16 April, 2018

PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS EVENT HAS ALREADY TAKEN PLACE. FOR EDUCATION ENQUIRIES, PLEASE CONTACT OUR EDUCATION OFFICER

2 May 2018 | 4pm–7pm (Wed-Sun, late opening last Thurs of each month)

Migration Museum at The Workshop

26 Lambeth High Street, London, SE1 7AG

To attend, please email: liberty@migrationmuseum.org

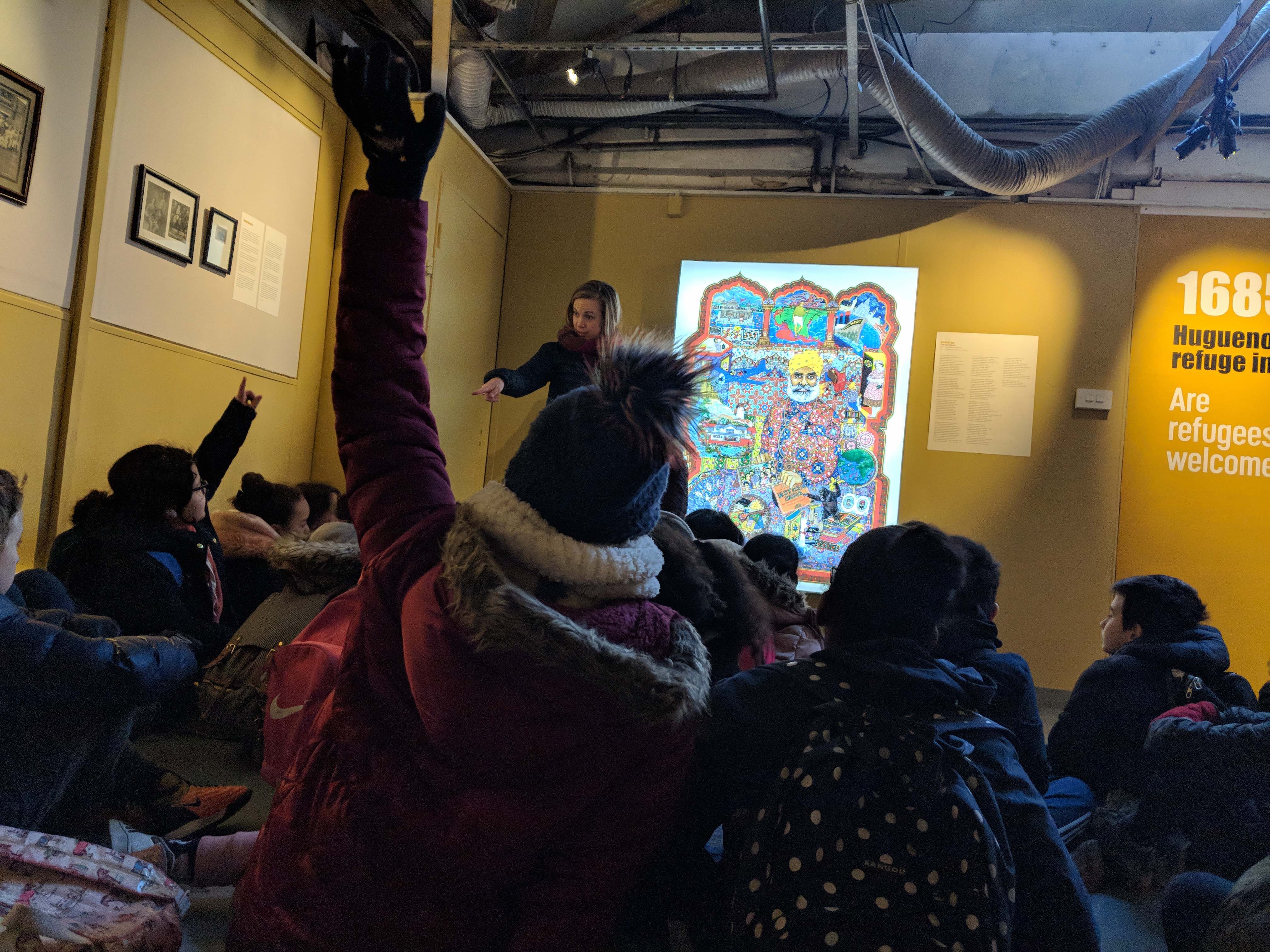

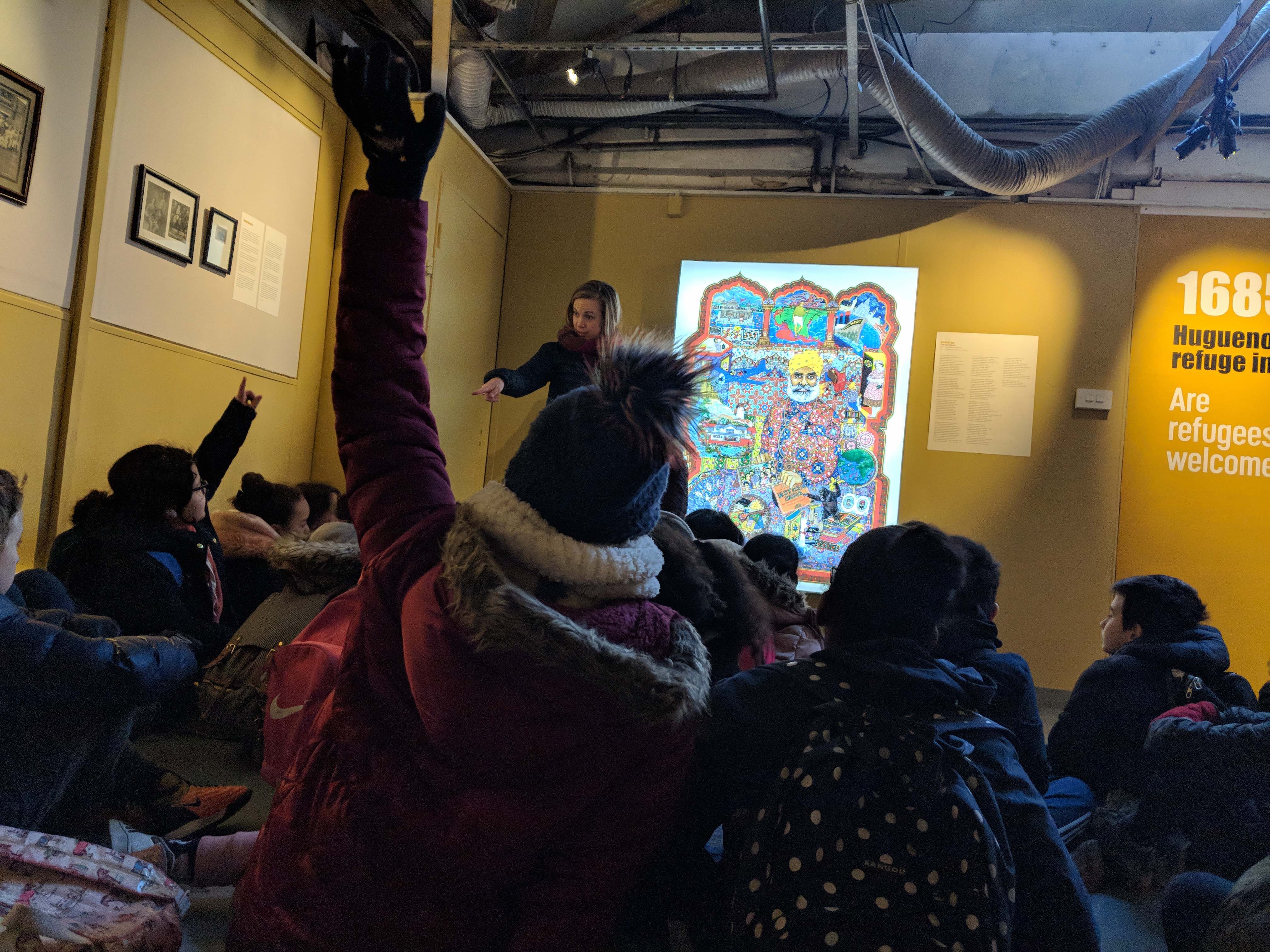

We are hosting a teachers’ evening on Wednesday 2 May 2018.

