At last, a larger slice of the cake

Martin Spafford, who sits on the Migration Museum Project’s education committee, writes here about developments to public examination at GCSE which, for the first time, enshrine migration education on the school curriculum. Emily Miller, the Migration Museum Project’s education manager, is working with Martin to promote migration education in schools.

Migration and the new GCSE curriculum in England

At a meeting about curriculum change in 2012, Nura Hassan, a 16-year-old East London school student, had this to say about school history:

‘If history is a cake, the government is cutting a small slice and forcefeeding it to us, pretending it’s the whole cake.’

Nura was referring to the fact that the rich diversity of the peoples of these islands was all but absent from what is taught in schools. Since then, two of the three English exam boards – OCR and AQA – have attempted to address the issue by making changes to their courses. As a result, 14–16 year olds in state and private schools across England – from rural Gloucestershire to urban West Yorkshire, from Southall to Norfolk, from Milton Keynes to Maldon – are studying the long history of migration to and from Britain for their GCSE exams. (For an account of the three available courses, see the text box at the end of this blog post.)

Government changes in the content of the history exam mean that all students must now study a theme, examining it across an extended period of time from the early Middle Ages to the present; schools select one theme from three offered them by the exam boards, and with three out of the four courses available migration is now one of those options. A head of history in West Yorkshire has said he has never been as excited about teaching as he was starting this topic, which allows his students of diverse heritage to see their place in our history. A Brent teacher said the lesson she designed to open the unit was met with greater enthusiasm by her students than any she had ever taught. A Midlands teacher says that the key concepts in the course – reasons for migrating, experiences, impact of migration, and the extent to which migrants have been accepted or rejected – are so close to his students’ own lived experience that they understand them easily when handling them as historians.

One of Hodder Education’s publications for the new GCSE syllabus; Martin Spafford, this blog’s writer, is a co-author.

A black soldier is shown with a rifle on the left of this relief panel showing Nelson’s death, from the base of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square.

New resources have been published, which some schools are using to rethink and change the way in which they teach younger pupils. In an East London school a new approach to key stage 3 for 11–14 year olds ensures that the many experiences of our diverse population are fully reflected in what is taught about every period in our history. A project run jointly by an Essex secondary school and 14 feeder primary schools resulted in years 5, 6, 7 and 8 of the schools working together to create a migration museum. Islington Council’s ‘All world history, all the year round’ programme, a move forward from Black History Month, is becoming embedded in some primary and secondary schools, spearheaded by the community organisation Every Voice.

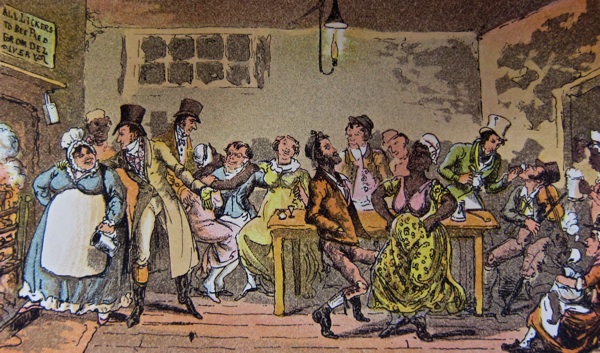

‘The Lowest Life in London’ – a cartoon by George Cruickshank, 1820.

Children studying Roman Britain can therefore learn that most of the ‘Romans’ who came (soldiers and civilians) were from Northern Africa, Western Asia, Eastern and South-Western Europe – and that many settled. Students can discover how the economies of medieval and early modern England were transformed by the skills, influence and investment of Jewish moneylenders, Flemish weavers, German merchants, Lombard bankers and Huguenot entrepreneurs. By looking at the free lives of Africans in Tudor England we can have a fresh understanding of how racial attitudes were later shaped – in devastating ways – by enslavement and empire. The industrial age can be seen through the lives of migrants from Ireland and Italy, as well as those from all parts of Britain, who constructed and worked the factories, roads and railways. Without Asian merchant seamen, not only the trade routes of the British Empire but also the Atlantic convoys in both world wars would have been impossible. And through the memories of parents and grandparents students can see how migration since 1945 has played a huge role in our economic, political and cultural life.

A representation of John Blanke, the trumpeter at the court of King Henry VIII. © Stuart M.

These are early days: schools choosing the Migration options are a minority, and projects with earlier years are just beginning. But we live in a climate of heated and often poorly informed debate, so it is increasingly important to equip children with knowledge that is based on evidence and research. Against that background, the acceptance of migration as a valid subject for school examination, and the availability of new resources that tell so many stories previously untold in schools, cannot have been more timely – even if both come, unfortunately, too late for Nura.

The courses on offer for teaching migration at GCSE

• Migration to Britain by Adi, Lyndon, Sherwood and Spafford

• Migrants to Britain by Lyndon and Spafford

• Migration, Empires and the People by Mohamud and Whitburn

A comprehensive resource and learning pack on Butetown, Cardiff can also be accessed and freely downloaded as a PDF. And the accompanying Our Migration Story website created by the Runnymede Trust is also free to access is.

Martin Spafford co-wrote the Hodder textbooks for the OCR migration courses and is a member of MMP’s education committee. Now retired, after nearly 40 years’ teaching (latterly in East London), he is now a volunteer trainer with www.journeytojustice.org.uk and a facilitator on a leadership project in West London schools run by Facing History and Ourselves. He enjoys working with young people around the meeting places of education, history, social justice, human rights and community action for change. At the moment he is preparing a schools pack on the migration history of South Tyneside.

Leave a Reply