28 April, 2017

One of the clear highlights of our ‘Imprints’ walk last October (to judge from the feedback of walkers) was Bill Bingham’s rendition of the ‘Strangers’ speech from Sir Thomas More. Bill, a tireless friend of the Migration Museum Project and the mastermind behind the video tent in our current exhibition of Call Me By My Name in the Migration Museum at The Workshop, will be performing the same speech this coming Monday. His account below gives the background to the speech and the details of Monday’s activities.

The Stranger’s Case

There is a very special – and topical – 500th anniversary coming up this Bank Holiday Monday (1 May).

Evil May Day riot in Cheapside, 1517.

St Martin’s le Grand near St Paul’s Cathedral was the scene of a huge anti-immigration riot in 1517 aimed at the Dutch, Flemish and other foreigners, or ‘strangers’ as they were called. The then Under-Sheriff of London, Thomas More, was called on to try and quell the mob. The event is referred to in history as ‘Ill May Day’, or ‘Evil May Day’.

A speech by William Shakespeare from the late-16th/early-17th Century play Sir Thomas More, written in Shakespeare’s own hand, is held at the British Library, along with other sections of the play.

A page from the surviving playscript of ‘Sir Thomas More’, showing Shakespeare’s ‘Strangers’ speech. The script is held at the British Library. © The British Library.

Three actors, Tim Bentinck (who plays David Archer in the BBC’s The Archers), Bill Bingham and Lachlan McCall are marking the anniversary with a 10–15 minute extract from Sir Thomas More, including the Shakespeare/More call for the rioters to disperse,in four venues around London:

- 10.30 – the new headquarters of the Migration Museum at The Workshop in Lambeth

- 13.00 – Postman’s Park close to St Martin’s le Grand

- 17.00 – Bankside, the steps outside Shakespeare’s Globe

- 19.45 – Montague Close, behind Southwark Cathedral

If there are any more details, they will be added to this blog over the weekend.

Young apprentices attacking ‘strangers’ in the days leading up to the Evil May Day riots of 1517. © British Museum.

31 March, 2017

After Khalid Masood’s attack on Westminster last week, both Birmingham and Islam were singled out for critical comment in some of the nation’s press – Birmingham being once again branded the UK’s prime jihadist recruitment centre, and Islam criticised for its callousness, as evidenced by the photograph of a young Muslim woman walking past one of the victims with apparent disregard. Jamie Lorriman, who took the photo, felt he had to defend the young woman against those who had used his photo to further an anti-Islam agenda, clarifying the context and drawing attention to her obvious distress. And Tariq Jahan, hero of the hour in the 2011 riots in Birmingham, gave an equally stout defence of his home city, drawing particular attention to its cultural cohesion, the very quality some of the press had claimed it lacked.

Against this background, Liz Hingley’s blog feels particularly timely. Born in Birmingham, she documents her birth city’s multi-faith communities with understanding and affection, projecting the power of religion to build bridges rather than to burn them. For more information of Liz’s work, see the links at the end of her piece.

The flyover leading from Birmingham city centre to the two-mile stretch of Soho Road. The area has one of the highest immigration and also poverty rates in the city. © Liz Hingley

Under Gods

Growing up in Birmingham, one of the UK’s most culturally diverse cities and home to citizens of more than 90 different nationalities, I was the only white British girl in my nursery class. I ate sweet Indian treats at friends’ birthday parties and attended Sikh festivals in the local park. After travelling abroad and living in other cities, I became aware of the particularity of my upbringing. I developed an interest in the growth of multi-faith communities in European inner cities, and the attendant issues of immigration, secularism and religious revival.

Between 2007 and 2009, I explored the two-mile stretch of Soho Road in Birmingham – the site of some 30 religious centres – documenting and celebrating the rich diversity of religions that co-exist there, and the reality and intensity of their different lifestyles. I lived with and visited the different religious communities, including Thai, Sri Lankan and Vietnamese Buddhists, Rastafarians, the Jesus Army evangelical Christians, Sikhs, Catholic nuns and Hare Krishnas. The lively bus journeys along Soho Road on a Sunday were always insightful. They took Christian individuals to church congregations meeting in a tent in the local park or a school gym hall. Converted Iranian evangelical Jesus Army members in multi-coloured camouflage print outfits could be found sitting next to large decorative hats adorning Jamaican born ladies. On the same bus I would hear Muslim girls sitting at the back talking loudly about the latest fashions of the veil, while I chatted to Hare Krishna devotees on their way to central Birmingham to distribute books.