Teachers from across London and the UK are invited to the Migration Museum at The Workshop to find out all about our education programme related to our current exhibition No Turning Back: Seven Migration Moments that Changed Britain.

This event is primarily aimed at primary and secondary school teachers, but university and college lecturers are also very welcome to attend. If you or a teacher you know would like to come along or have any questions relating to this event or our education programme, please email our education officer, Liberty Melly, at: liberty@migrationmuseum.org

To view and download our teaching resources relating to No Turning Back, please visit our resource bank.

Image © Migration Museum Project

22 June, 2018

A view of the Anglican Church in Black River, St Elizabeth, Jamaica © Tim Smith

This is a guest blog by photographer Tim Smith, a long-standing friend of the Migration Museum Project and contributor to our 100 Images of Migration exhibition. He describes the background to Island to Island – Journeys Through the Caribbean, a new exhibition at Leeds Central Library which runs from 27 June until 27 July 2018.

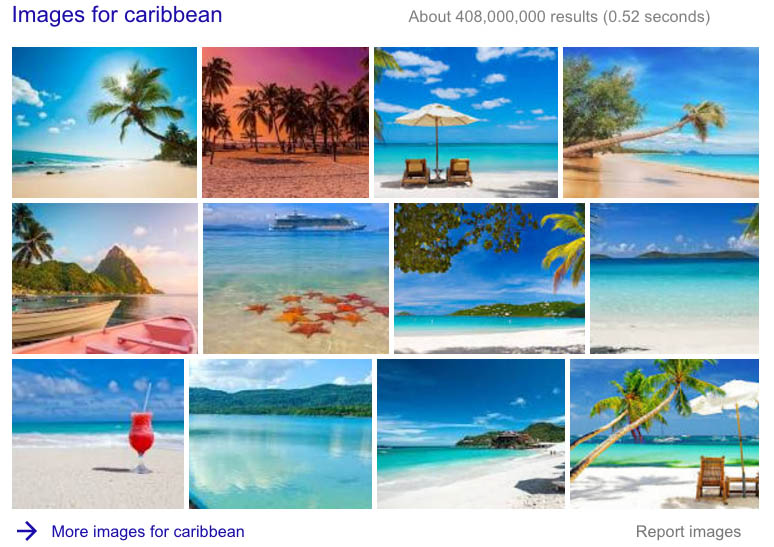

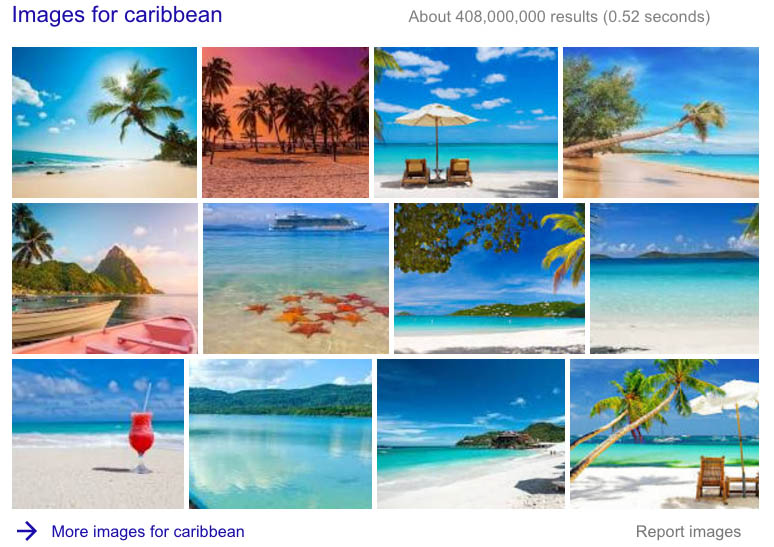

A new exhibition, Island to Island – Journeys Through the Caribbean, runs at the Central Library in Leeds throughout July 2018, but visitors will find it hard to spot many photos of turquoise seas and white sandy beaches lined with palm trees. For that just sit tight, Google “Caribbean Images” and view thousands of photos designed to encourage tourists to visit what is undoubtedly a beautiful part of the world, but which totally ignore the lives of people who live and work there.

First page of search result for Caribbean images © Google

Cutting sugar cane on the Blairmont Estate in the Berbice area of Guyana © Tim Smith

I live in Bradford, work as a professional photographer and have contributed my photographs to several different Migration Museum projects, including their first exhibition 100 Images of Migration. Having grown up in different parts of the world, including the Caribbean, I suspect a nomadic upbringing is one reason why I’m so interested in using photography, film and audio to explore the lives of Britain’s cosmopolitan communities and their links with people and places overseas.

This particular project began in 2010 when I travelled back, for the first time in 40 years, to my childhood home of Barbados. I also visited Dominica, the island from which many of my neighbours in Bradford originate. Returning made me realise that although I can never claim the Caribbean as home, while I was there I did feel at home. This made me determined to investigate other people’s ideas of ‘home’ by visiting other places in the region closely linked to communities in Britain, with the long-term ambition of producing an exhibition that moved beyond the popular stereotypes of ‘The Paradise Islands’.

Since 2010 I’ve been back to Barbados and Dominica, and also visited Antigua, Carriacou, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St Kitts & Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent, and Trinidad & Tobago. Photos of all feature in Island to Island, together with a fascinating series of pictures taken by my father Derek during the 1950s and ‘60s. Shot on slide film they show everyday life in Barbados and other islands that my father visited whilst working for the British Government’s Overseas Development Administration.

A view of Bathsheba, a village on the Atlantic coast of Barbados, during the 1960s © Tim Smith

These slides lay unseen in a wardrobe for decades, but I dug them out and recently scanned a selection for display. Alongside my pictures they show how life has changed over the past sixty years. I’ve been sharing both sets of images with groups of people across Leeds, using them as a spark for exploring their experiences of life both ‘over here’ and ‘over there’. Recording their memories and reflections often brings new life and meanings to the pictures. Some of their words will be used as part of the exhibition along with other people’s stories gathered by Leeds writer Khadijah Ibrahiim, whose poetry also features in the show.

A mural outside Charlestown, the capital of Nevis. The twin island nation of St Kitts & Nevis is the original home of most of the people who migrated from the Caribbean to Leeds during the 1950s and ’60s © Tim Smith

As well as celebrating the light, life and landscapes of the Caribbean, the exhibition is also inspired by a quote from the Jamaican author, Rex Nettleford, who wrote: ‘The apt description of the typical Caribbean person is that he/she is part-African, part-European, part-Asian, part-Native American but totally Caribbean. To perceive this is to understand the creative diversity which is at once cause and occasion, result and defining point of Caribbean cultural life.’ I set out to create photographs which explore the region’s past and present, a story that embraces a fusion of cultures and has shaped a set of regional identities which vary from island to island, giving each nation its own distinctive character.

The War Memorial in Basseterre remembering those men of St Kitts & Nevis who lost their lives in the First World War, 1914-1918 © Tim Smith

I’ve also asked people in Leeds how this multicultural heritage – African, European, Asian and Amerindian – is reflected by Caribbean festivals, music and masquerade, and how Caribbean carnival has become an important part of the cultural calendar across Britain. These interviews are featured in a film illustrated with my father’s photos of the Trinidad Carnival in 1967 (the same year that Leeds West Indian Carnival began) and my own pictures of carnivals across the Caribbean and Yorkshire.

The Renegades Steel Orchestra, a steel pan band, on the road in Port of Spain at the 1967 Trinidad Carnival © Tim Smith

It should also be remembered that the presence of black people in Britain stretches back many centuries. This history, and Leeds’ historical connections with the Caribbean, will be explored using material drawn from the collections of Leeds Central Library, curated by the Chapeltown-based arts project Heritage Corner.

