Archives

23 March, 2018

On Tuesday 13 March, Historic England conferred Grade I listed status on the Shah Jahan Mosque in Woking, Surrey, which thereby became the first mosque to receive this status in the country.

The Shah Jahan Mosque, Woking. © Heritage England

There had been other registered mosques in the UK before the Woking mosque, the earliest on record being the Liverpool Muslim Institute, which was established in 1887 in a street called Mount Vernon Terrace, and moved to Brougham Terrace in 1889. Brougham Terrace is considered to be the first fully functioning community mosque, but the Shah Jahan Mosque, which was established in the same year (1889), was the first purpose-built mosque in this country, indeed in northern Europe.

There are no end of fascinating things about the Shah Jahan Mosque, which owes its name to its principal funder, the female ruler of the Indian princely state of Bhopal, the Sultan Shah Jahan Begum. One is the obvious surprise of its location in Woking, a commuter town in Surrey, 30-odd miles from London, and not the obvious focal point for Islamic worship or study. Another is that, when the mosque was established (in 1889), there were very few Muslims among its worshippers who had been born outside the country: most were white British men and women who had converted to Islam, among them (as listed on the mosque’s website) Lord Headley, Marmaduke Pickthall, David Cowen, Charles Buchanan Hamilton (nephew of James Hamilton, the President of the United States of America), Sir Archibald Hamilton (cousin to King George) and the Shaykh of the British Isles, Abdullah Quilliam, who had been born William Henry Quilliam.

A third interesting aspect of the Shah Jahan is that it was designed by an English architect, William Isaac Chambers, who had moved to Dublin in the 1870s (building an elaborate villa for himself there) but who had then returned to England in the mid-1880s to set up an architectural practice in Woking.

The main entrance to the Shah Jahan Mosque, Woking: a landscaped garden leads to an entrance portico. © Heritage England

And a fourth fascinating aspect of the mosque is that the person principally responsible for its establishment was a British-Hungarian Jew, Gottlieb Leitner. Leitner acquired the site of the mosque (previously the site of the Royal Dramatic College) with the intention of building a mosque, a synagogue, a temple and a church in the same area. His early death, at the age of 59, left these plans unfulfilled, and his heirs sold off the land earmarked for the synagogue and the temple; the church was the only other building built – it still stands today as St. Paul’s Church, on (fittingly) Oriental Road.

Leitner was an extraordinary man, prodigiously gifted in languages: he was said to have been fluent in at least nine languages by the age of 10 and, later, to have extended this fluency to 10 more languages, while also being able to get around in a further 30. He spent more than 20 years in India, mostly in the Punjab, where he helped to found the University of the Punjab, and where he co-wrote a two-volume History of Islam in Urdu. He returned to Britain in 1881, with the firm intention of establishing a centre for the study of Oriental languages, the first of its kind in Europe. When he died, in 1899, he was acknowledged as the world’s pre-eminent orientalist (a description that nowadays would be qualified with the phrase ‘in the West’), yet, despite being born a Jew and having devoted much of his life to the study of Islam, his burial was undertaken in St Paul’s Church.

Having depended so intensively on Leitner’s passion and involvement, the Oriental Institute fell into disuse after his death, and the mosque is now the only surviving memory of this remarkable man’s ambition. It is great news that the architectural and symbolic importance of this ‘extraordinarily dignified little building’ (as Nikolaus Pevsner put it) has finally, just under 130 years after its establishment, been recognised in its Grade I listing.

Shahed Saleem, a long-time friend and supporter of the Migration Museum Project, has been instrumental in the listing of the Shah Jahan Mosque. His recently published book, The British Mosque: An Architectural and Social History (published by Historic England) includes these accounts of the mosque:

With Chambers’ [the architect’s] penchant for architectural flamboyance, his mosque liberally embraces Mughal architecture, the style developed by the rulers of much of South Asia from the 16th to the 18th centuries. Earlier Mughal buildings in and around Delhi display a certain classical rigour and formality. This evolved in later Mughal buildings further south around the Deccan region of India into a more expressive architectural language. While the main elements of a central large dome, large central arched portico and smaller flanking bays with arched doorways or niches remain throughout the Mughal period, in the later buildings these become noticeably more sculptural. Chambers had taken and adapted this architectural language at Woking, with a dome that is an evolution of the well-recognised onion shape into a much more spherical object.

The Shah Jahan Mosque, Woking. © Heritage England

The Shah Jahan Mosque also seems to take the language of late Mughal architecture in a Gothic direction in the portico’s ogee archway and the trefoil-shaped arch over the main entrance door. The smaller domed cupola corner turret is a feature that occurs throughout the Mughal period. The stepped battlements, however, follow a style that originate in early Fatimid architecture found in Egypt in the 10th century. These seem to be the only real instances where the architect has cross-referenced architectural languages in an otherwise faithful use of Mughal stylistic heritage.