Under Gods: Stories from the Soho Road is a result of my own journey along Soho Road. What I was aiming to do with this intimate documentation was to show the significance and influence of religious identity in the city and how belief transforms urban spaces from the ordinary to the extraordinary. Under Gods investigates the power of what the people on the street believe their religion to be rather than what is prescribed by religious leaders or by the texts, as faiths are interpreted differently within each context of encounter between persons, places and objects. As a South Asian female Anglican priest said:

On Soho Road people are conscious of their faith rather than where they came from. People used to say ‘Oh I am from Bangladesh, Pakistan, West Indies or Poland.’ Now people say ‘I am a Muslim, I am a Sikh, I am a Baptist, I am a Catholic; this is my identity.’

At a time when religion can breed unnecessary fear and prejudice through misunderstanding, I hope that Under Gods reveals and celebrates the power of faith to form identity and to unify communities in contemporary inner-city life.

Hare Krishna book distribution outside a parish church – a Brazilian-born Hare Krishna devotee hands out flyers on a December morning and invites people for dinner at the Soho Road temple. At the age of twenty he left his native Brazil to preach about Krishna throughout Europe. © Liz Hingley

The Premier League – Muslim children in the backyard of their terraced house. Their formal Islamic dress is only worn for their daily after-school mosque class. The eldest boy checks the football results in the local paper; his sister speaks with their neighbour, a Jehovah’s Witness, over the fence. © Liz Hingley

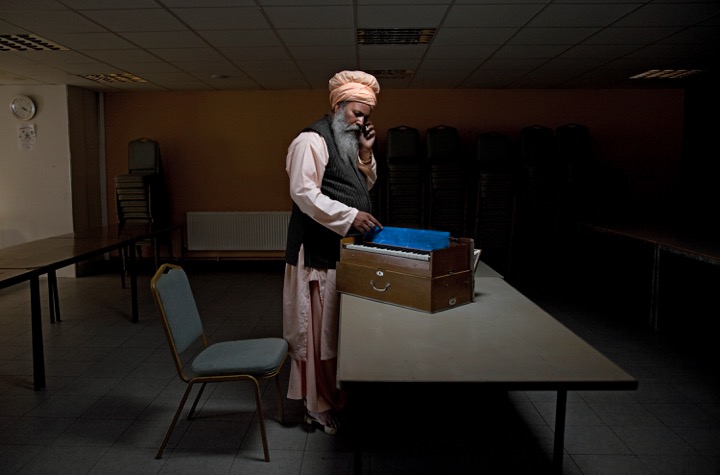

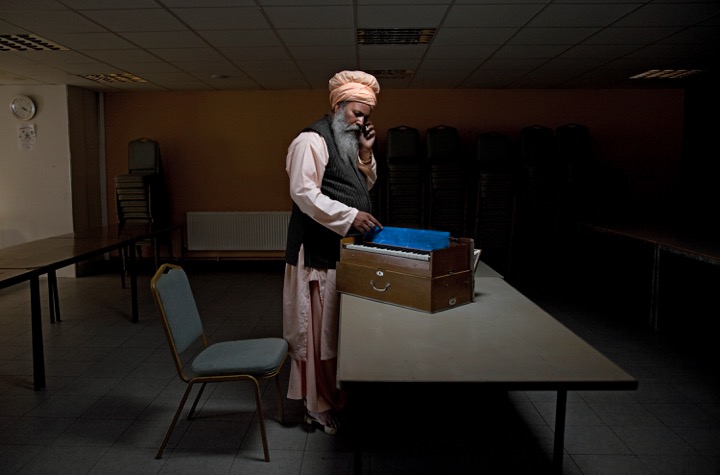

The visitor from India – a Sikh priest visits a Gurdwara on Soho Road. He regularly receives calls on his mobile phone from contacts in India. He speaks no English. © Liz Hingley

The biannual baptisms are an important occasion for the primarily black congregation at Cannon Street Baptists. During the service the baptism pool is uncovered and the pastor, supporter and person to be baptised enter into the water. © Liz Hingley

Minba Chair, Pakistani mosque – a terraced house converted into a Pakistani mosque. The Minba chair, a replica of that used by Muhammad, was made by the Sikh carpenters down the road. © Liz Hingley

A wedding party eats in Nanak Nishkam Gurdwara, the largest and wealthiest of five Gurdwaras on Soho Road. The temple bustles twenty-four hours a day with visitors praying and women making food in the vast kitchens, which distribute hundreds of free langarunga meals. © Liz Hingley

Old age and poor health means Mrs Little is no longer able to attend the church of St Andrews on Soho Road. The Anglican priest celebrates communion in her front room every week with friends from the church. © Liz Hingley

Liz Hingley is a British photographer and anthropologist whose work bridges academic scholarship and artistic practice. She is currently an Honorary Research Fellow of the Department of Theology and Religion at the University of Birmingham. Under Gods, the project on which this blog is based, may be viewed on her site.

