22 January, 2018

If you find yourself anywhere near Croydon between now and April 2018, go and visit the Gujarati Yatra exhibition, which is nestled away in the Museum of Croydon and occupies the stairwell, corridor and café of the Clocktower building in which it is housed.1

This exhibition tells the story of the double diaspora of the Gujarati people, many of whom left the westernmost state of India in the 19th century to develop the trade and the industry of ports in the east and south of Africa, before being forced in the 1970s to leave their African homes and communities to find refuge in the UK and other countries. Anyone only partially familiar with the story of this population will find plenty of treasures in the exhibition, which is dominated by the oral and video testimonies of Gujaratis living in Croydon (host to one of the largest Gujarati communities in the country) and other parts of London and the UK, and by objects and artefacts loaned by ordinary people and by academics and historians. These oral histories and personal testimonies clearly shaped the narrative of the exhibition.

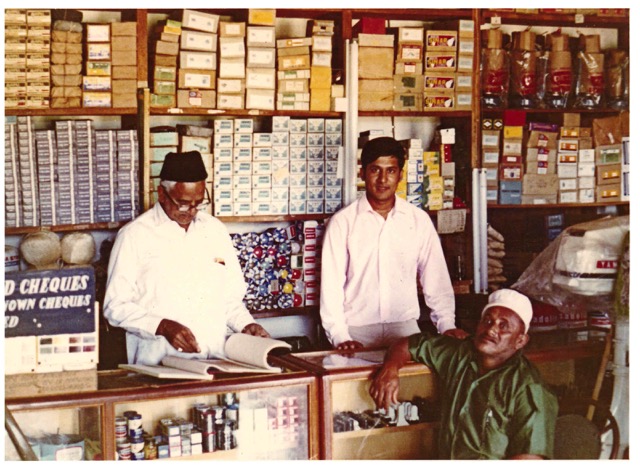

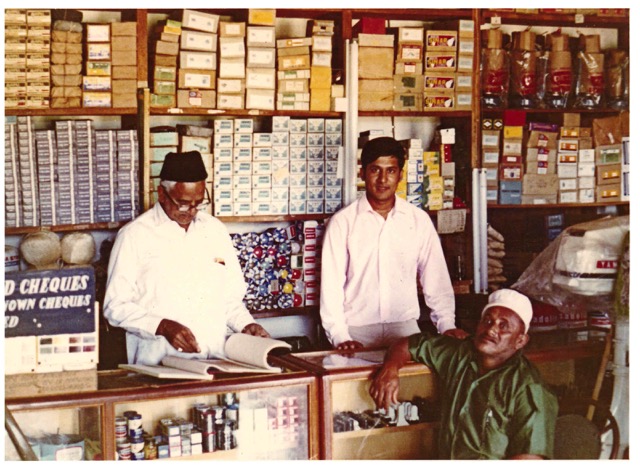

Dukawallah in Uganda.