A group of girls eating candyfloss making their way to the Junior Calypso Competition in Newtown, Dominica © Tim Smith

In many ways it’s a nonsense to attempt to cover such a large and varied area in a single exhibition, but whilst providing glimpses of different stories it also aims to be the catalyst for much more. Producing it has brought back many memories for me. I hope it does the same for others who once lived in the Caribbean, and inspires people to further explore the region’s history and its links with Britain, perhaps by investigating their own family stories. I also hope that many visitors to Island to Island will discover something new about the Caribbean, and some may be tempted to (re)visit an endlessly fascinating and diverse part of the world which offers so much more than the images and ideas offered up by the tourist industry.

A make-up workshop in the Hope Botanic Gardens, Kingston, Jamaica © Tim Smith

Island to Island

27 June 2018–27 July 2018

Room 700

Leeds Central Library

Municipal Buildings, Calverly St

Leeds, West Yorkshire LS1 3AB

Click here for more information

The exhibition is available for tour to other venues. Please contact: timsmithphotos@btinternet.com

Text and images © Tim Smith

13 April, 2018

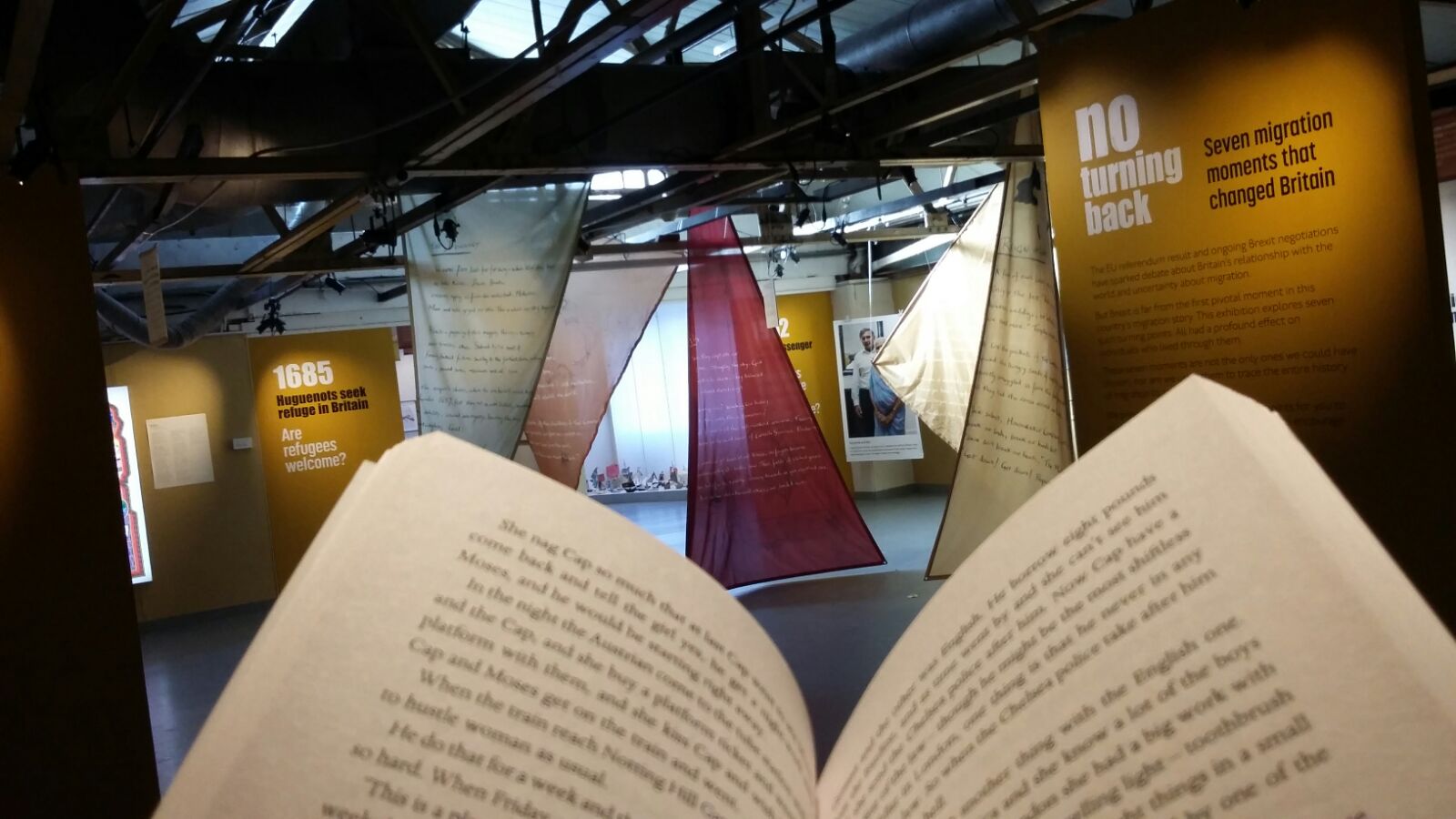

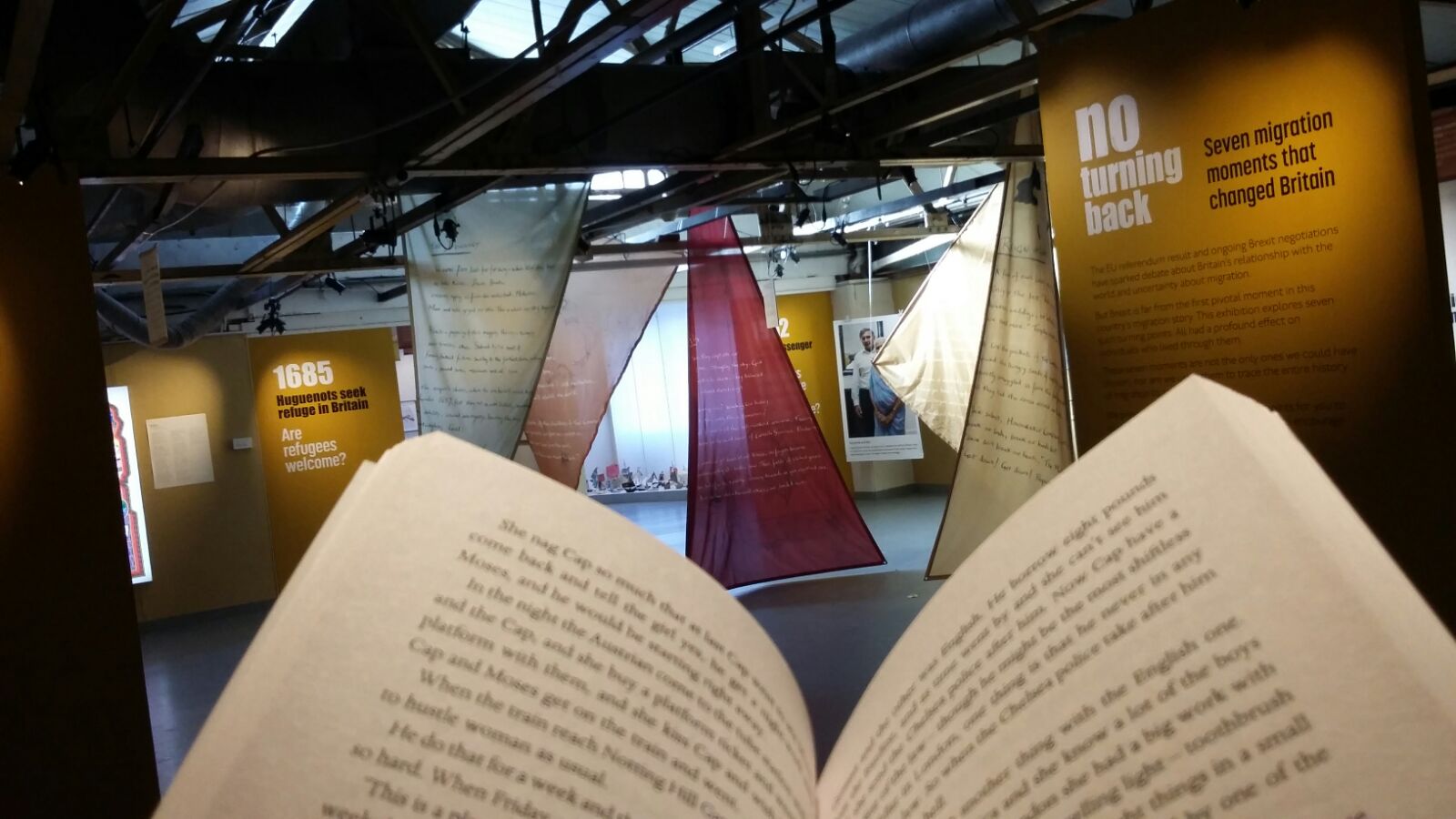

The Migration Museum Book Club aims to bring together those who have stories to tell and those who have read good stories.

