Regrets? He’s had a few …

A profile of Charlie Phillips, photographer and contributor to 100 Images of Migration

Charlie Phillips had never planned to be a photographer. When, in the standard career interview towards the end of his time at school, the youth employment officer asked him what he wanted to be, Charlie answered ‘A naval architect’. Even now, his eyes fire up more when he’s talking about ships or the Middle Passage (‘my favourite passion’) than about almost anything, except maybe Britain’s renunciation of its maritime past – one of the derelictions of duty he can’t quite forgive his adoptive country for. And, in fact, his passions are many: don’t get him started about Captain Bligh and the role that breadfruit played in the mutiny on the Bounty, or about Captain (as he then was) Nelson, who met his wife, the daughter of a plantation owner, in his service in Antigua – or, rather, do, because he talks about both with the eye-glistening enthusiasm that he brings to the many subjects that fascinate him.

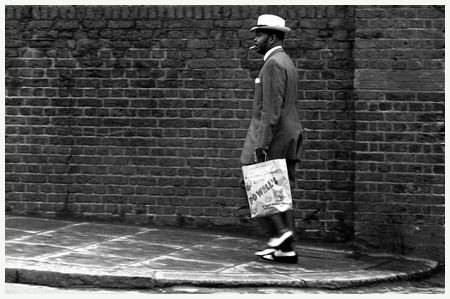

Man in zoot suit, Great Western Road, 1968. One of the sharp dressers of the period. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

But we’re here to talk about Charlie’s photographs, here being the Tabernacle in Notting Hill Gate, which Charlie has been visiting for a long time and where, seated outside in the bitter summer cold, he is warmly greeted by everyone going into and out of the building. His photographic career began by accident. A visiting GI left a Kodak Retina camera behind and Charlie instinctively took to it, photographing the people and places of Notting Hill, moving between 200 and 400 ASA black-and-white film and printing the results of his shoots in the family bathroom when his parents had gone to bed. Entirely self-taught, he continued to take photographs on and off for the next 30–40 years until the arrival of the digital camera put paid to his career (Charlie says that he ‘refused’ to make the move from analogue – stamping the act as the political statement he feels all our actions are). Sadly, all too few of his photographs have survived a life that started in Jamaica and which, from London, careened between Ireland, France, Italy, Switzerland, before pitching Charlie back in London.

Schoolgirls, Lancaster Road, 1970. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

London had never been the long-term plan, either at the start of his stay there or with his return 25-odd years later. Charlie had left his native Jamaica in 1956, sailing to Britain on the Reina del Pacifico (he has perfect recall for all the ships he has been on or seen). The idea was to stay in London for something like five years and then to go on somewhere else, most probably America, which is where other members of his family went. Instead, after the ill-fated interview with the youth employment officer had quashed Charlie’s dreams of naval architecture (the officer had suggested he should try the postal service, the RAF or London Transport instead), he spent three years in the merchant navy, working mostly in catering. He had always been interested in running away (he cites Norman Rockwell’s painting ‘The Runaway’ as a source of inspiration) and when he left the navy he did just that, travelling to Paris and becoming embroiled in the events of 1968 – ‘the start of my revolutionary, my bohemian years’ – before hitch-hiking further south to Italy, where he spent a further ten years.

The Reina del Pacifico, the ship on which Charlie arrived in England.

Charlie feels his career as a photographer really took off only when he left England and, with slight bitterness, lists a number of other black British artists who had to go abroad to make their name. In Italy he worked for commercial gain as a paperazzo, living in a commune but hob-nobbing with the artistic cool set of the time. That’s him in the notorious banquet scene in Federico Fellini’s Satyricon, in which a whole cow is split open to reveal cooked meats inside – the only part of the film, I’m delighted to tell him, that I remember in vivid detail; he knew and admired Giorgio de Chirico and was respected and valued by the artists he associated with: ‘They called me “the black Cartier-Bresson, compared me to Fox Talbot and stuff’. And it was in Italy that he had his first major exhibition, in Milan. After a second, this time in Switzerland, he followed his heart back to London, where he has been based ever since and where he now spends his time tending his rose garden, looking after his tomato plants and trying yet again (this is now his eighth attempt) to read War and Peace.