Interior view of the dome of the Shah Jahan Mosque. © Heritage England

The Shah Jahan Mosque almost perfectly captures the spirit of 19th-century ‘Orientalism’. This was a time when, for curious Europeans, there was a mysterious and fantastical place called ‘the East’. It was a place of strange customs, flamboyant dress and exotic women, encapsulated in a vast genre of Orientalist paintings depicting the East in theatrical ways. The Woking Mosque could be considered as the architectural equivalent of this Orientalist fantasy.

[. . . ]

The Woking Mosque has the longest and one of the most significant histories of any mosque in Britain. Architecturally, it represents the very first manifestation of the mosque as a building type, and thus the representation of Islam, in Britain and indeed in Western Europe. The mosque enabled a Muslim social organisation to develop, which played a fundamental role in the evolution of British Muslim institutions and in the establishment of Islam in Britain.

The great social changes that followed World War II, and the seismic demographic shifts in the Muslim populations of Britain, did not pass this secluded mosque by. As social change came to Woking, the role of the mosque shifted from national beacon to place of local community need, and its administration and outlook came to reflect this new reality.

Restored and listed, the Woking Mosque is a secure part of the nation’s heritage. As Muslim communities and cultures become generationally embedded in Britain, and as their histories are explored and made manifest, the Woking Mosque will always be revisited as a key starting point of Muslim architectural and institutional history in Britain.

from Saleem, S (2018) The British Mosque: An Architectural and Social History.

London: Historic England.

The Migration Museum Project would like to thank Shahed Saleem for permission to quote from his book and Historic England for allowing us to use photographs from their collection.

15 September, 2014

By a happy coincidence, our new exhibition, Germans in Britain, opens at the German Historical Institute on Thursday 18 September, the day on which George 1 arrived in England from Germany three hundred years ago.

George hadn’t been the obvious successor to Queen Anne, when she died in August 1714: there had been more than 50 others with a stronger hereditary claim, but all of them were Catholic, and the Act of Settlement in 1701 had established that no Catholic monarch would ever take the throne again. George was the first Protestant in line to the British throne.

Like most migrants before and after him, George had something of a mixed reception. More than a million people are said to have turned out to welcome the new King as he made his way from Greenwich to Westminster. But not everyone joined in this celebration. At the time of his coronation there was rioting in more than 20 towns around the country, and he continued to divide opinion in the 13 years of his reign, with many people making fun of him for his inability to speak English.

Like most migrants before and after him, George had something of a mixed reception. More than a million people are said to have turned out to welcome the new King as he made his way from Greenwich to Westminster. But not everyone joined in this celebration. At the time of his coronation there was rioting in more than 20 towns around the country, and he continued to divide opinion in the 13 years of his reign, with many people making fun of him for his inability to speak English.

That said, he steadied the throne, established a dynasty (the Hanoverian dynasty) that continued to the reign of Queen Victoria, and his reign triggered a period of prosperity and rapid change, overseeing the beginning of the industrial revolution and the emergence of Great Britain as a global power.

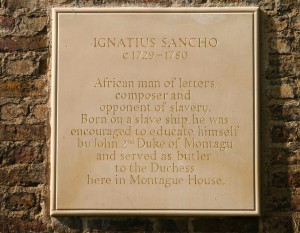

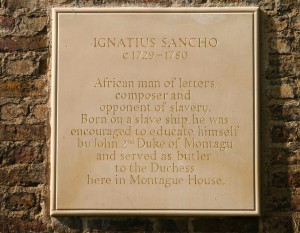

The Royal Steps, which George 1 walked up after disembarking from the Peregrine at Greenwich, lead up to the gates of the Royal Naval College in Greenwich and are, effectively, where Greenwich Park runs into the river. At the top of the park a plaque on the western wall, just behind the Ranger’s House, commemorates a different kind of migrant, though one living in the same century. Ignatius Sancho – born, not on the Peregrine, but on a slave ship – is widely considered to be the first Black Briton to vote in an election as well as the first to be given an obituary in the British press. He was highly valued and trusted by the Montagu family, for whom he worked for much of his life and who were influential in his education (the first Duke of Montagu lent Sancho books from his personal library, to the horror of the three sisters for whom Sancho was then working in Greenwich).

The Royal Steps, which George 1 walked up after disembarking from the Peregrine at Greenwich, lead up to the gates of the Royal Naval College in Greenwich and are, effectively, where Greenwich Park runs into the river. At the top of the park a plaque on the western wall, just behind the Ranger’s House, commemorates a different kind of migrant, though one living in the same century. Ignatius Sancho – born, not on the Peregrine, but on a slave ship – is widely considered to be the first Black Briton to vote in an election as well as the first to be given an obituary in the British press. He was highly valued and trusted by the Montagu family, for whom he worked for much of his life and who were influential in his education (the first Duke of Montagu lent Sancho books from his personal library, to the horror of the three sisters for whom Sancho was then working in Greenwich).