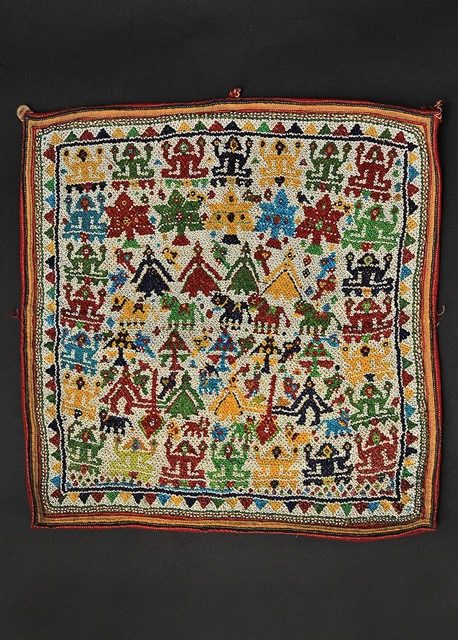

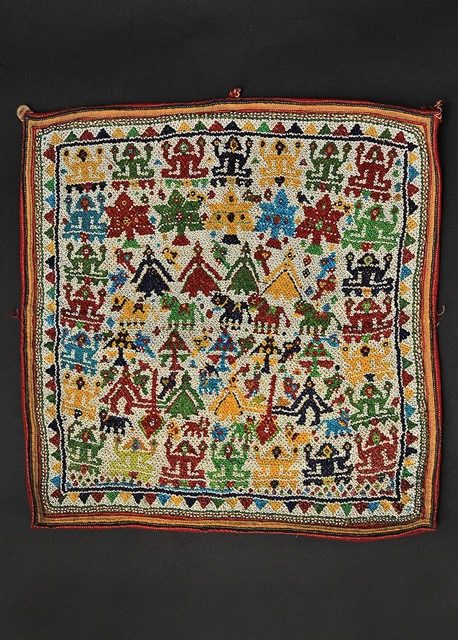

A vibrant display of textiles, metalwork and other materials captures the resilience and the creativity of these displaced Gujarati communities, and shows both how they strove to preserve the art, language, food, literature and religion of their people and also how these were in turn adapted by the countries to which they migrated. It shows how the ‘dukawallah’, who established shops and stores along the east African train line, went on to set up corner shops and stores in Britain and other Western countries, in the process contributing to the change in shop opening hours that eventually led to Sunday trading. It demonstrates how the culture of the people shrugged off differences in religion and belief (the state of Gujarat, while predominantly Hindu, also had significant Muslim, Sikh, Jain and Zoroastrian populations) and how indeed these differences often refashioned cultural templates, which you can see in particular in the evolution of different textile forms. And it reveals – through its stories of everyday racism, the Grunwick strike and the extraordinary success of certain individuals – aspects of migration and settlement that will be familiar to people from different cultural backgrounds.

Beaded square piece.

Intriguingly, from the Migration Museum’s point of view, many of the decisions made by the two curators of the exhibition, Rolf Killius and Lata Desai, match decisions made in our own exhibitions – and vindicate the approach! Not only have almost all the artefacts on display been loaned to the exhibition by ordinary citizens, but the examples of embroidery and other stitchwork adorning the walls downstairs in the cafe area are also all the product of people who have attended the workshops run as part of the overall exhibition. Many of these pieces have been produced by people who had not stitched anything before attending the workshop. In addition, the oral testimonies that accompany the individual displays represent precisely the kind of spoken record that we aim to develop in our own Migration Museum.

Rajkot Patodu sari.

Gujarati Yatra has received Heritage Lottery Funding allowing it, after April, to migrate to a digital format so that it will be available for a further seven years as an online collection. All oral history interviews, the edited films, photographs and texts will go online on a dedicated website: www.gujaratiyatra.com

The whole display is a wonderful, colourful, affirmative account of the ability of a people to navigate its double diaspora and to keep intact its spirit and its sense of cultural identity. We urge you to go and see it!

1As part of the same exhibition, Croydon Now Gallery showcases oral histories and travelling objects (to 14 April 2018), and there is a sari exhibition in the Clocktower atrium (to 26 February 2018) and an embroidery exhibition in the Clocktower Café (to 27 January 2018).

Gujarati Yatra is open until 14 April February in Croydon Now Gallery, and a season of events has been woven around its six-month residency – family days of art and crafts, talks, film screenings, literary events and dance productions – all designed to show how the Gujarati identity is maintained in the UK. The curators are currently contacting other museums and community organisations in order to tour the exhibition to other places in the UK.

21 December, 2017

The festive season is upon us. According to experts commenting on the subject in magazines and newspapers, it could equally be called the arguing season. A friend in an early Christmas party bemoaned the arrival of her in-laws, bringing with them different opinions on Brexit and other political issues that, sooner or later, led to uncomfortably heated confrontations.

And just two days ago, what started as a really interesting discussion in our house – on why so many men failed to recognise that rape and wolf-whistling were on the same continuum, on the way in which power relationships skewed jokes and banter, on whether it was ever acceptable to use racial identity to comic effect – morphed into one of those confrontational exchanges from which at times it feels there’s no coming back.

© Scott and Borgman

And it got me thinking, in an end-of-year valedictory fashion, why it was that discussions, arguments and debates these days so quickly became polarised, and the position taken by the opposing individuals so firmly entrenched. (And is it just ‘these days’? Was it always like this?) What starts out as an exchange of views transmutes into an exchange of fire, and people’s positions end up ludicrously exaggerated – as Hella Eckardt’s recent blog illustrated, in relation to Roman Britain. People at either end of the spectrum insist on the absolute truth of their position with a strident vehemence that doesn’t represent the reality – which is that all of us, bar the most extreme fanatics, recognise the possibility of alternative positions even when firmly convinced of our own. But rather than examine the evidence, listen to whether the other speaker brings something new to the debate that might cause us to reconsider, it suddenly seems more important at any cost to win this argument, to prove that our position is right and the other’s wrong.