Devised and run by our volunteers and based around a monthly theme, attendees are invited to bring a book, poem, article or a piece of their own writing to share and discuss with the group. Themes will be announced in advance of each meeting and will revolve around the subjects explored by the museum and its exhibitions, primarily focusing on migration, identity, and travel.

As the group develops, we hope to explore past, present, and future ideas through the lens of migration and grow the book club into a regular community, where people can share or just listen.

Our book club is open to all and there’s no need to register in advance – just turn up on the day.

Migration Museum Book Club dates:

Sunday 8 April 2018, 2.30pm

Sunday 20 May 2018, 2.30pm

Sunday 17 June 2018, 2.30pm

Sunday 15 July 2018, 2.30pm

Image © Tabitha Deadman

15 June, 2018

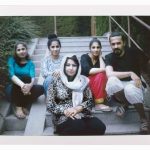

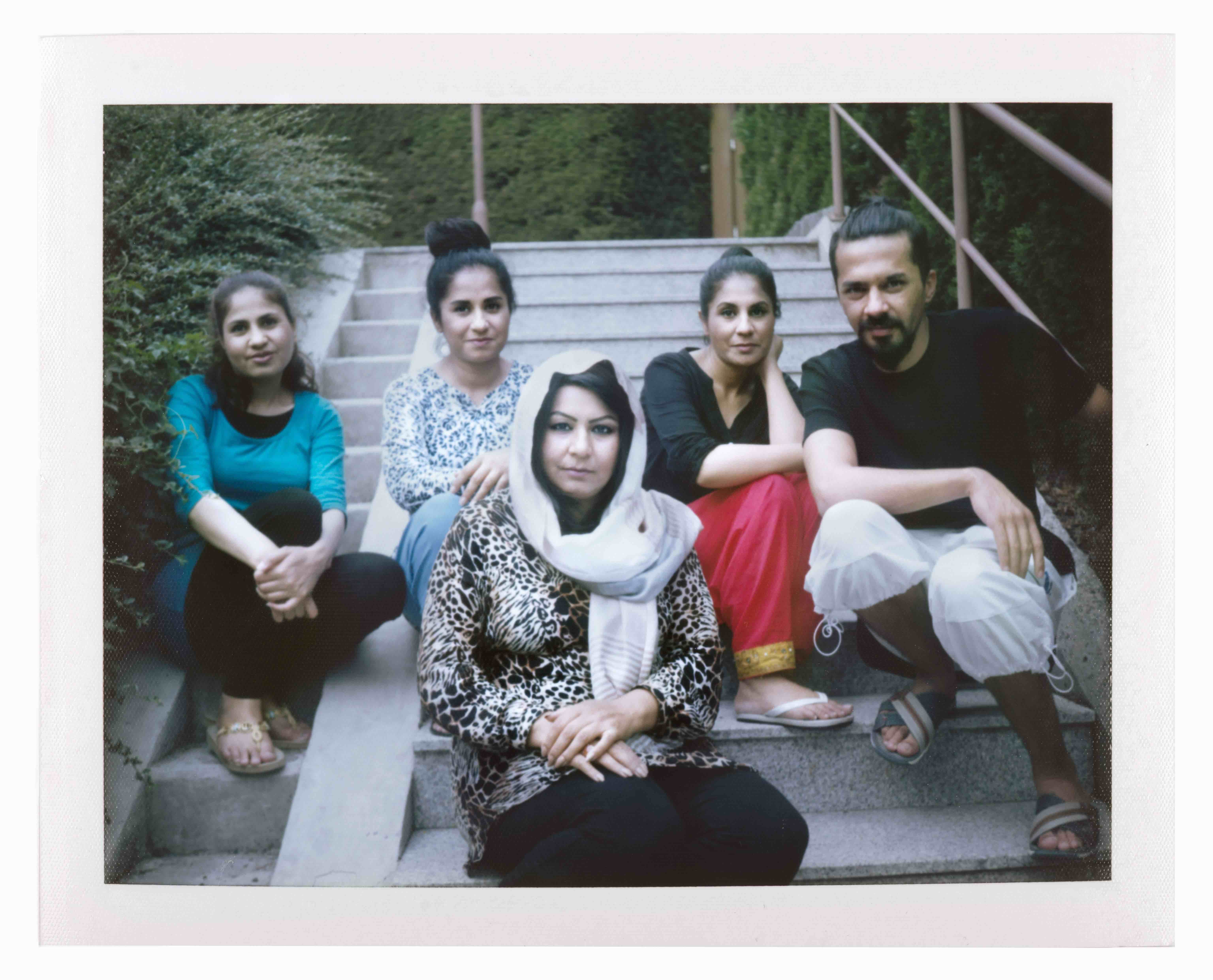

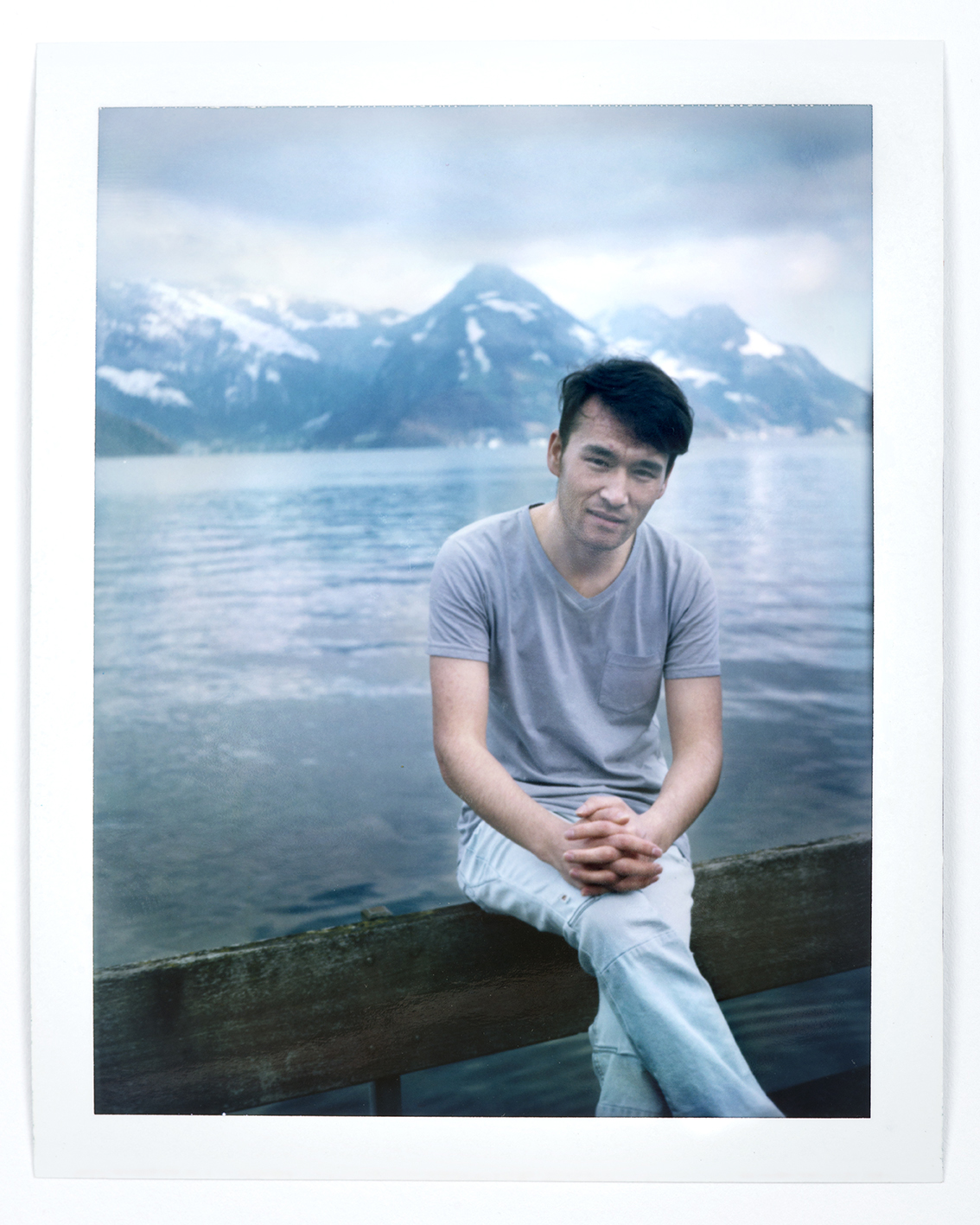

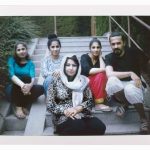

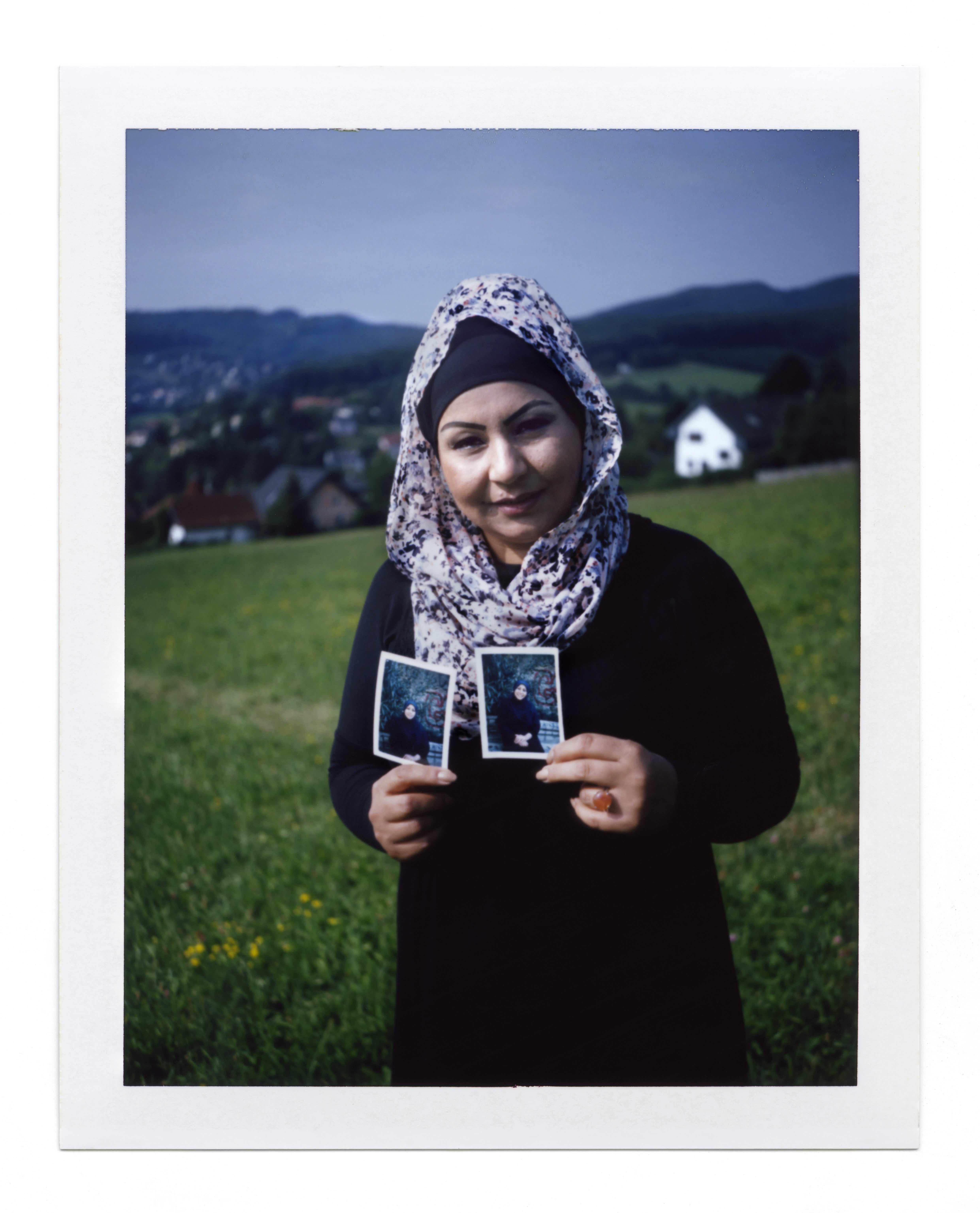

Fahima and family in Austria, part of Giovanna Del Sarto’s A Polaroid for a Refugee project © Giovanna Del Sarto

A guest blog by Giovanna Del Sarto, creator of A Polaroid for a Refugee, a photographic project depicting points of transition in the lives of individual refugees. As part of our activities for Refugee Week 2018, we are displaying a selection of images from A Polaroid for a Refugee at the Migration Museum at The Workshop until Sunday 1 July 2018. Giovanna will be speaking at our Refugee Week Late Opening on Thursday 21 June.

In 2015, after months spent reading newspapers, watching television reports and listening to different opinions about the refugee crisis in Europe, I felt the urge to go and witness.

My aim was also to volunteer, to be able to understand and be close to the people involved. Since October 2015, I have visited various locations including Preševo, Belgrade, (Serbia); Lesvos Island, Athens, Idomeni, where the humanitarian need was most tangible; and Chios, an island located just a few kilometres from the Turkish coast (Greece).

On all of these occasions, I had my Polaroid Land Camera with me – and it was during my first trip that the A Polaroid for a Refugee project was born.

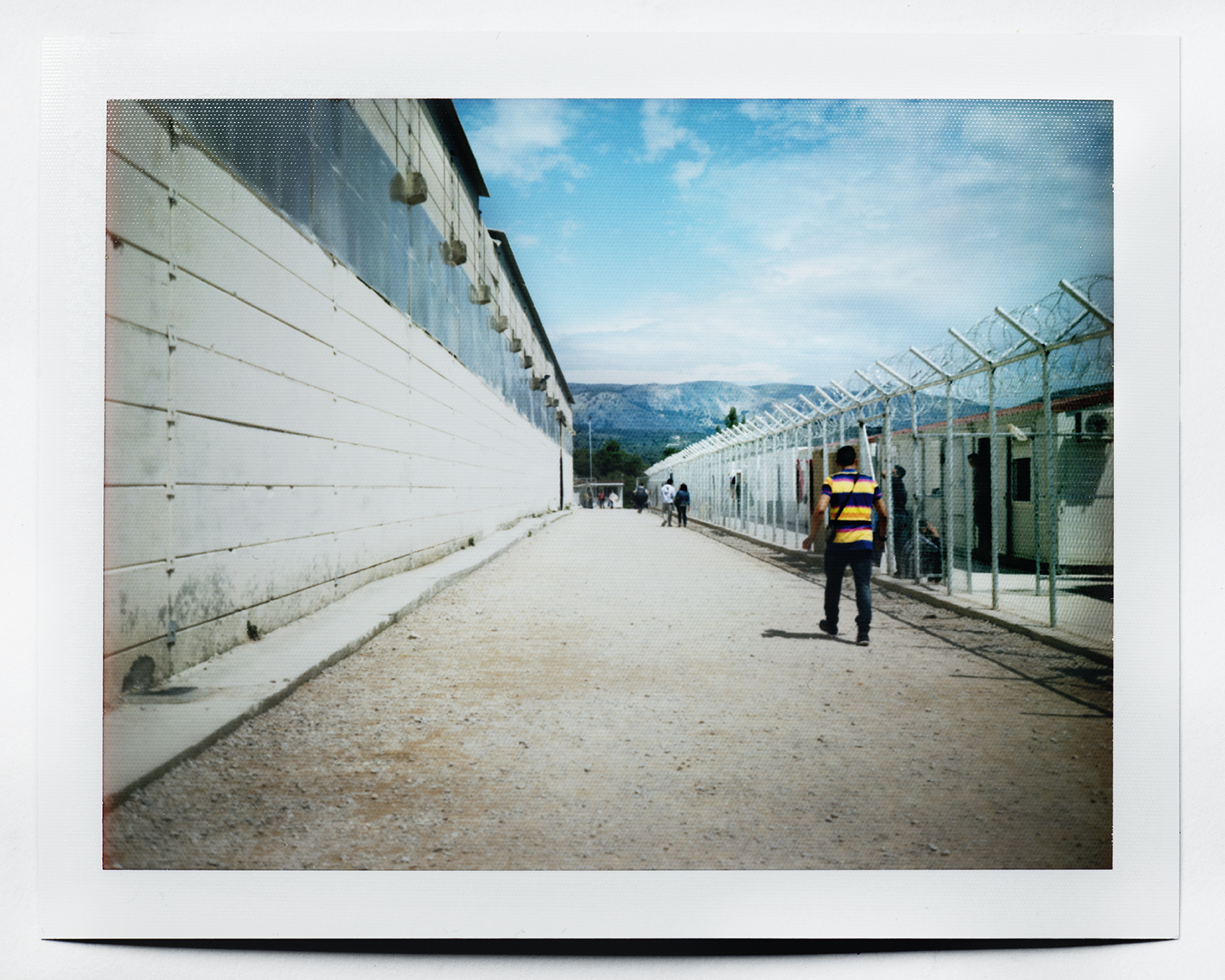

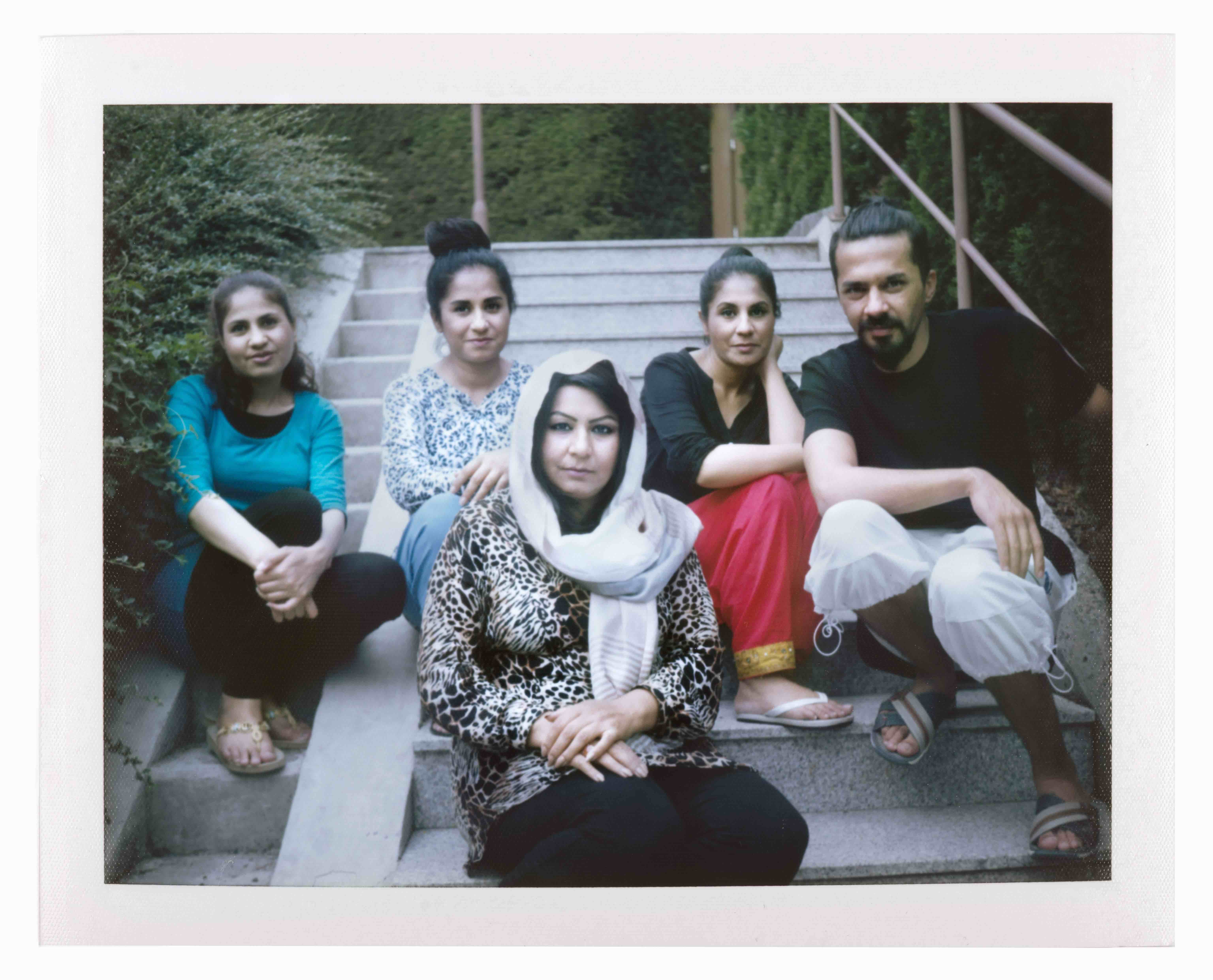

Chios Island, Greece, 2016, part of Giovanna Del Sarto’s A Polaroid for a Refugee project © Giovanna Del Sarto

