police, 1864.

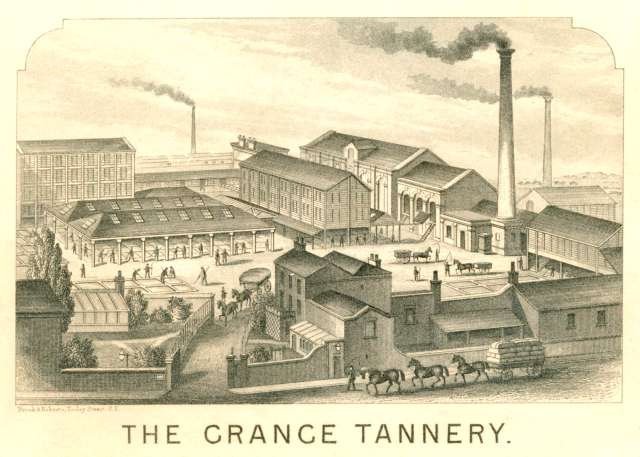

They also visited the world’s largest brewery of the time, operated by Barclay Perkins in Southwark. Nearby was the Phoenix Gas Works, where the city’s light was generated. Motilal describes passing through a ‘thickly populated town’ (which, because of the tanneries, was very smelly) and reports the water of the ‘pious’ Thames as being dirty and polluted.

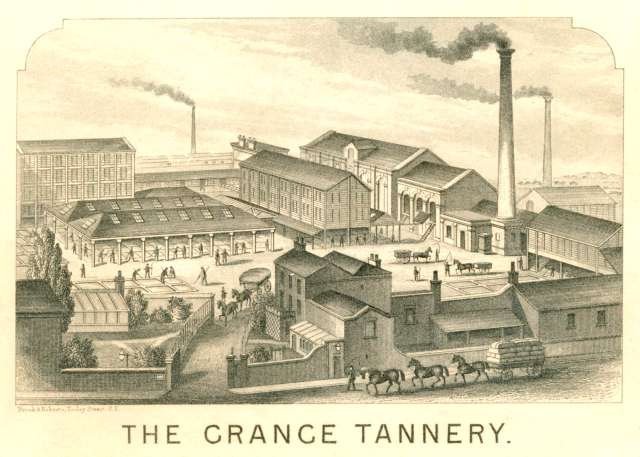

The Grange Tannery, Bermondsey, 1876. Tanning and food processing were the two main industrial activities in the area, both giving rise to some highly unpleasant smells.

The Nepali team visited the St James Theatre (according to Motilal’s account, the British liked the plays but relied on French actors because they were ‘unable to act them’) and attended several grand parties, including one hosted by Benjamin Lumley (no relation to Joanna Lumley, who campaigned on behalf of the Gurkhas), who managed the theatre. Strict cultural differences meant that the Nepalis did not eat or drink anything in these gatherings, which their English hosts (including the Queen) must have found difficult to comprehend. The reason for this was that the Nepalis were teetotal, and their faith in ritual purity meant they refused meals cooked by people they deemed ‘polluted’.

Racial epithets were common in Victorian society, and went both ways: the Nepalis were referred to as ‘the blacks’, and Motilal himself uses phrases such as ‘white as cauliflower’ and ‘red-faced’ to describe the English.

Motilal accompanied Jang Bahadur’s party to Paris, and it is likely that his desire to return home was ultimately fulfilled.

Although an ordinary man, Motilal is an important historical figure because of his travel from Nepal to India and then to Britain and later France, and also because he was the first Nepali known to have visited the UK, and to have published in English.

Perhaps surprisingly to our current-day sensitivities, Motilal’s difficult circumstances in Victorian Britain were in no way helped by his being a Gurkha. Today the context is very different – Gurkhas are held in high esteem – and yet the lives of ex-Gurkhas in Britain are not without problems. Former Gurkhas continue to fight for equal pensions, family visas and other welfare entitlements, and continue to face occasional racial prejudice. A greater appreciation of the long history of Gurkhas living in the UK, going as far back to, and perhaps beyond, Motilal Singh, could help to address some of these issues.