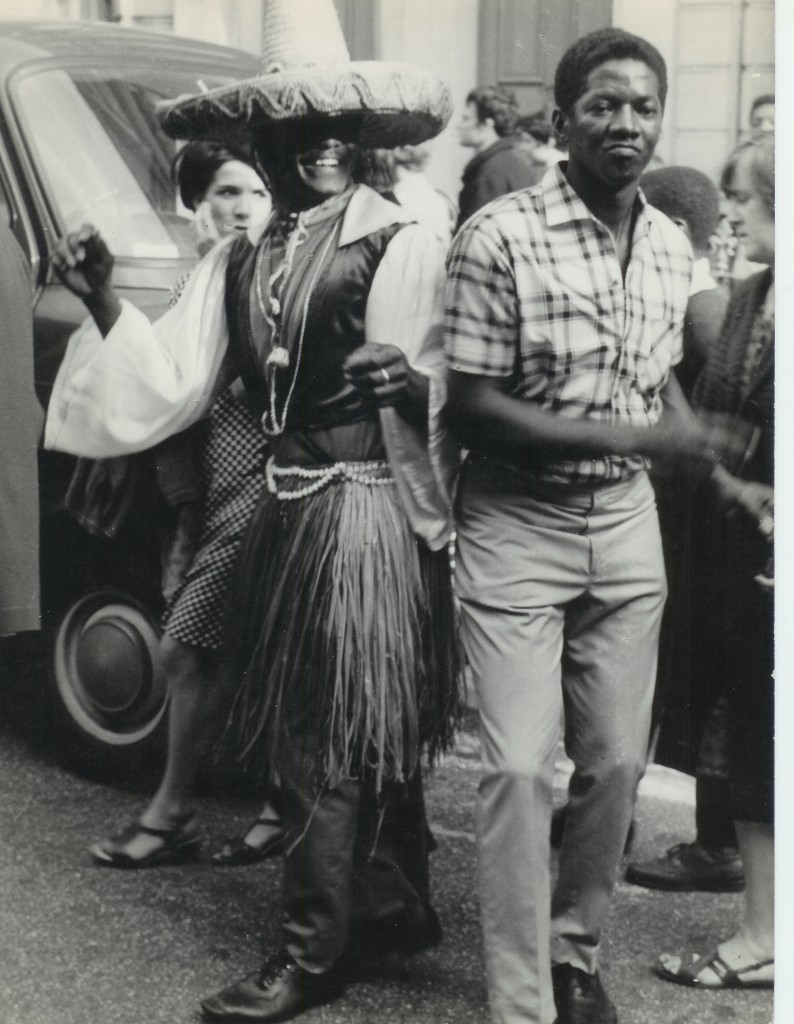

Ledbury Road, 1968. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

Too few of Charlie’s photographs have survived his European peregrinations: you sense that Charlie was often too interested in the present to concern himself with archiving his past achievements. All the photographs he took of Jimi Hendrix, for example, were lost in Charlie’s mid-period movement from squat to squat. Indeed, his recent exhibition, How Great Thou Art, a collection documenting 50 years of African Caribbean funerals in London, came about when two other photographic professionals Charlie knew took on the task of sifting through some of his old boxes in an attempt to help him de-clutter his life. The exhibition itself was then crowdfunded through Kickstarter.

Jennifer, Jamaica Independence Day, 1962. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

We will have to content ourselves, then, with the few remaining photographs that Charlie can lay his hands on. But these still have a tremulous power and an immediacy and presence that mock the intervening years. When schools and colleges visit our 100 Images of Migration exhibition, Charlie’s photos are always among those cited as the visitors’ favourites – many of the younger people are shocked at ‘Room to Let’ or captivated by ‘Notting Hill Couple’, aware about how powerful that image must have been at the time but conscious now of the open ease of the subjects’ pose, the classical simplicity of the composition.

Belatedly, Charlie is getting something of the recognition he deserves. The fact that this has arrived decades after he stopped taking photographs doesn’t seem cause for regret. In fact, don’t mention ‘regret’. Among the many things that Charlie still feels passionately angry about – the fact that the ‘Arts establishment’ has no interest in community artists, that ‘the bureaucrats have taken over the asylum’, that London feels, to him, culturally demoralised – is the banalisation of the Caribbean funerals that were the subject of his recent exhibition. ‘Do you know what the most frequently requested song is now, for the moment when the coffin goes into the grave?’ he asks indignantly. ‘When it used to be “How Great Thou Art”’ – and for a moment he goes off piste and intones the start to the hymn – ‘it’s now “My Way”. Can you believe?’

The funeral of Cassidy, a motor mechanic. Before his death Cassidy had asked not to have a hearse and so his coffin was taken to the cemetery on his employer’s Land Rover, in honour of his trade. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

It turns out that Charlie always fancied himself as a singer, too, even wanted to be an opera singer at one time. He’s off to the opera this evening, as it happens. Not the Royal Opera House, of course (he refuses to go to the fat-cat palace it has become), nor to the ENO (purist and revolutionary at the same time, he dislikes its failure to stick to the original librettos), but to Opera Holland Park, as ever supporting the local, the community. ‘Still the old revolutionary,’ he says – though his major concern, he tells me in the few minutes we have left, is the inability of grandchildren to communicate with their grandparents. He feels that somewhere between the late 1970s and the 1990s a cultural gap grew that hasn’t yet been filled, one which is full of stories still to be told.

Notting Hill Couple, 1967 – one of Charlie Phillips’s photos in the ‘100 Images of Migration’ exhibition that always attracts intense interest from visitors. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

He might be right. But his photographs have bridged that gap a long time ago, and continue to do so for every person who comes across them for the first time.

Leave a Reply