River deep, mountain high – two weeks in April 1968

Ike and Tina Turner, probably most famous for the song “River Deep, Mountain High”, but not really the main subject of this blog.

The title is a reference to the song made famous by Ike and Tina Turner in 1966, lavishly and operatically (some might say bombastically) produced by Phil Spector. Fortunately for this blog, Eric Burdon and the Animals (themselves not averse to musical pyrotechnics) reprised the song in 1968, the year that is the focus of this blog – or rather two weeks within that year.

First, the river

The ‘river’ bit comes with the 50th anniversary on 20 April of Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. His speech can be heard in its entirety in Amol Rajan’s Radio 4 Archive on Four – ‘50 Years on: Rivers of Blood’. Because there is no full recording of the original speech – only those snippets that are regularly replayed to remind people of its content – the speech is delivered on the programme by Ian McDiarmid in an uncannily accurate resemblance to the man himself. Bizarrely, the ‘public’ parts of the speech – those that are regularly replayed – turn out not necessarily to be the most incendiary.

Much better people have written elsewhere about the speech itself and its repercussions. Though they were writing on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of his speech, both Oliver Kamm (in his brilliant skewering of the man and his myth) and Sarfraz Manzoor (writing from a more personal perspective, but also trying to track down the people referred to in Powell’s speech) are essential reading. I’m happy to leave to those others – and to the many writing at the time of its 50th anniversary – the speech and its lingering toxicity.

Enoch Powell, a politician who didn’t always give the impression that he was happy with the way things were.

But there are two other aspects of the speech that struck me as I was listening to Amol Rajan’s programme and reflecting on the commemorations.

The first is that, although it is universally known now as the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, Powell never in fact uses this phrase in his speech. What he does say is: ‘like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood”’ (incidentally, the ‘I seem to’, a phrasing he is fond of, seems to me an early example of humblebragging). An interesting linguistic inflation has taken place between ‘the River Tiber … much blood’ – where there is a single river, and the dominant constituent element continues to be water – and ‘rivers of blood’, where the plurality hints at a multiple, generalised tragedy, with blood the sole element.

Nobody seems to know when ‘River … blood’ became ‘rivers of blood’ and who was responsible for the coinage, but it becomes part of that family of phrases that are misrepresentations of the original (‘Play it again, Sam’ is another case in point, as are ‘It’s the economy, stupid’ and ‘A week is a long time in politics’) but which become the phrase that identifies the item in the public imagination. In their own way these are examples of fake news, only this time genuinely fake news, not the fake fake news routinely mocked by certain heads of state in an attempt to undermine verifiable facts and evidence.

The River Tiber – evidence of ‘much blood’ foaming about not immediately apparent.

Still the river, this time with swans in it

Our trustee Robert Winder (author of Bloody Foreigners and The Last Wolf) talked about the power of the media to create alternative truths in his inspiring Penny lecture on ‘Why do we fear migration?’ at Morley College, London, on Wednesday 18 April. He used as one example the story of ‘Swan bake’, a piece that had appeared in the Sun on 4 July 2003, with the subheading: ‘Asylum seekers steal the Queen’s birds for barbecues’. The story went on to describe east European poachers ‘luring the protected royal birds into baited traps’ and concluded that ‘the discovery last weekend confirmed fears that immigrants are regularly scoffing the Queen’s birds’.

Nick Medic, a Serbian journalist who had sought asylum in Britain following the collapse of former Yugoslavia, thought there was something fishy about this story and decided to investigate its key sources: a representative of the Swan Sanctuary and the Metropolitan Police. What he discovered was that nothing in the story reflected anything these sources had actually said; the closest link was the Swan Sanctuary’s rep’s second- or third-hand report that ‘a member of the public had phoned him some time previously and claimed that he could see someone pushing a swan in a shopping trolley’.

A shopping trolley containing a non-existent swan.

Following Nick’s submission to the Press Complaints Commission (PCC), the Sun issued a ‘clarification’ in which the paper acknowledged that ‘nobody had been arrested in relation to these offences’. Though the PCC agreed that the Sun had presented as fact what was actually conjecture, the Commission felt the Sun’s clarification represented ‘sufficient remedial action’.

The original story had been published on the paper’s front page; the clarification was published on page 41.

But punchy headlines are gold dust to reporters, and the Sun wasn’t going to use ‘Swan bake’ just the once. So, some eight years later, the same headline was trotted out on 4 February 2011, with the bold first paragraph: ‘POACHERS have been accused of slaughtering 14 swans and cooking them on campfires at a popular beauty spot.’ This time the ‘fact’ that the alleged poachers may have been East European was held back until the sixth sentence.

And now the mountain

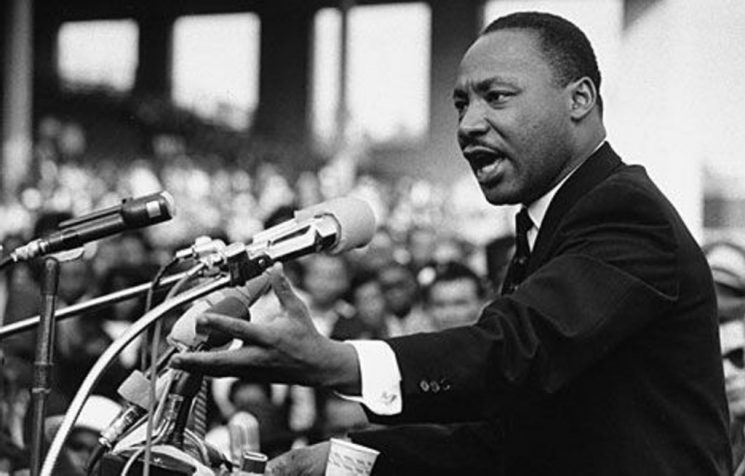

So much for ‘river deep’; what about ‘mountain high’? Well, Amol Rajan’s Radio 4 programme on Enoch Powell reminded me that Powell’s speech was delivered just two weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King, on 4 April 1968, one of those not-precisely coincidences that, from this perspective, makes the fact that Powell chose to deliver the speech at all certainly stranger, if not actually more provocative.

In almost all respects, of course, these two men have nothing in common, but King and Powell were both considered, certainly by their supporters, to be the pre-eminent orators of their time – though their opponents were more likely to consider them dangerous firebrands, with the rabble-rousing abilities of all populist extremists. Both were capable of oratorical flights of fancy, often couched in biblical language. Both were held in high regard for the power of their intellect (Powell in particular, though Matthew Parris, on Amol Rajan’s programme, wonderfully dismisses him as ‘a stupid person’s idea of an intelligent person’) and for their commitment to the democratic principle. That fortnight in April ’68 also saw the end of both men’s careers – King’s literally and murderously, Powell’s by virtue of being banished to the political wilderness. That’s probably where the similarities end. In the 50 years following their death and disgrace, respectively, King’s star has continued to rise to Mandela-like proportions, and his moral righteousness and political courage are acknowledged now even by his opponents. By contrast, few people see Powell for the Old Testament prophet he was often presented as at the time, and his legacy lies almost entirely in the explicitly right-wing and racist/xenophobic parties that have formed in his wake and which hail him as an inspiration.

Martin Luther King (1929–68). What can you say? One of the greatest Americans who ever lived – one of the greatest people, full stop.

And whereas Powell talked about a river of blood, King – in his final speech on 3 April 1968 – talked about a mountaintop from which he had been able to see the Promised Land for his people. Rivers foaming with much blood on the one hand, a mountaintop of hope on the other; venom and bile dressed up as an intellectual exercise in democratic accountability in one corner, raw passion and tremulous belief in the other. You’re bound to know King’s speech already: but, even if you have heard it countless times, listen again to its final four minutes. The way in which he strings out the word ‘seen’ in his phrase ‘I have seen the promised land’ across several syllables and almost two seconds will still bring a shiver down your spine.

I’d love to be able to say that Eric Burdon’s version of the song is better than Ike and Tina Turner’s – he’s long been a hero – but it’s not. But then neither of them is as soulful or as heart-rending as Martin Luther King’s final speech.

Leave a Reply