Dr Krishna P Adhikari is a research fellow at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Oxford, and was previously executive director of the Centre for Nepal Studies UK (CNSUK). Among his publications are Nepalis in the United Kingdom: An Overview (2012) and The Mysterious Life of Motilal Singh: The First Nepali in Britain and His Historic Article (2013, in Nepali, with a 2nd edition due to be published in both Nepali and English). He is also a co-author of CNSUK’s British Gurkha Pension Policies and Ex-Gurkha Campaigns (2013). He did his PhD at the University of Reading (2007).

3 November, 2016

‘The sympathy and freedom and liberty of England’

With wonderful timing, the Wiener Library opened its new exhibition, ‘A Bitter Road’, on the reception of Jewish refugees in the 1930s and 1940s, on Thursday 27 October, the day that the Calais ‘Jungle’ was dismantled and its residents dispersed. The coincidence didn’t escape the speakers at the exhibition’s launch, two of whom drew comparisons between the numbers of Jewish refugees taken in by the British government in the war years and the numbers of refugees who have been granted asylum since the Syrian conflict began. As Dan Stone (one of the speakers) said, ‘The number of children admitted through the Kindertransport scheme – although not their parents – was quite large: the same as the number of people in the Jungle.’ (The full transcript of his speech may be read here, on the University of East Anglia’s website.)

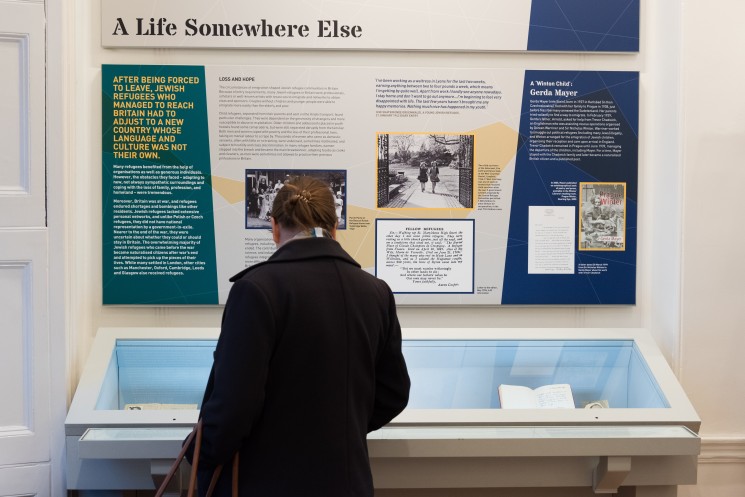

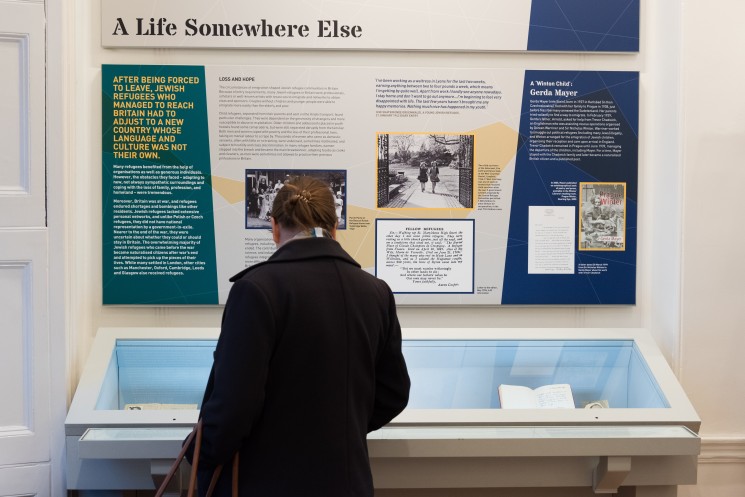

The third section of the exhibition, presenting the individual testimony of refugees. © Morag Macdonald