From his reading, Sancho developed a lifelong passion for poetry, literature and music, and became a writer himself, publishing two plays and a book called A Theory of Music. Although exposed to a fairly predictable daily litany of racist abuse, he was cheerful and popular, and had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances from the arts and politics. His correspondence with the novelist Laurence Sterne (with whom he formed a long friendship) became a cornerstone of eighteenth-century abolitionist literature and led to the publication of his letters after his death.

From his reading, Sancho developed a lifelong passion for poetry, literature and music, and became a writer himself, publishing two plays and a book called A Theory of Music. Although exposed to a fairly predictable daily litany of racist abuse, he was cheerful and popular, and had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances from the arts and politics. His correspondence with the novelist Laurence Sterne (with whom he formed a long friendship) became a cornerstone of eighteenth-century abolitionist literature and led to the publication of his letters after his death.

Thursday 18 September may be the anniversary of the arrival on our shores of one of these migrants only, but it seems fitting that the same stretch of land should bear witness to the two different but similar stories of George 1 (Elector of Hanover and King of Great Britain and Ireland) and Ignatius Sancho.

Germans in Britain is on display in the German Historical Institute from 18 September to 24 October and thereafter on tour at various venues. See the website for details.

Germans in Britain is on display in the German Historical Institute from 18 September to 24 October and thereafter on tour at various venues. See the website for details.

Andrew Steeds

14 March, 2018

In a second blog for us, Assunta Nicolini, one of our regular volunteers, talks about how two of the seven moments in our current exhibition, No Turning Back, have caused visitors to raise questions about the complex relationship between race, migration and racism. Assunta is writing here in a private capacity.

A year and a half after the EU referendum, in which concerns about immigration played a major role, debates continue about what Britain’s future migration policy should look like.

In the lead-up to the release of a new Immigration White Paper framing a future British immigration system, the Home Affairs Committee published a report – Immigration Policy: Basis for Building Consensus – highlighting, among other things, current public attitudes to the issue of migration. It is encouraging to read that, despite the apparent polarisation of views about migration, the majority of the British public remains very open to engaging in a constructive, open debate on the subject.

Debate has been at the heart of all the Migration Museum Project’s exhibitions since ‘100 Images of Migration’, in which this photo, ‘Speaker’s Corner, Hyde Park, London, October 2009’, appeared. © Guy Corbishley

As a frequent and active volunteer at the Migration Museum, I have witnessed first-hand this willingness among visitors to our current exhibition, No Turning Back: Seven Migration Moments that Changed Britain, to engage constructively with the subject of migration. Regardless of visitors’ background in terms of race, gender, age or migration story, one attitude stands out: the desire to learn about the migration history of this country.

Guiding the public through the selected seven moments – spanning centuries – means also that visitors are prompted to constantly connect and compare past events with present realities, and to find out more about some of the complex factors that shape migration. By engaging with debates about the difference between economic migrants and refugees, for example, or the complex relation between racism, race and migration, visitors are able to find their own answers, share their thoughts and opinions, and respond to questions and contribute to conversations started by other visitors to the exhibition. It’s through this type of understanding that engagement becomes constructive.

To use just one example, the current exhibition encourages visitors to think about how British migration, historically, has been framed by race – to familiarise themselves with one of the most important themes in contemporary migration studies, the racialisation of migration. At its core, racialisation focuses on the process behind ideas of race and how they adapt to specific contexts and times. It allows us to understand how race, which is socially constructed, is used to exclude, discriminate and subordinate those who are considered inferior by a certain dominant group. From the colonial era onwards, ‘dominant groups’ in Britain have continuously racialised and cast as outsiders ‘non-Brits’ on the basis of skin colour or religion. What this means is that, regardless of who ‘the Other’ is, whether non-white or non-Christian, ‘outsiders’ are placed in a condition of inferiority. This mechanism is the main driver of what we know as racism.

A visitor stands in front of Liz Gerard’s ‘The Chart of Shame’. © Migration Museum Project

The exhibition also explores the role of the media in shaping public opinion and reinforcing links between migration, race and religion. The Chart of Shame, a work by former journalist Liz Gerard that visitors can find in the 1905 ‘moment’ of the exhibition, displays all of the front page migration stories published in British national newspapers in 2016 in the form of a bar chart. Even if they are often not surprised at what they see, visitors are nevertheless visually shocked by the amount of attention given to migration; a closer look then reveals the often negative, racialised language used in so much of the coverage. You don’t need to be an expert in text analysis to count how many times derogatory terms referring to migrants and refugees are used, and to begin to think about how the use of this language feeds into and contributes to divisive narratives. The artwork, and the context in which it is presented, alongside a quote from Tony Gallagher, editor of the Sun, rejecting the suggestion that newspapers are responsible for creating divisive and hostile migration myths, gives visitors an opportunity to take in a large amount of data in one moment and to think critically about the role of the media in migration debates.

It is often at this moment in the exhibition that visitors display visible disappointment with, and even resentment towards, what they perceive to be a biased media, fuelling division in British society. Some ask, ‘What can we do? I’m not a racist, many people don’t even know their opinions on migration are racist . . . ’ – to these questions the exhibition allows visitors to discern some answers, balancing moments of hostility and racism with times when the public in Britain stood up, united and fought racism. In the late 1970s, for example (and one more of the seven ‘migration moments’), when racial tension was particularly high, people took to the street in thousands, united under the banner of Rock against Racism. For this migration moment (1978) there is a wealth of archive material and artworks that has prompted visitors to reflect on the racist attitudes of much-admired public figures such as Eric Clapton at the time, the role that grassroots cultural movements can play in changing attitudes, and to consider the need for similar grassroots movement now. Statements hanging from the ceiling provide first-hand testimony of many at the time. It is fascinating to see the reaction of younger visitors, many of whom were unaware of this historical moment, as well as those of people actively involved at the time. Whether they are learning or remembering, it feels like the exhibition is having an immediate, tangible impact.

No Turning Back is indeed a powerful exhibition, effective in addressing crucial themes around migration and encouraging the public to learn, engage and develop informed opinions. Through historical narratives and artworks visitors are given the tools to engage with and challenge many contemporary migration myths and misconceptions. In doing this, the exhibition contributes to the recommendations provided by the latest Home Affairs Committee report: ‘We cannot stress enough the importance of action to prevent escalating division, polarisation, anger or misinformation on an issue like immigration. To fail to address this risks doing long-term damage to the social fabric, economy and politics of the United Kingdom.’

Having a Migration Museum in which Brits and non-Brits alike can learn about and interact with this country’s history of migration is more important now than ever before – particularly when the debate around migration is so intense and people are showing a willingness to engage constructively.

Assunta Nicolini is working on migration and asylum in conflict areas while completing her doctoral studies at City University, London.

