Doors onto lives

The portraits of Dharmendra Patel

It’s only about 10 metres’ walk from the door of the Heritage Gallery in the Old Royal Naval College at Greenwich to the lecture room at its far end but, in the spring of this year, for the time it took you to cross the floor you would have been unable to avoid the image of a man crouched on the ground beside a radiator in front of you. This is ‘Yasser’, Dharmendra Patel’s stunning photograph of a Sudanese man painfully and emotionally stranded between the country in which he has been granted asylum status and the country he is still scared he will be sent back to.

Yasser – Birmingham, 2010 © Dharmendra Patel. Dharmendra’s full caption to the photograph is given at the end of this blog.

In the Heritage Gallery, where photographs from our 100 Images of Migration were on display, ‘Yasser’ was huge: literally, in a print (courtesy of the University of Leicester School of Museum Studies) measuring 3.5 metres wide and just over 2 metres high; but also metaphorically, in the mesmeric power it had to draw people into the space. Visitors sheltering from the rain in Queen Anne Court would see the picture and find themselves drawn into the room to look at it more closely. It was always one of the photos that received the most mentions in visitors’ comments.

Pastor Reynolds – Birmingham, 2010 © Dharmendra Patel. Dharmendra’s full caption to the photograph is given at the end of this blog.

On the adjacent wall there was another portrait, less harrowing and smaller in scale, but quietly powerful nonetheless. This was ‘Pastor Reynolds’, another photograph by Dharmendra, this time of an old man sitting in a (clearly) favourite armchair, surrounded by the bric-à-brac of his life, and looking into the camera with a gently contented smile.

Not exactly polar opposites, ‘Pastor Reynolds’ and ‘Yasser’ nevertheless epitomised the range of experience 100 Images of Migration set out to convey. Each packs a huge punch; each comes across as entirely natural – a life captured in an image – even though its artifice is plain to see. These are posed photographs, but photographs of rare depth and clear engagement between photographer and subject.

Dharmendra Patel is waiting for me at the railway station of Sandwell & Dudley, but I walk straight past him, embarrassingly because I am looking for a woman: Dharmendra signs himself ‘Dee’ on his e-mails, in wry recognition of the difficulty people who are not of Indian origin have in pronouncing his name – and the only ‘Dee’s I have met previously have been female. Dharmendra takes the confusion with good grace (good grace is clearly something he was born with) and we joke about it as he drives us to the municipal office where we are going to talk – and about the Chelsea footballer Azpilicueta, who was called ‘Dave’ by fans and players because they found his name too difficult; and how many British Asians get called by their family names, which are considered easier to pronounce than their first names. The embarrassment passes – and it was all on my side in any case.

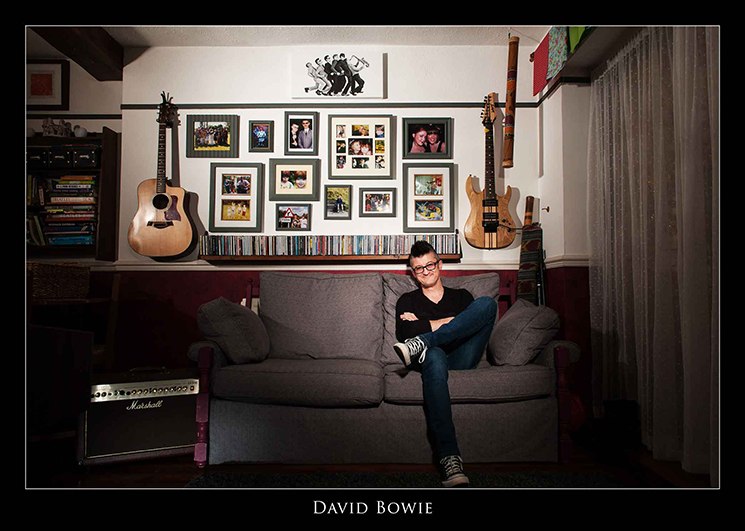

Spoz; the first of four ‘Couch Stories’ portraits featured here. Each person was asked who they would like to be sitting alongside them on the couch or sofa, and their answer is given in capitals at the base of the photograph. Spoz is a former laureate from Birmingham, who enjoys listening to and playing music. © Dharmendra Patel

Dharmendra describes himself as an environmental portrait photographer. It’s the Ronseal description of what he does, which is to photograph portraits of people in their own environment. Both ‘Yasser’ and ‘Pastor Reynolds’ are examples of this approach, though they were in fact part of an earlier project, Land of Hope and Glory, which you can see on Dharmendra’s website – and for which he has written an introduction that I urge you to read: in a few hundred words it says more about migration in this country than I have read in articles ten times its length. It says so much about the man, too: his easy grace, his self-deprecating character, his excitement at having stumbled on something that he recognises to be so powerful.