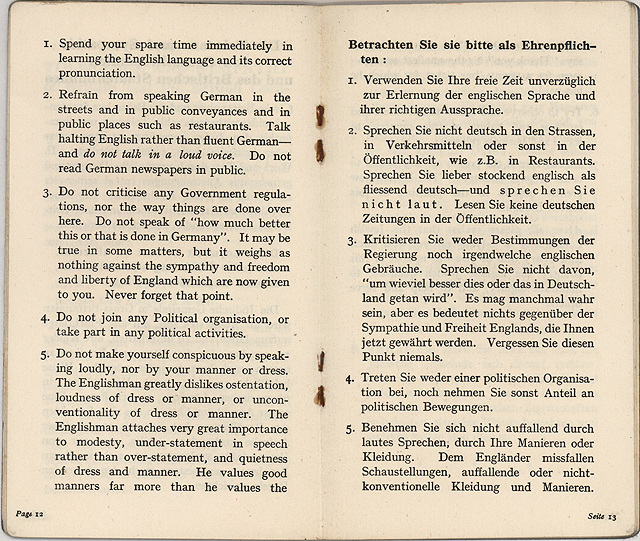

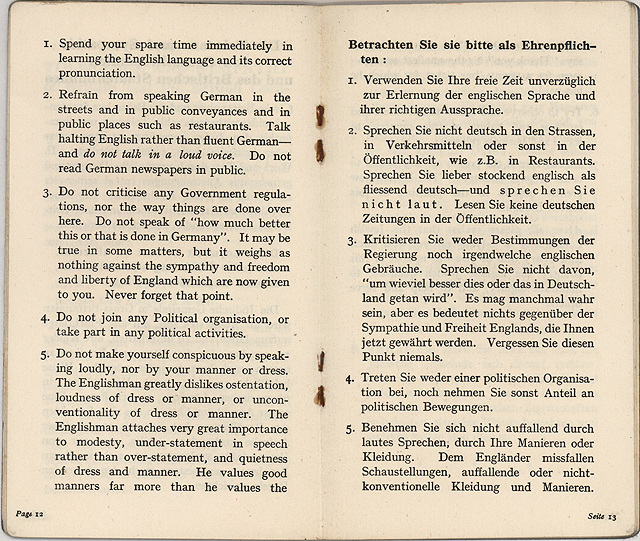

Much of the fascination of the exhibition, sub-titled ‘Britain and the Refugee Crisis of the 1930s and 1940s’, lies in the documentary evidence of ordinary people’s reactions to the experience of emigration and arrival in a new country. Booklets of advice on how to avoid drawing attention to yourself (‘Refrain from speaking German in the streets … the Englishman greatly dislikes ostentation’) make interesting reading, and raise the question of what those booklets would advise now; the complicated process of vetting and vouching for the refugees reveals a national paranoia that feels very contemporary. The suspicion Jewish refugees came under – being predominantly from Germany and therefore seen as potential enemy agents infiltrating Britain – inevitably brings to mind the suspicion currently directed at Syrian refugees and the fear that a refugee may be a terrorist in disguise.

Advice to refugees from Germany on how to behave in England . . . how much has changed? © Wiener Library