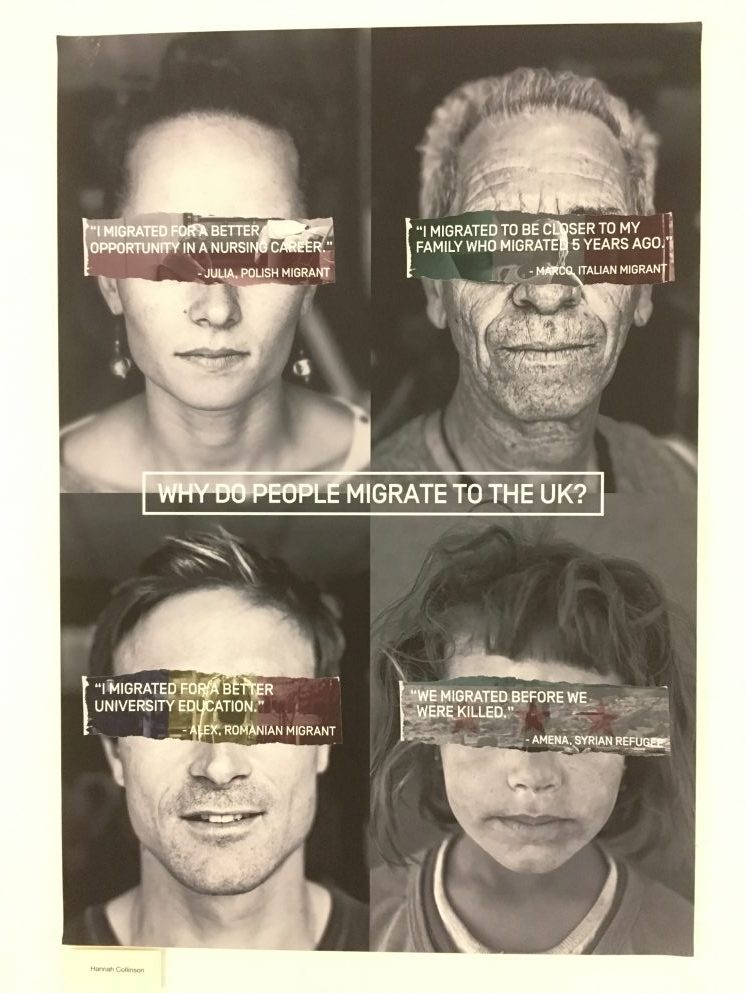

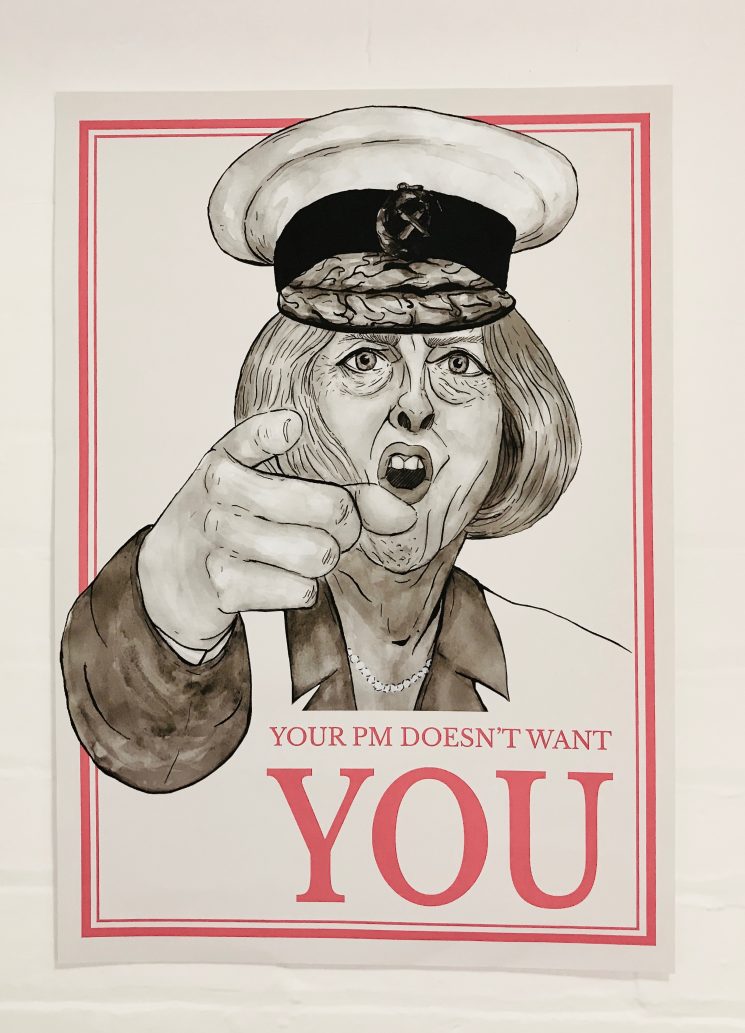

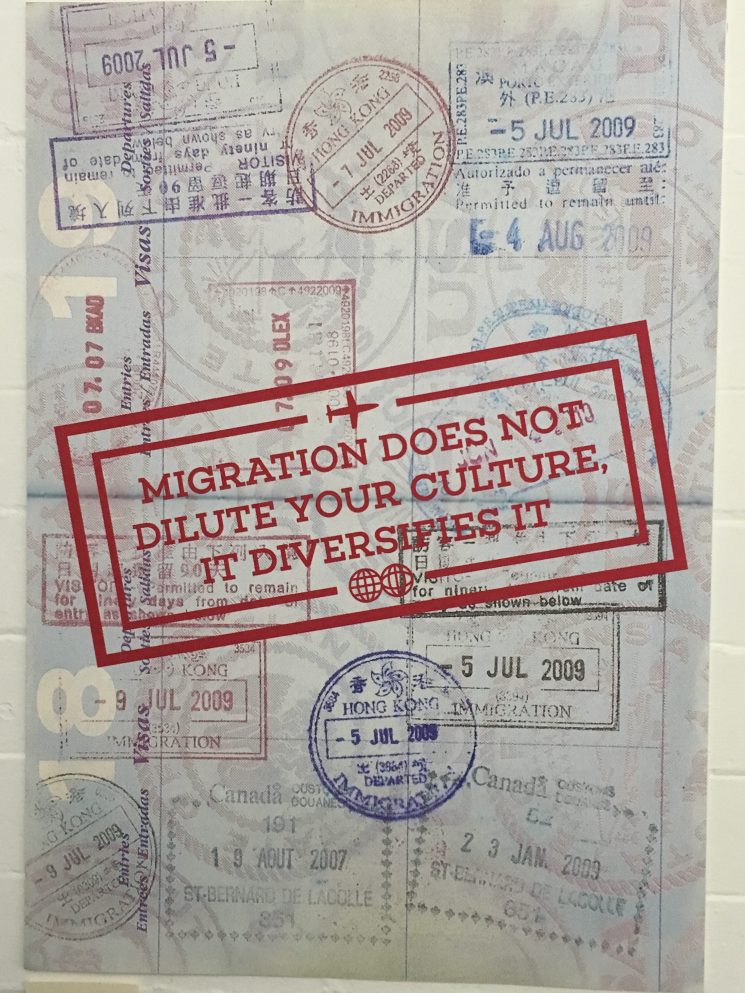

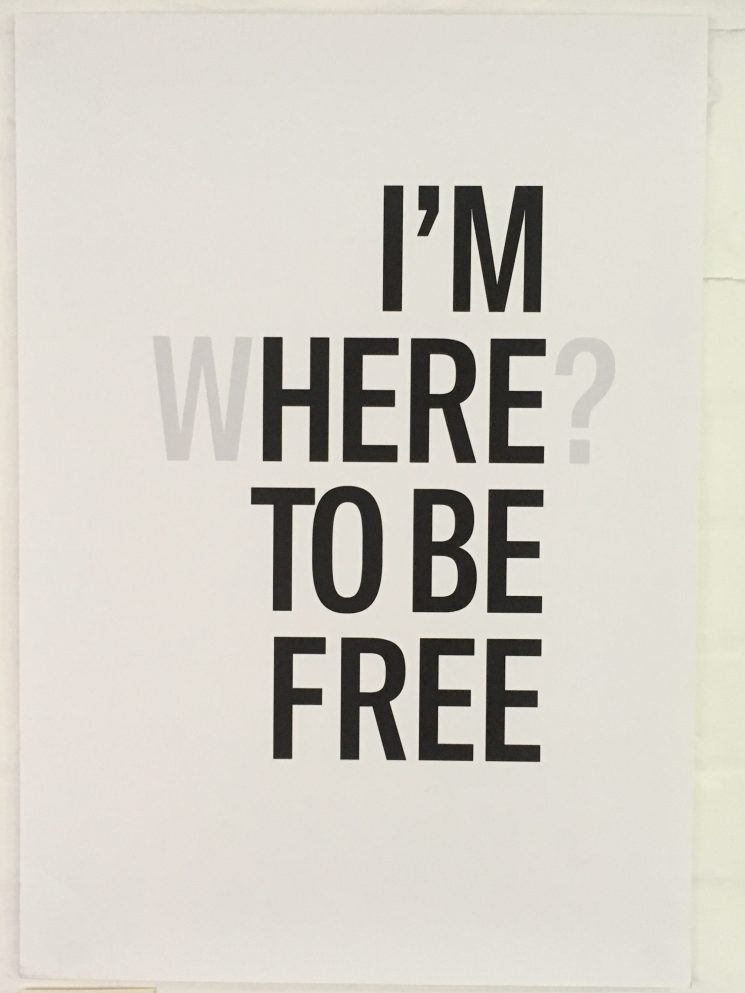

26 January, 2018

In a collaboration between the Migration Museum Project and the University of Hertfordshire, second-year graphic design and illustration students were tasked with designing a poster in response to the question: ‘What does migration mean in the UK today?’ Chosen by Curator Sue McAlpine, a selection of these posters is currently on display along the stairwell and entrance corridor to the Migration Museum at The Workshop.