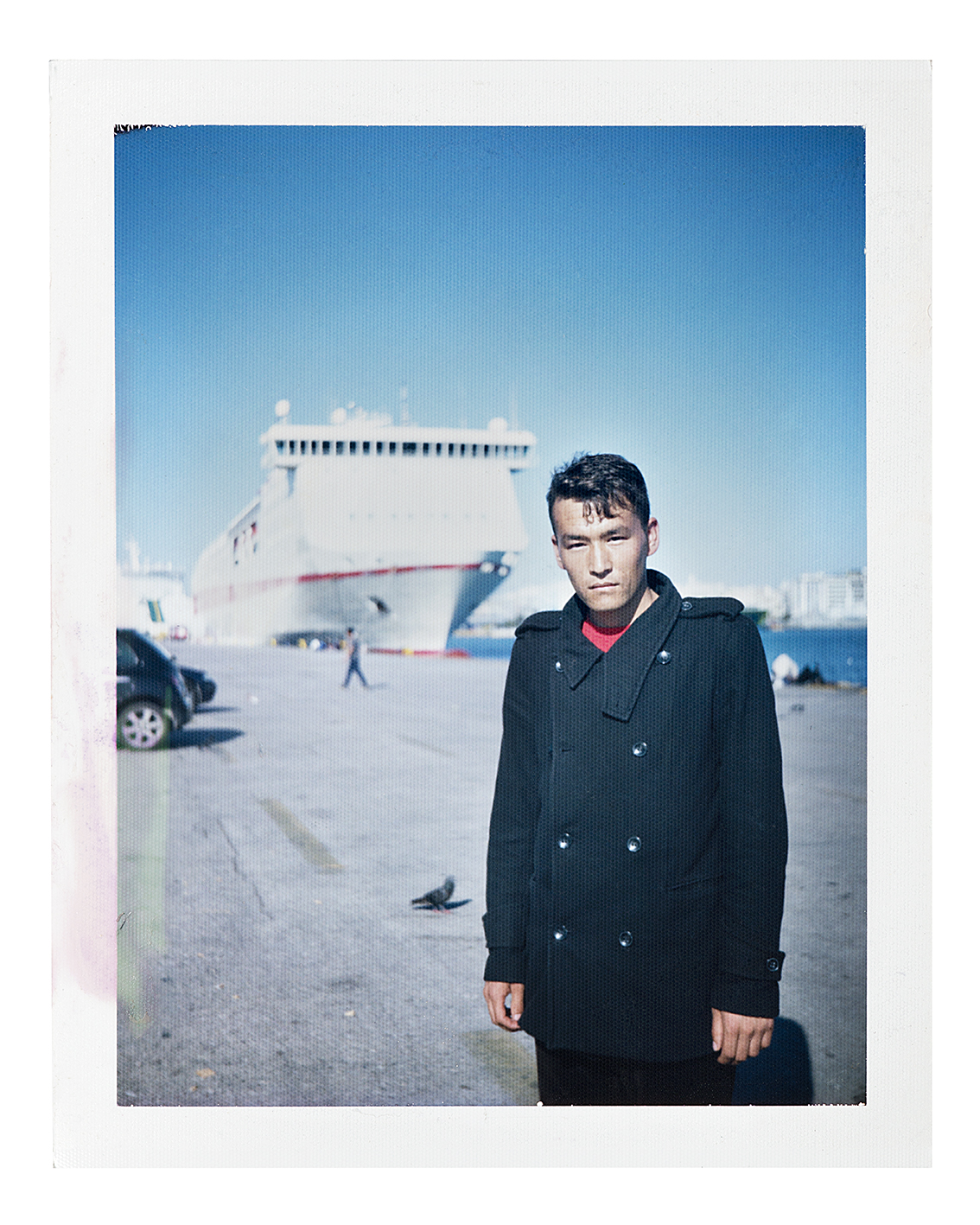

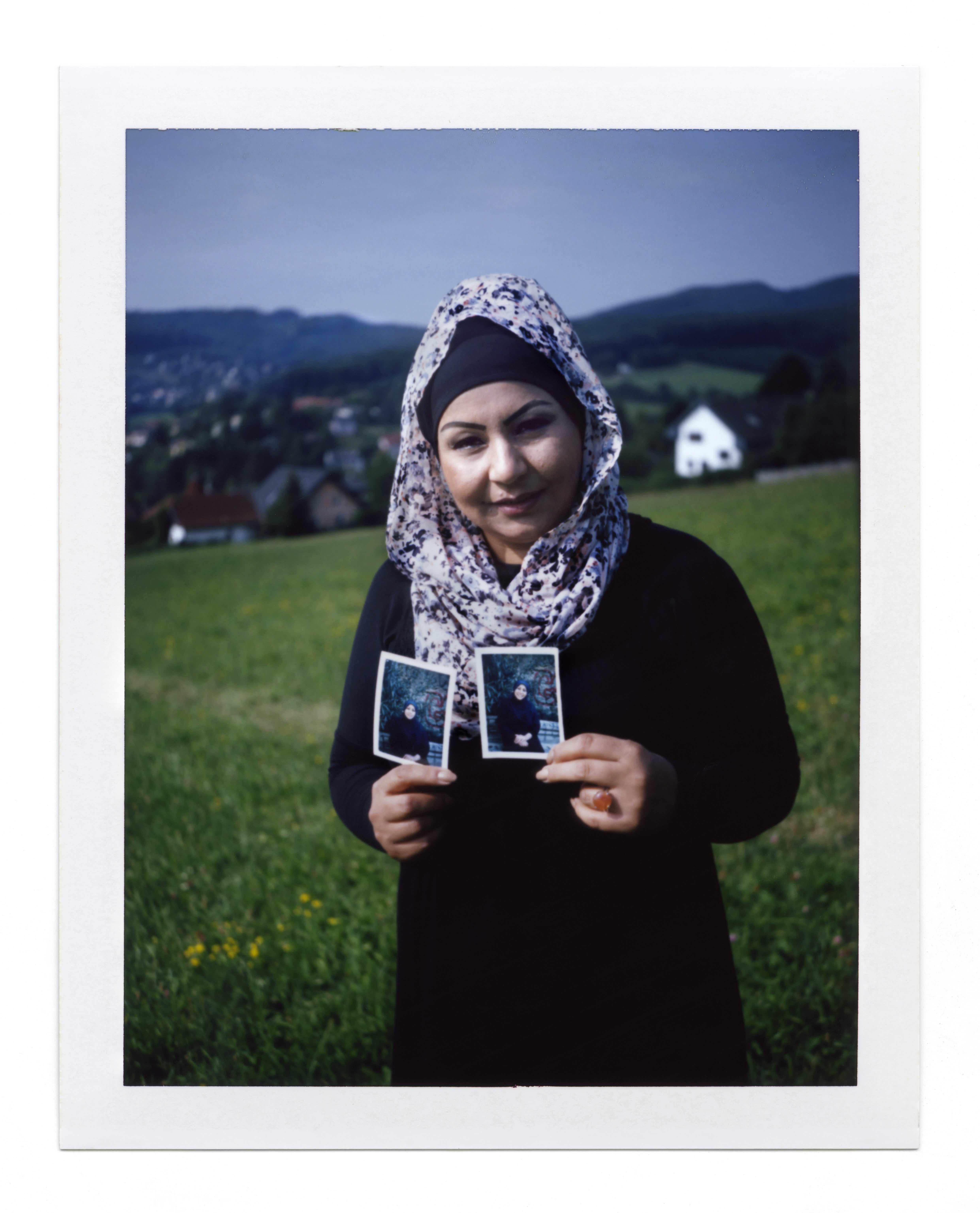

It is a project based on the concept of giving – giving something back to the refugees, a moment of their life and journey captured forever. The Polaroids reflect the inner strength and dignity maintained by refugees during their long and harrowing journeys. For every Polaroid I take, I give one to the refugee as a reminder of the moment. On the back of the Polaroid is a simple statement: ‘Wherever your destination may be – tell me when you feel you have reached a safe place.’ This is a message of hope, which, sadly, for some may never be fulfilled.

Everyone I photographed has a Polaroid now. I love the idea that they will look at those pictures one day in the future. The portraits I took are very similar to family portraits, conveying a relaxed and carefree attitude that only scratches the surface of the refugees’ lives. Yet the value for the refugee is to have this moment of escape from the horrors of their daily lives and to carry a reminder of it with them on their onward journeys.

Everyone wanted their photograph taken, but for many different reasons. The young men loved to pose; the mothers wanted a picture to show their children when they’re older; and the kids just saw it as a bit of fun.

And for us who look at these images? We see a different side to the refugee crisis from the one we’re usually offered. We see these people just as people, not as victims or heroes, not as refugees to pity or as migrants to fear. They emerge as humans – resilient, thoughtful, joyful individuals.