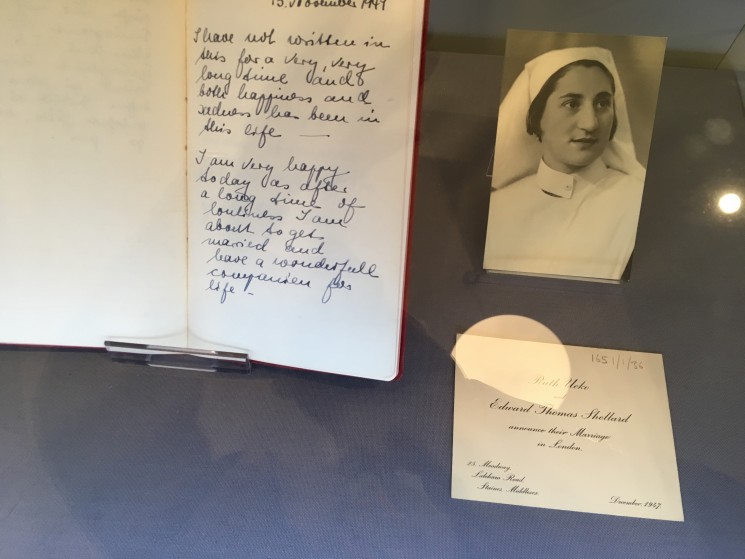

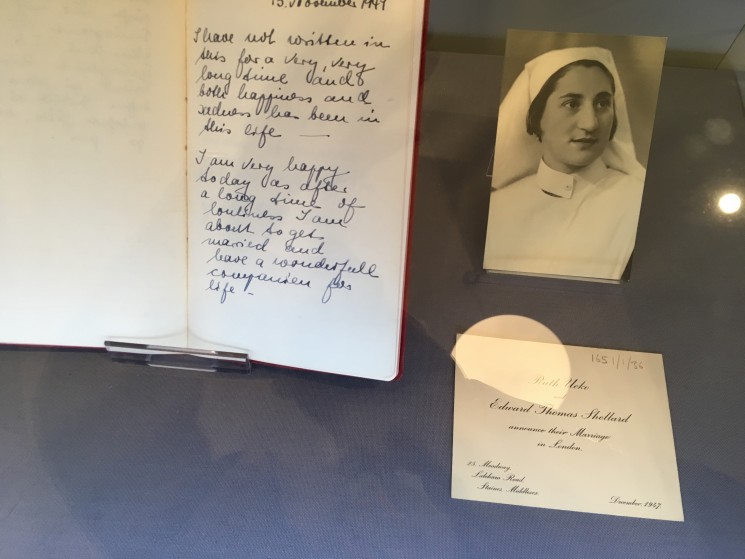

The bureaucratic formality of the reception process, which from this distance looks more obstructive than well-intentioned, contrasts with the more personal correspondence and diary entries presented elsewhere in the exhibition, one of which, written by Ruth Ucko, the first diary entry she wrote in English, announces her impending wedding as an emergence from a period of turmoil. A further section of the exhibition examines the media’s response to the refugee crisis, jumbling together headlines from the 30s/40s with today’s headlines in a way that shows how little has changed over the last 70 years.

A diary entry from Ruth Ucko, her first written in English.

At Thursday’s launch, Ben Barkow, director of the Wiener Library, introduced the three speakers, two of whom – Rabbi Harry Jacobi and Lord Alf Dubs – arrived in this country as refugees, from Holland in 1940 and from Czechoslovakia in 1938 respectively. Rabbi Jacobi spoke movingly about the circumstances of his escape on the last evening before the Dutch surrender to the Germans, a 14-year-old boy in a boat under fire from German bombers. He paid tribute to the woman who saved him, Gertuide Wijsmuller-Meijer, in a similar way to Alf Dubs’s recognition of the intervention of Sir Nicholas Winton (one of whose letters is part of the exhibition). Alf Dubs – the author of the Dubs’ Amendment, whereby unaccompanied refugees are to be offered safe refuge in this country – drew parallels with the current refugee crisis (the jury is still out, he claimed, on how his Amendment was being implemented), parallels that are a firm part of the exhibition, too, and on which Dan Stone, professor of modern history at Royal Holloway, University of London, focused in his talk:

Of the world’s 65 million refugees, some 10,000 tenaciously made their way to Calais, where they were stopped from proceeding to the UK and where, until a few days ago, they set up camp in the Jungle, a place which should never have been allowed to exist in one of the richest corners of the world (I’m talking of Europe as a whole, not Pas-de-Calais). Ten thousand is a six-hundred and fiftieth of 65 million, or 0.015%. These are not people who lack initiative or talent; they have determinedly made their way across dangerous terrain and ugly encounters with people smugglers and border guards in order to fulfil their dream of entering Britain. This country, with its ‘proud tradition of helping the oppressed’, has denied them entry and, with the exception of a few hundred children hurriedly allowed in as the French were sending in the bulldozers, refused even to allow children with relatives in the UK and, under Lord Dubs’s amendment, unaccompanied children, to enter, leaving them exposed to the dangers of the camp. Words such as ‘cynical’ come to mind.*

The exhibition is open until 17 February 2017. If you find yourself with half an hour to spare in the Russell Square area, I urge you to visit it. In fact, go and visit it anyway!

‘A Bitter Road: Britain and the Refugee Crisis of the 1930s and 1940s’ is open to the public between 10am and 5pm, Monday and Friday (10am–7.30pm on Tuesday), at the Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust & Genocide, 29 Russell Square, London, W WC1B 5DP. It runs until 17 February 2017.

*For more of Dan Stone’s speech, visit the University of East Anglia’s website.