Kerry William Purcell, Senior Lecturer in Design History at the University of Hertfordshire, explains the background to the project as well as presenting some of the posters produced by his students.

Migration Museum Project

—

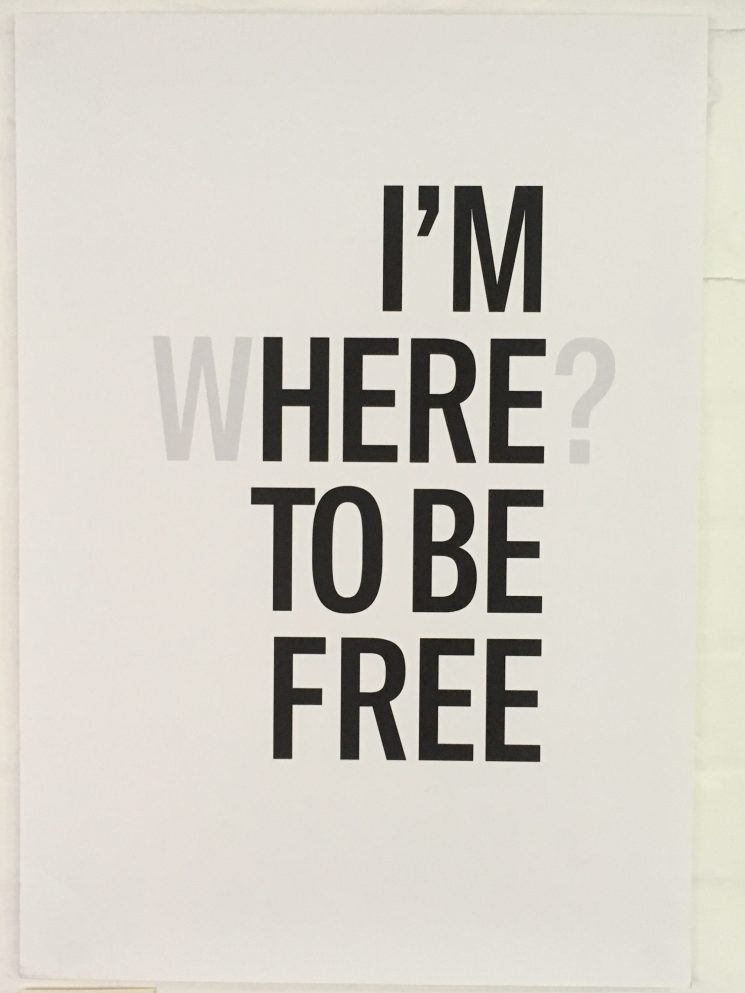

What does it mean to leave everything behind to start again? What happens when the problems of victimisation, lack of work, or exploitation – the very reasons that compelled one to migrate in the first place – are experienced in a newly adopted country?