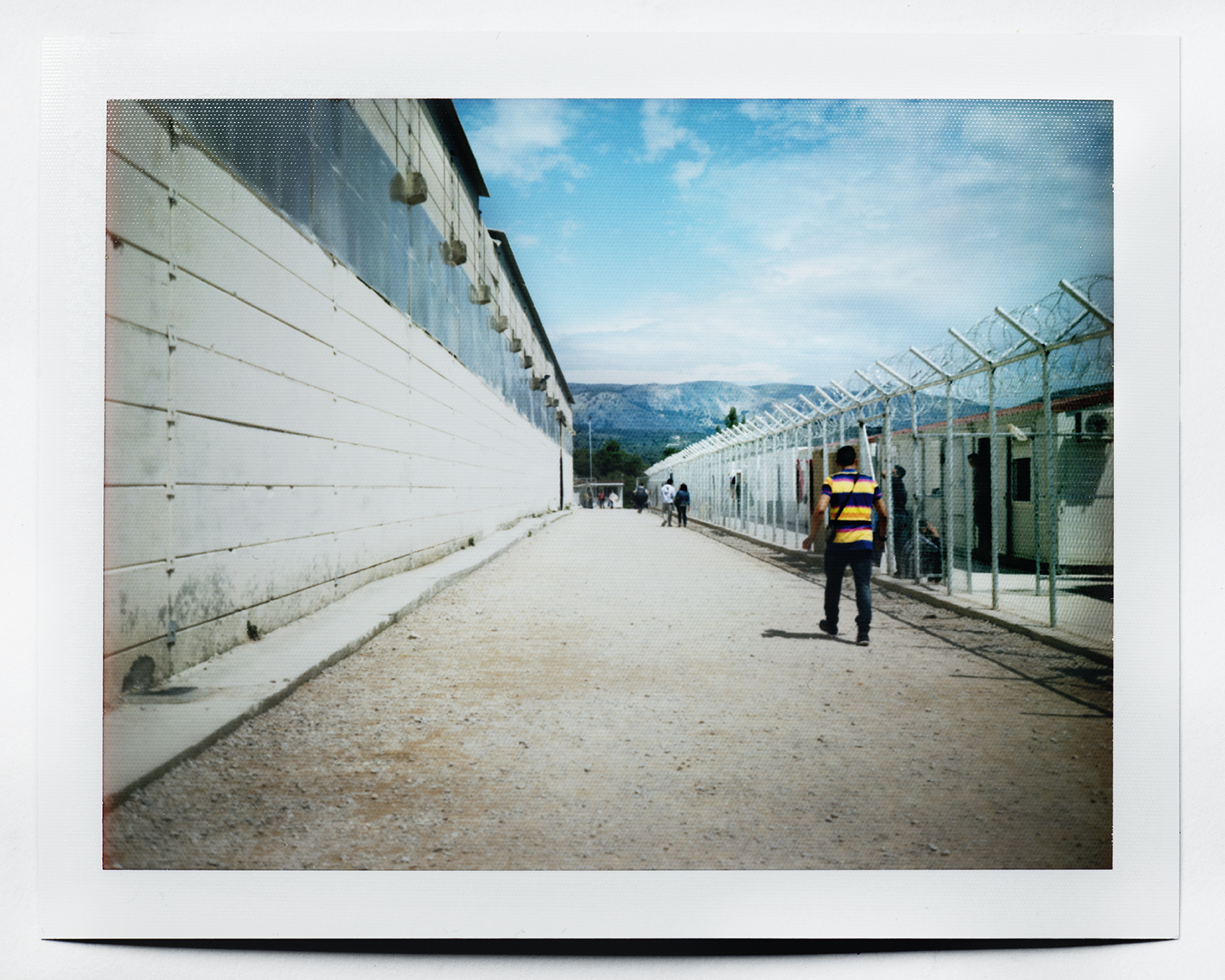

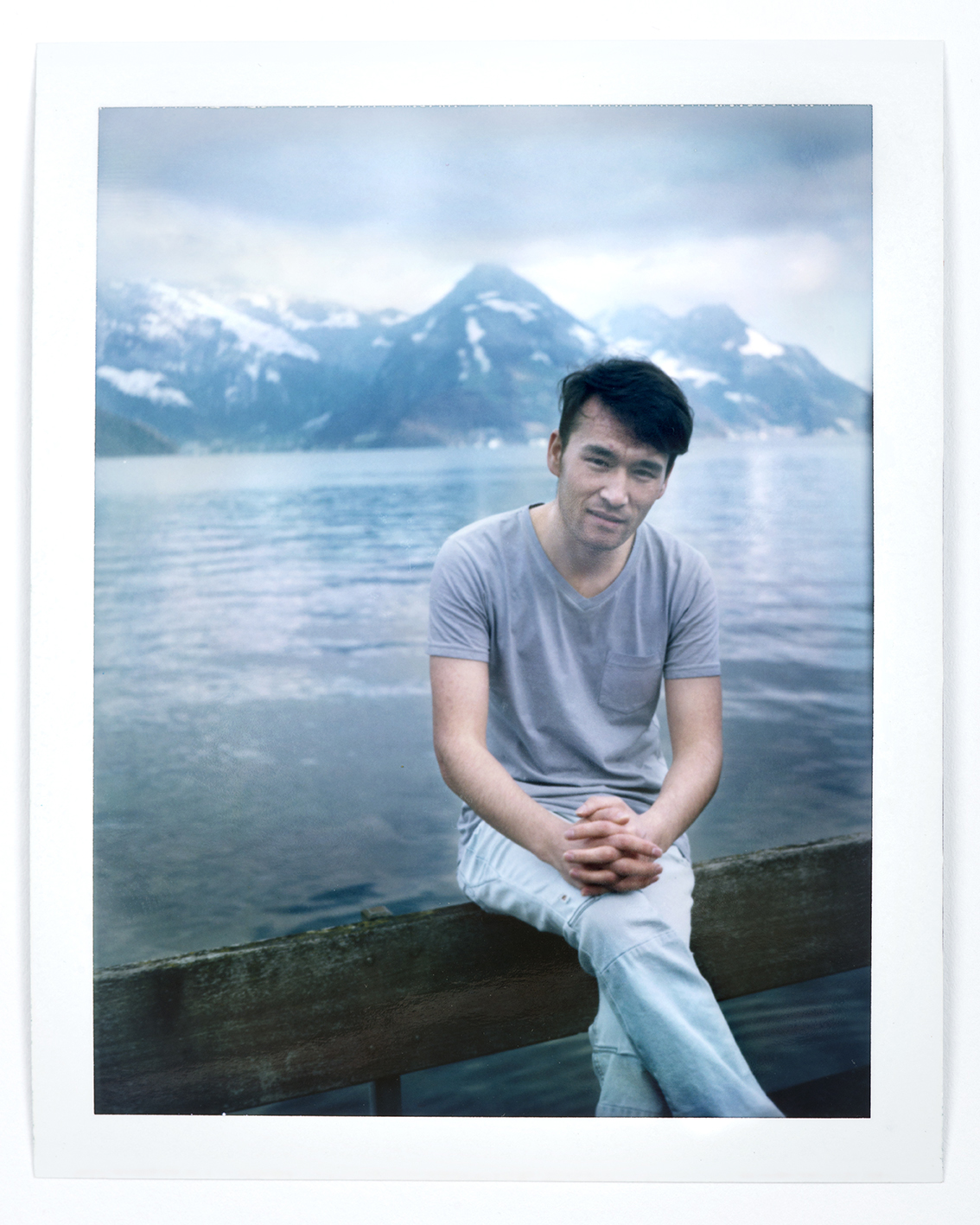

Mahbub in Athens, Greece, 2016

Since August 2017, I have been visiting people who have kept in touch with me and are building new lives in Europe. Some, such as Fahima, still have the original Polaroid, enabling us to reunite the two Polaroids in the place that they have chosen to rebuild their lives. Others, such as Rohina, had their Polaroids confiscated along the way but kept hold of my contact details and kept in touch.

I find this second stage of my project both fascinating and challenging, encountering situations that I might not have had if I had only focused the project on the Balkan route or if I had focused only on European countries that are considered ‘the destination’.

Fahima in Austria, part of Giovanna Del Sarto’s A Polaroid for a Refugee project © Giovanna Del Sarto

There is sometimes a perception that, once people reach their ‘destination’, everything will be magically healed. I met people along the way who didn’t have any money, food or means to carry on their journeys, yet somehow they managed to ‘make it’. At what cost, though? Some of the people I have revisited are struggling to come to terms with the memories and legacy of their journeys, and their new lives and circumstances.

Witnessing both situations has led me to realise how far away I am from truly understanding the experiences that these people have gone through.

Mahbub, Switzerland, 2017, part of Giovanna Del Sarto’s A Polaroid for a Refugee project © Giovanna Del Sarto

A selection of images from A Polaroid for a Refugee will be displayed in the stairwell and entrance corridor to the Migration Museum at The Workshop from Thursday 7 June until Sunday 1 July. Opening hours and visitor information.

Giovanna will be speaking about her project as part of our Refugee Week late opening on Thursday 21 June.

For more information on A Polaroid for a Refugee, please visit apfar.org or the project’s Facebook page.