18 October, 2017

The Moss family on the porch of their house in Kingston, Jamaica: Dirrell and Vera Moss with Carmen (9), Erroll (7) Lorna (5), Elaine (2) and Annette (3). The family was planning to emigrate to England, where Mr Moss, a printer by trade, would have heard about job opportunities, and where they hoped to begin a new life. The American government had limited the numbers of Caribbean migrants allowed into the United States in 1952, thereby increasing the amount of immigration to Britain.

22 February, 2017

Waiting for the midnight hour

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Indian Independence. On 15 August 1947, ‘At the stroke of the midnight hour,’ as India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, sonorously proclaimed, ‘when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.’ And so it did, but it awoke too to the realisation that its borders had been redrawn, that the state of Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east had been divided in two, and a new country, Pakistan, created to accommodate a predominantly Muslim population.

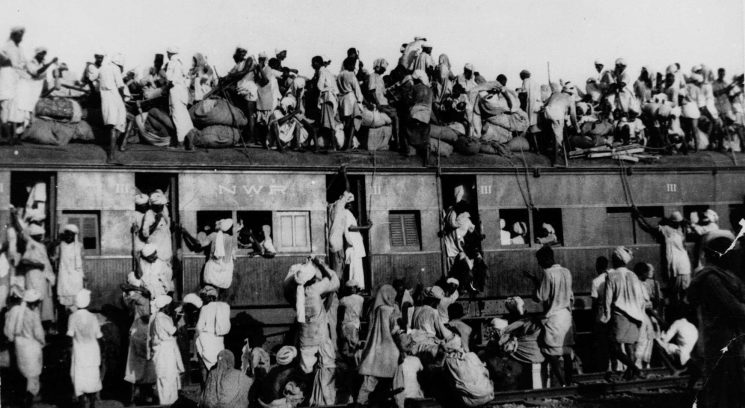

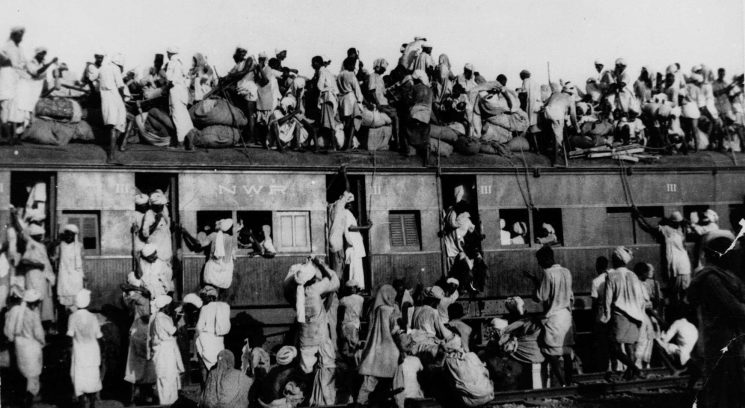

Indian Independence has therefore always been synonymous with the partition of India, with which it coincided almost exactly. The new boundaries of Punjab and Bengal were formally announced only the day before Independence, so that millions of households in those two states woke up to find themselves living in a country that no longer aligned with their religion: Muslims in the southern half of the states having to move north to a new home in Pakistan, Hindus and Sikhs in the northern half having to move south to India. There began what still stands as one of the largest migrations in history, with estimates of between 14 and 16 million people moving across the newly formed borders in the hope of finding sanctuary. Neither the newly created independent governments, nor the British administration in India under its last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, were prepared or equipped to deal with the scale of this migration, or to contain the religious violence that duly ensued, so the independence of both countries was marked by bloodshed. How many people died in the weeks and months following partition is still unclear: the lowest estimate, given out by the British administration (which had previously pledged there would be no violence), is 200,000 deaths; the highest estimate is 2 million.

Easy to see why ‘celebrating’ this anniversary is particularly problematic.

Easy to see, too, why teaching it in schools – whether in this country or in India or Pakistan – has often appeared too challenging to take on. Families were riven in the process of partition, and many continue to maintain a cloak of silence over the events; where there is discussion, there are so many contested narratives that it feels impossible to present it with sufficient historical detachment. For all these reasons, it’s not surprising that so little is known now about this period of Anglo-Indian-Pakistani history.

Muslim refugees clamber on top of a train leaving New Delhi for Pakistan in September 1947.

Drawing the line

There are signs, though, that this might be changing. Last Wednesday, 15 February 2017, the Runnymede Trust’s report into the Partition History Project (PHP) pilot school programme was presented in the House of Lords to a packed council chamber. The pilot had been delivered in the winter term of last year, a time of heightened sensitivity around the issues of migration as a result of the EU referendum and the US presidential elections. It was delivered in four schools in Luton and Hitchin, with markedly different student populations, all of which, however, even those with a significant proportion of students of Bengali or Pakistani heritage, knew very little about the events. The pilot combined history lessons delivered to key stage 2 and 3 students, and the showing of a play, Child of the Divide by Sudha Bhuchar, which told the story of partition through the experience of one child. The headline results of the report are staggering, with a 70 per cent increase in students’ understanding of the events and clear indications that the use of drama, as a way of exploring an historical event through the prism of one family’s experience of it, had been hugely successful.

Perhaps understandably, teachers felt that teaching the story of partition in two lessons was asking a bit much, and the results of the PHP seem to bear this out. Although students retained a considerable amount of information, there was also some confusion about the circumstances leading up to partition, the identity of the key players in the events, the scale of the displacement that resulted and the nature of the religious groups affected. Two clear messages emerged: first, that teaching the history of partition effectively has to be undertaken in the context of British rule in India and in a broader discussion of Empire; and, second, that the subject of partition has particularly rich potential for a discussion of some of the issues of the day, including community cohesion, migration, religious pluralism and the legacy of Empire. Often these issues are confronted more comfortably through the prism of an event at some historical distance from the present.

The panel prepares to debate in Committee Room 2, House of Lords, Wednesday 15 February 2017. The panel, chaired by Rita Chakrabarti, included Professor Sarah Ansari (Royal Holloway, University of London), Lord Meghnad Desai, Lady Kishwar Desai (Partition Museum), Farah Elahi (The Runnymede Trust), the Reverend Canon Edward Probert (Salisbury Cathedral) and Canon Michael Roden. © Runnymede Trust

Lady Desai, who will be delivering the Migration Museum Project’s annual lecture later this year on partition, spoke from the panel with passion and interest about the process of establishing the first Partition Museum, which is due to open in autumn this year in Amristar. What is clear is that, although there are many who would still prefer partition to go undocumented or certainly uncommemorated, there are even more people who recognise this as their story and who are clamouring to be involved in it.

That same sense emerged from the response of the meeting to the panel’s discussion. Time and again people spoke about how their parents or their grandparents were only now beginning to talk about these events, having maintained a silence for the best part of 60 years, making them – the children and grandchildren of partition – viscerally aware of the division that it had caused in their families and extended families. The worry is, people who lived through these events are now in their 80s and 90s themselves: are we going to be able to capture their first-person records before (morbid thought) they leave us?

But there were a significant number of positives about the project, the report and the meeting, too. It was heartening to hear about the creation of an institution unafraid to commemorate such a complicated period of its country’s history. It was good, too, to feel that in this country there was an appetite for confronting historically contested narratives and encouraging some dialogue around them. It was reassuring, from the selfish perspective of the Migration Museum Project itself, to see how successful the use of drama had been in the pilot’s delivery, since we have long maintained that the human stories of migration have a weight and a pull that ‘objective’ accounts get nowhere near. And it was good, too, at a time when it occasionally feels that people are retreating into themselves and putting up the shutters, to feel that so many people were hungry to discuss these difficult matters and to throw open the curtains and let the light in on what had previously been kept under wraps.

The Runnymede Trust is an independent charity ‘working to build a Britain in which all citizens and communities feel valued, enjoy equal opportunities, lead fulfilling lives, and share a common sense of belonging’. The report mentioned in this blog may be downloaded here; anyone interested in finding out more about the report or about Runnymede is welcome to write to Farah Elahi, research and policy analyst at Runnymede.