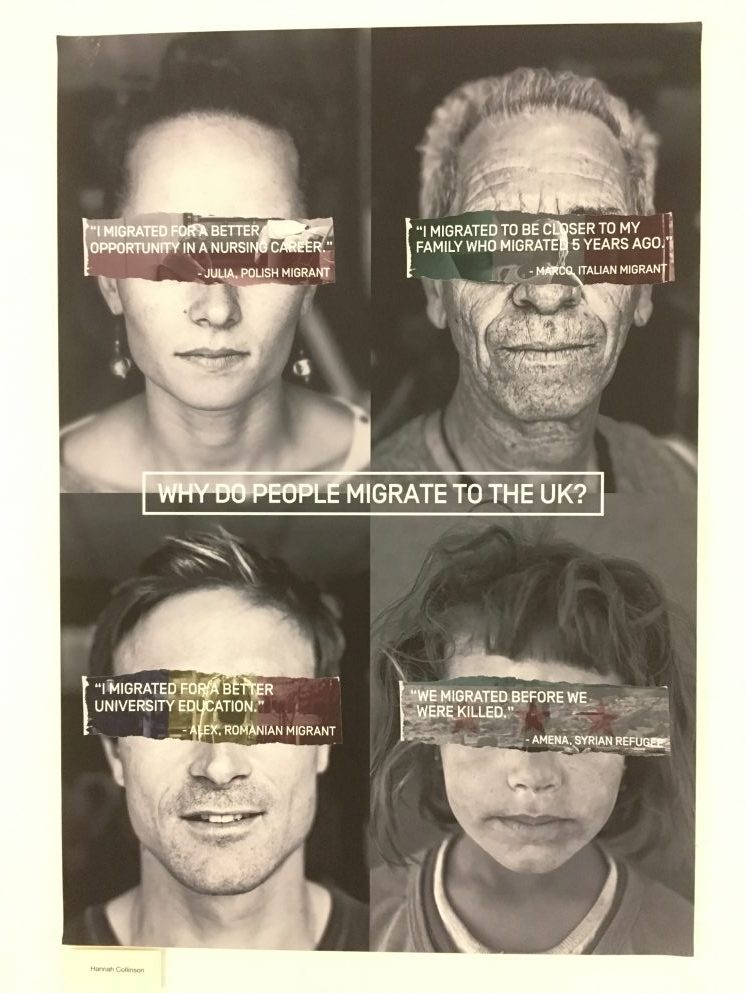

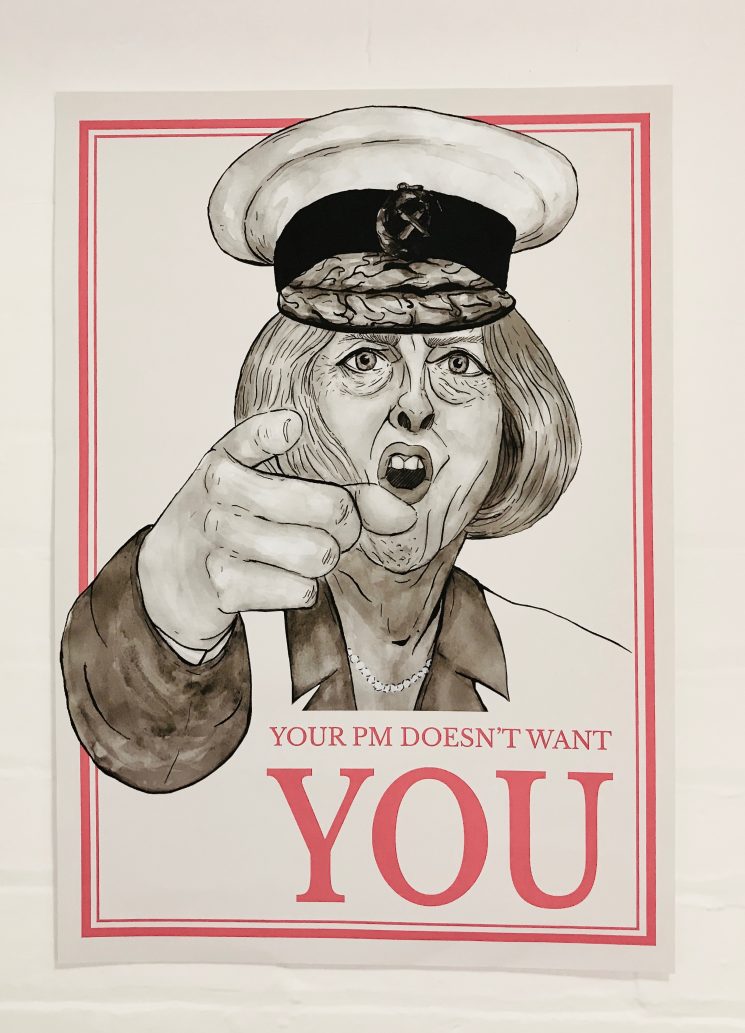

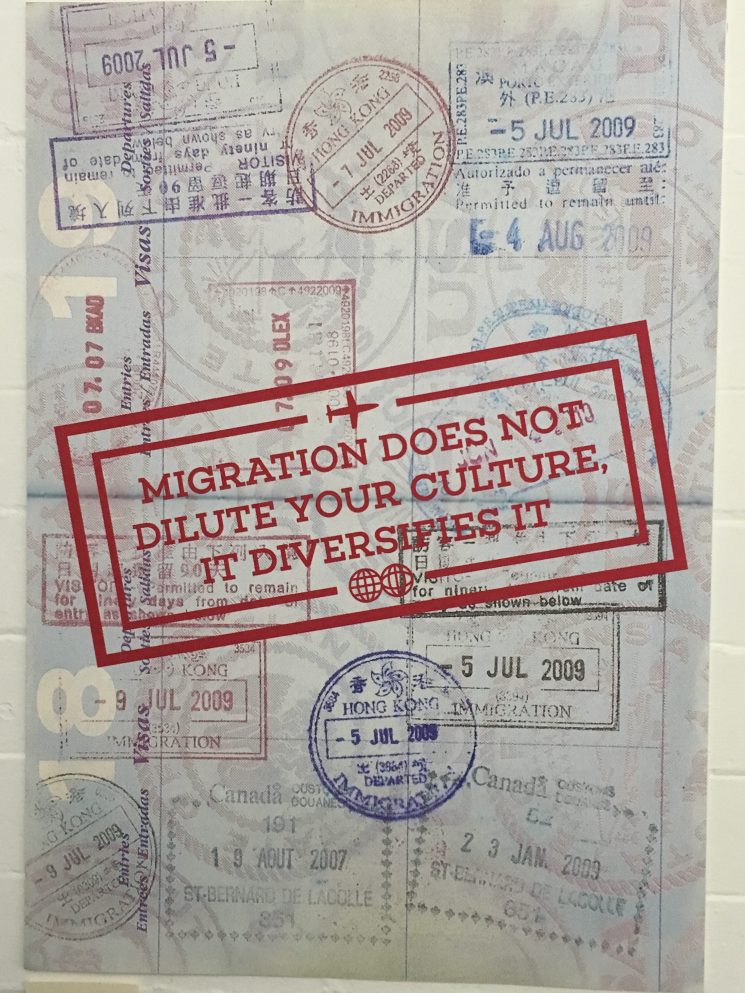

Faced with the question of ‘What does migration mean in the UK today?’, second year University of Hertfordshire (UH) graphic design and illustration students were tasked with representing such issues in a single poster. Working individually, the project ran for two months and was part of a larger brief where the students also wrote essays addressing a range of ethical issues in design.

The brief for this work was intentionally broad. And as can be seen from this selection, the outcome was a wide range of responses, from the personal and autobiographical, to news stories, to designs that touch on the aims and ambitions of the Migration Museum itself.

Hannah Collinson

Many UH students are either migrants themselves, or the children/grandchildren of migrants. As such, for some, the project opened a space to speak to family members about their migratory experiences. For others, it was a chance to respond to the dominant tabloid narratives of ‘othering’ that have been so prevalent in recent press coverage of the current ‘migration crisis’.

In this digital age, one can often forget how the poster has long been a vehicle for the dissemination of (mis)information about the subject of migration. Whether as government propaganda, or grass-roots campaigns seeking to challenge the mistreatment of migrants, the poster has the ability to condense a complex range of issues into a single graphic space. As many of these student designs reveal, it still remains a powerful visual tool.

Kerry William Purcell is Senior Lecturer in Design History at the University of Hertforshire and Associate Tutor in Cultural Theory at Birkbeck, University of London

A selection of these posters is currently on display along the stairwell and entrance corridor to the Migration Museum at The Workshop, 26 Lambeth High Street, London SE1 7AG. We are open Wed–Sun 11am–5pm (late opening until 9pm on the last Thursday of each month).

Click here for more information on how to find us

—

Danielle Spokes

Vivian Phang-Xin-Yuan

Michael Gillerton

Rahmel Hewitt-Powell

Victoria Plum

Marta Płaczkowska

Germans in Britain is on display in the German Historical Institute from 18 September to 24 October and thereafter on tour at various venues. See the website for details.

Germans in Britain is on display in the German Historical Institute from 18 September to 24 October and thereafter on tour at various venues. See the website for details.