Is this failure to discuss and the associated need to win spawned by the structure of our institutions? The adversarial position is hard-wired into our legal system, for example, and also into Parliament (at least, certainly the House of Commons); it used to, and may still, be at the heart of university research and debate; and it’s of course the basis of all sporting activity. It’s clearly not unique to the UK (the US displays it in spades) but is it uniquely Anglo-Saxon, or European, or Western? Are there countries and cultures where winning an argument is less important than hearing what everyone has to say?

These questions lie at the heart of what we are attempting with the Migration Museum. If our concern was to win the argument (whatever that might be) or show other people the error of their ways, we would, rightly, be doomed to failure and unworthy of support. But what we are wanting to do is to create a space where people can debate issues of paramount importance without automatically taking up tired and predictable positions and seeing who can shout the loudest. Our strapline – all our stories – was chosen to reflect both the fact that if you scratch the surface of anyone’s family history in Britain, you will find a migration story, but also, crucially, the recognition that everyone has a say in this matter and all have a right to be listened to, even if some might find their views unacceptable.

It’s not a new year’s resolution, because it’s been the nub of what we’ve been doing since the beginning, but listening and allowing the spectrum of opinions to be heard without it all descending into the weary Twitterati scrimmage of rancour and animosity – that’s what we’ll continue to do in 2018. With Brexit, Trump and other factors casting their divisive, polarising shadow, it seems more important than ever. So, if you’re raising a glass over this festive period, here’s to listening, not fighting.

To all our readers and followers, have a really good break over the festive period, and see you again in the New Year.

3 December, 2017

The Migration Museum Project is blessed with a large team of fantastic volunteers, without whom we would find it hard to function and impossible to run our events and exhibitions. Assunta Nicolini is one such volunteer, and her discussions with visitors to our current exhibition, No Turning Back, have got her thinking about a number of issues that she feels are raised by the display. This blog is the result of her thoughts and discussions around two of the seven moments of the exhibition: the arrival in this country of Huguenot refugees after 1685, and the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905.

No Turning Back: Seven migration moments that changed Britain introduces visitors to powerful artworks and archive images carefully interwoven to create a narrative that brings together past and present. It is within history that we so often find the key to understanding many of the social realities we inhabit today.

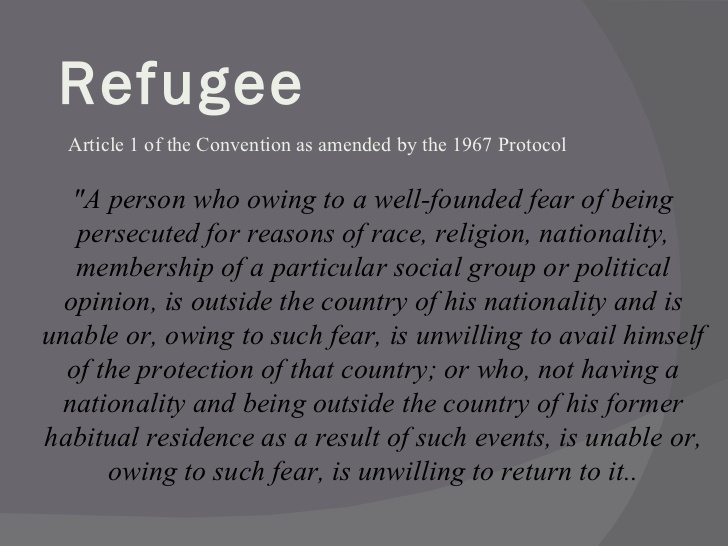

Migration is no exception. One of the seven moments shown in the exhibition, the year 1685, holds a particular relevance in the understanding of today’s migration dynamics.It was the year that France made Protestantism illegal, precipitating the arrival in Britain of about 50,000 French Protestant Huguenots. Centuries before the drafting of the Refugee Convention (1951), and with no legal framework in place establishing roles and responsibilities towards people escaping persecution, the term ‘refugee’ was introduced into the English language through the French Huguenots arriving on British soil in search of protection (refuge). It took about three centuries, a series of major humanitarian crises and, ultimately, the horror of the Holocaust for the international community to establish a legal framework aimed at giving protection to people fleeing persecution.