For Dharmendra did stumble upon photography. He had always enjoyed photography, and done it, but it is only recently that he has practised it professionally. Before 2010 he worked in the clothing industry, having graduated from De Montfort University with a degree in business management and marketing. The change came, first, in 2008, when he bought a digital camera, and two years later, in 2010, when he was one of 15 people from different artistic backgrounds accepted onto a professional development programme. For Dharmendra this led to Land of Hope and Glory, a project in which he was, as he puts it, heavily mentored by Vanley Burke, the great photographic chronicler of the black community in Birmingham and Handsworth.

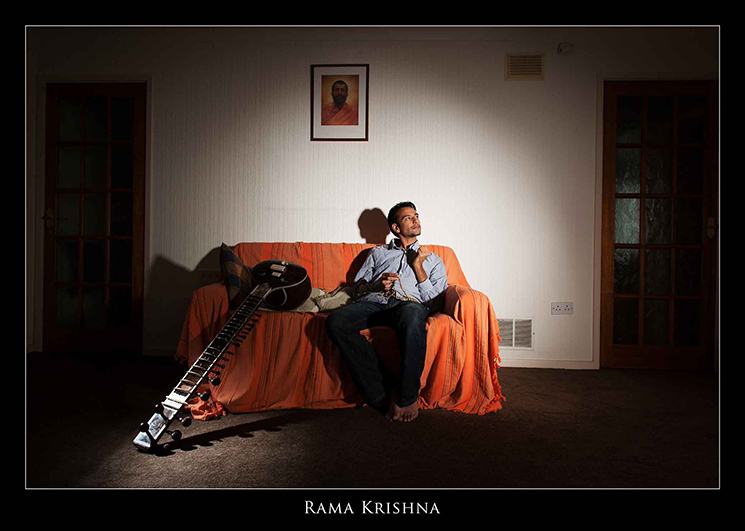

Rohit, a call-centre manager from Birmingham, is a sitar player and spoken-word poet. © Dharmendra Patel

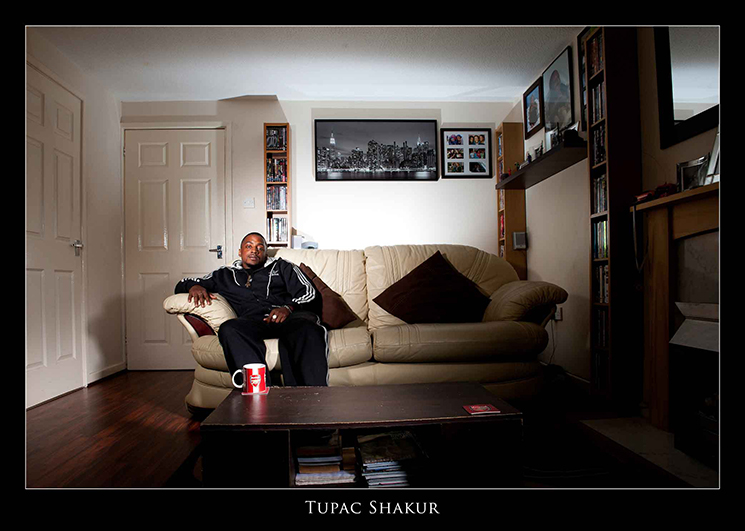

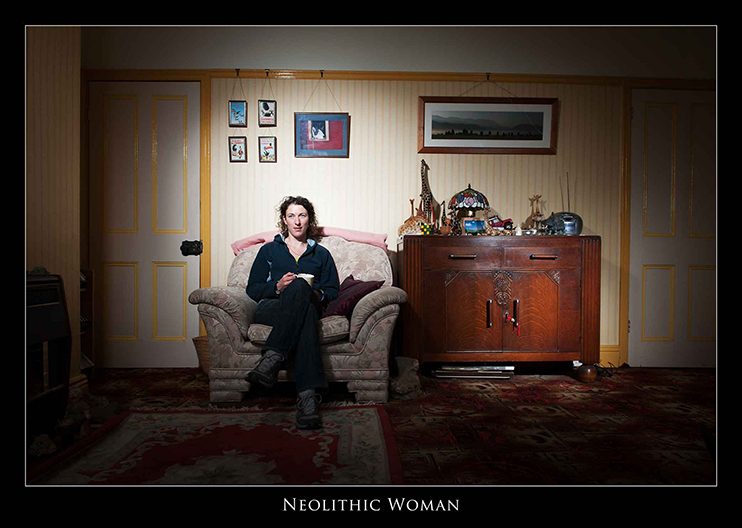

Professional since 2011, Dharmendra has honed his portraiture skills over the course of the years, tracking down the photographers of images he loves and asking for their secrets, especially their tips on lighting (two strobes and a hot-shoe flash, all off camera, for any technophile who might be reading this). More recent projects – especially his Couch Stories, the source of most of the other photographs on this blog – show how much he has refined his technique. He is meticulous about setting up his portraits but candid about the fact that many of his best photos have been taken when he’s pretending to set the lighting up and when the conversation has just reached a point where there is an obviously natural connection between photographer and subject. His photographs are joyful, even when they tell painful stories, because of the clear empathy he has for his subjects. Human warmth courses through the celluloid. And through what he says, whether it’s in print or in person. To go back to ‘Yasser’ and ‘Pastor Reynolds’, these are powerful photographs in their own right, but they are doubly so when they are viewed alongside the text that Dharmendra has written about them.

Fab, a videographer and actor based in Birmingham, starred in a play at the RSC in Stratford. © Dharmendra Patel

His parents (she from Kenya, he from India) moved to this country in the late 1960s, and he grew up and went to school in Leicester, in a predominantly white neighbourhood where he got used to the predictable, if off-target, taunts of ‘Here come the Pakis’ (as a quiet act of vengeance he relished his schoolmates’ inability to distinguish between people of Indian and Pakistani heritage). Dharmendra is aware that some people claim never to have experienced racism – but he did, and it was something that came between him and his father, who (in a way typical of a first-generation migrant) preferred not to hear the racial abuse that the two of them experienced on the street. When he walks down the street with his own daughter now, Dharmendra wonders how he would respond to similar taunting – but it’s clear to both of us that he wouldn’t allow it, more importantly that he wouldn’t allow his daughter to believe people should be able to get away with that kind of abuse.

Louise, one of Yorkshire’s first female dry stone wallers, enjoys hiking and wild camping; she also teaches chainsaw and tree-felling courses. © Dharmendra Patel

Born and bred in Britain, Dharmendra always identified as British, but it wasn’t until he visited his father in India, who had just had a heart attack on a visit to his home village, that he had a recognition of stark clarity that ‘This was where I am from’. Since then, he has thought more about his extended family, his father and mother’s backgrounds, and the country of their origin. We talk about how it is feasible to have multiple loyalties and identities, and I sense that this lies at the heart of many of Dharmendra’s photographs: talking to people about where they belong, where they feel most comfortable, where they’re at home. On one level it’s a small project he has taken on, an exercise in miniatures, but it’s one that he has transmuted into something grander, something magical.

And it’s not entirely magical, but I like the story of how he met his wife, who was living in Walsall at the time, where Dharmendra had moved in 2002. Near enough to be almost neighbours, they actually met in India, where the two of them were attending the grand opening of the recently refurbished village temple of which Dharmendra’s grandfather was the priest – it turns out that their fathers knew each other. It’s a doubly sweet coincidence because the meeting of course led to their wedding, and the one aspect of Dharmendra’s professional life that he finds the least stimulating is wedding photographs, the staple diet of many a photographer.

I’d worried, when booking train tickets to meet him, that I’d left far too long between trains and that I’d have to invent some other engagement to go to when conversation ran dry. I needn’t have: we talk so long that we lose the chance to have lunch and missing my train back also begins to look a real possibility. ‘It’s all to do with stories,’ Dharmendra says about his photographs. ‘The images are just a door opening onto a life.’ I think about the phrase on the train back to London, how close it is to our own strapline of ‘All Our Stories’ – and I understand again the power of ‘Yasser’ and ‘Pastor Reynolds’ to move people.

Dharmendra’s full captions to ‘Yasser’ and ‘Pastor Reynolds’

‘Yasser’ – Yasser was brought up in a rural district near Khartoum. Growing up was hard – “Human rights are like the lottery in Sudan: some get it, some don’t.”

He fled his country at the age of 28 after being imprisoned and tortured by the Sudanese State; leaving his mother and younger sister behind, he came to England. He had very little money and no contacts here. He was granted asylum in 2005. He loves the UK but, even though he has asylum status, he is scared to call on the authorities such as the police or the ambulance in case he is sent back to Sudan.

I decided to take the picture the way I did because it shows how he was feeling. It made me realise how much I was taking life for granted. I am the same age as this man, and his upbringing and mine were vastly different.

‘Pastor Reynolds’ – Pastor Reynolds was born in 1929 and came to England on 15 March 1960. It was difficult leaving his family and friends for a new land of opportunity and promises. Uncertainty got the better of him and he spent his last few moments in Jamaica contemplating what he was going to leave behind. This was the first time he had travelled out of his country. When he landed, the cold hit him and he spent the first few days battling homesickness.

Pastor Reynolds spent 20 years working on the railways of Birmingham and for a large engineering company before becoming a pastor.

The image was taken at the Pastor’s home in Birmingham. I decided to take the picture there because it was a reflection of his personality: relaxed and easy-going. He’s now retired and spends a lot of his time at the church and watching his children and grandchildren grow up.

Dharmendra Patel’s photographs are on display on his website: www.outroslide.co.uk His Twitter feed is @outroslide

Leave a Reply