Article 1 of the United Nations’ 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

The history of the Huguenots in Britain is not, however, just about one of the largest refugee groups to seek safety and protection in this country. Their life experiences were not simply defined by their ‘refugee-ness’; on the contrary, their arrival and settlement offer just as important insights into the realities of migration.

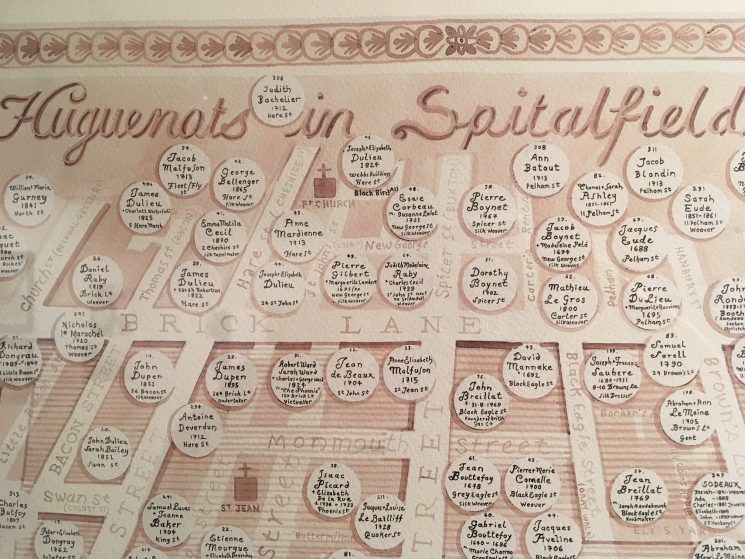

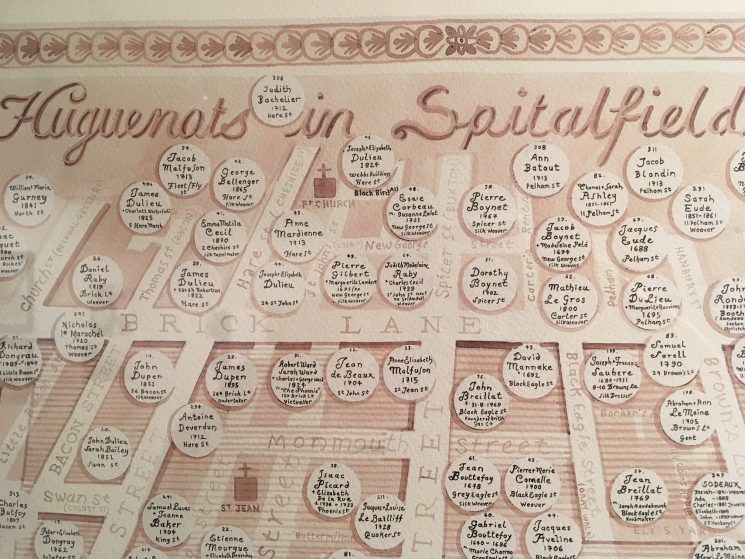

In the exhibition, Adam Dant’s delightful map representing this historical moment takes the curious eye of the visitor through a detailed drawing of the streets surrounding East London’s Spitalfields Market. Surnames of French origin are circled to indicate where the Huguenots were to be found. As visitors adjust their eye to these several locations, they then notice a further, more crucial detail. Surnames are accompanied by ‘professions’, mainly artisanal, such as weavers, clockmakers and silk merchants.

A detail from Adam Dant’s ‘Huguenots in Spitalfields’. A range of professions are readable in these circles, for example: ‘silk weaver’, ‘undertaker’, ‘victuailler’, ‘reed maker’ and ‘gent’. © Adam Dant

Such detail is crucial as it allows the visitor to expand their understanding of who these people were, beyond the one-dimensionality of their ‘refugee-ness’. Being given protection in Britain was not the end of the Huguenots’ ‘migration journey’ – settling and restarting their lives, as well as providing for their families, was just as important. Historical archives tell us that, although the Huguenots left France clandestinely and at short notice, taking little with them and with limited time for planning ahead, they were nevertheless aware that certain destinations were better than others. London, for example, offered not only protection but also great opportunities for employment and hence a better place to settle.

You don’t need to be an expert to spot the striking similarities with contemporary experiences of migration. Today’s refugees are no different from those of centuries ago – like them, they are human beings who, in order to have a life beyond survival, need to work. Obvious though this point is, the current obsession in the media and parliament is the apparent distinction between ‘refugee’ and ‘economic migrant’.

It is possible, however, to make such complexity simple, and to offer an accessible understanding of such migration dynamics. Migration experts have been drawing attention to the fact that immigration statuses – the classification of refugee, migrant or asylum seeker, for example – are never fixed but on the contrary are dynamic and mobile.1 Rigid legal categories labelling individuals either as migrants or refugees have become increasingly obsolete, as they fail to reflect the personal and global realities of contemporary migration.2 The stories of refugee-migrants themselves consistently show that people might start their journey as refugees but, like the Huguenots, become economic migrants later on. Scholars have widely recognised that contemporary migration is defined by its mixed nature and by continuity, rather than an opposition between forced and voluntary migration (see this video for Dr Nicholas van Hear’s clear outline of this matter).

The overlapping and mobility between immigration statuses is an aspect that was overlooked at the the time the Refugee Convention was drafted. Understandably, soon after the Second World War, the concern of the international community was focused predominantly on making sure that persecuted people would be protected outside their home countries. Economic migrants, on the other hand, could not benefit from a specific legal framework protecting their rights, since the ‘voluntary’ dimension of their migration implied they took responsibility for their own protection.

In recent decades, however, a greater emphasis has been placed on additional legal frameworks aimed at correcting the shortcomings of the Refugee Convention, in particular those based on International Human Rights law. A rights-based approach can in fact not only provide a framework for the protection of economic migrants but also enhance refugees’ protection, while at the same time establishing the universal human right to seek asylum.

Despite the availability of different legal frameworks governing migration and ‘refugee-ness’ today, there is no agreed position in policy making, advocacy and public opinion. Public opinion is characterised by narratives of ‘good and bad’ refugee-migrants, of ‘deserving and undeserving protection’, and of ‘inclusion and exclusion’. Refugees are mostly perceived as victims, but the moment they display willingness to economically improve their lives they are automatically seen as economic migrants and hence as undeserving of protection and support.

Satire on the Aliens Act – drawing of Britannia turning away a group of refugees who have just disembarked at a port, 1906. Part of the Migration Museum Project’s ‘No Turning Back’ exhibition. Image courtesy of the Jewish Museum.

Far from being new, this narrative partly finds its roots in another pivotal migration moment shown in the exhibition – 1905, when the Aliens Act was passed in Britain, the first legal framework regulating migration and based on the notion of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ immigrants. The Aliens Act was the result of rising nationalism based on disproportionate fear about newly arrived refugees, mainly Jews, and migrants of Asian origins. A satirical drawing from the time, showing Britannia saying ‘I can no longer offer shelter to fugitives; England is not a free country’, aptly describes the feeling of rejection felt by Jewish refugees. Another pamphlet from the archives directs the visitor’s attention to the fact that rejection was felt not only by refugees but also by immigrants, with trade unions attempting to dismantle the unfounded belief that migrants were competitors in the job market and bad for the British economy. Through the various details of this migration moment, the visitor is also encouraged to think about the importance of keeping labour migration channels open to refugees today.

History reminds us that looking at migration through rigid binaries of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’, ‘deserving’ and ‘economic’, risks reinforcing a dangerous divide that often underpins much of public opinion and policy making. What we witness today and the stories that migrants and refugees tell us bear a profound resemblance to the past and urge us to consider that a refugee-migrant should not be seen as a threat but rather as an asset to Britain and host countries in general.

1 See, for example, Schuster, L (2005) ‘The Continuing Mobility of Migrants in Italy: Shifting between Statuses and Places’. Oxford: COMPAS and Bloch (2011)

2 Zetter, R (2007) ‘More labels, fewer refugees: remaking the refugee label in an era of globalisation’, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 20, Issue 2, 1 June 2007, 172–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem011