The price of emancipation

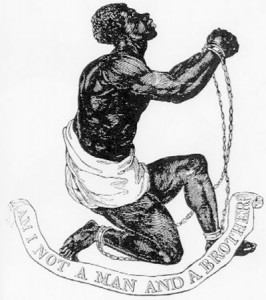

“Am I not a man and a brother?” The official medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society (1795)

Emily Miller, Education Officer at the Migration Museum Project

Recent films and the media storm around them prove that the horrors of slavery continue to loom in our collective consciousness. A chapter in our history, at least in its transatlantic form, we are glad to have closed. Or have we? What if we discovered that much of British life as we know it is built on capital given as compensation, not to the enslaved, but to those who owned them? A University College London project ‘The Legacies of British Slave Ownership’ headed by professor Catherine Hall, publicly funded by the research councils, seeks to uncover this lesser known set of stories for the public. A project that, she says, goes against the grain of our preoccupation with slavery’s ending: ‘There is deep amnesia: we only want to think about abolition’ – we long for a story where we were the ‘good guys’, or ‘Wilberfest’ as the anniversary of abolition has been coined.

‘It knocks people out; the scale of the compensation,’ reflects Catherine Hall, professor of Modern British Social and Cultural History at UCL, as we chat about her recent work leading this huge and systematic project that aims to reveal the legacy of slavery and slave-ownership on all aspects of British life at the time of abolition.

This far-reaching project is the most recent manifestation of her wider work of the last two decades that seeks to re-think the history of Britain through the prism of Empire – how Britain shaped its empire and was in turn shaped by it.

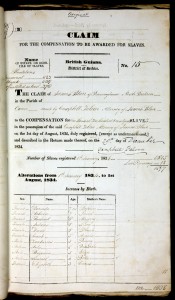

Original claim form for James Blair, awarded £83,530 in compensation for ownership of 1,508 people in British Guiana in August 1834. National Archives at Kew. (click to see the full size image)

When slavery was abolished, the British government paid out £20 million compensation to plantation and slave owners who, it was considered, would be adversely affected by the cessation of slave labour. That sum, Catherine points out to me is equivalent to the recent government bail-out of the banks: approximately 40% of state expenditure that year.

Applications for compensation came in from both British, American and Caribbean-based claimants, detailing their personal circumstances. Detailed records had to be kept, making it an incredible archive according to Catherine. I ask whether there have ever been barriers to access, recalling comments from another academic who has found it hard to access documents about the darker periods of colonial rule. No, Catherine explains, the state did not mind keeping records of these kinds of financial claims. No, the challenge has been the sheer task of painstakingly digitising approximately 47,000 claims.

There is open access to the project for the public who can search the claims by inputting data about a claimant’s name, occupation and address. See the project website: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs.

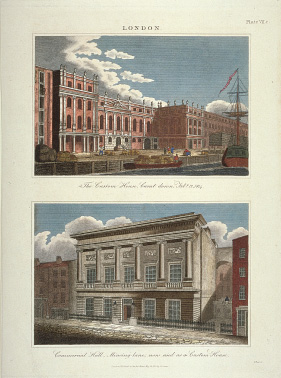

Portland Place, London, 1812. This street was a favourite abode for well-to-do slave-owners, including George Hay Dawkins Pennant (see below).

George Hay Dawkins Pennant (1764-1840) of Penrhyn Castle in North Wales and Portland Place in London, an absentee slave-owner who was awarded over £15,000 compensation for the freedom of 764 enslaved people in 1835.

Portland Place 2012 (from Google streetview). The buildings remain the same but are largely offices and embassies now

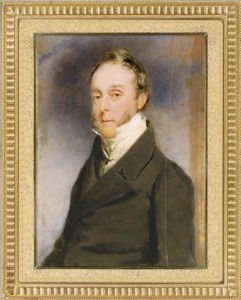

Portrait of George Hibbert (1757-1837) who lived on Clapham Common in close proximity to William Wilberforce and other prominent abolitionists. Hibbert was a merchant, slave and plantation owner. This portrait now features in the London, Sugar, Slavery exhibition at the Museum of London in Docklands. George Hibbert by Thomas Lawrence, oil on canvas, 1811. © Museum of London (click to see full size image)

Catherine’s main interest has been to uncover the scale of the compensation and to chart the impact of the compensation money on our social, political and cultural lives – the architectural impact, for example, to be seen in Gower Street just round the corner from where we meet. But the human impact is fascinating, too: Catherine tells me about a well known family of prominent slave owners and merchants based in Clapham, who mixed freely with the abolitionists at that time, even attending the same churches. There might have been rumblings in the House of Commons, but it did not seem to upset day-to-day lives.

Something that struck me was that over 40% of the claimants based in the Caribbean were women – owners of small plantations and ‘illegitimate’ daughters of slave owners. Similarly, in Britain there were many women claimants, primarily widows and single women whose financial stability depended on slave shares. I felt a twinge of disappointment with the sisterhood when this was revealed.

The project enjoyed a boost of public engagement after a slot on the Today programme, reaching 100,000 hits on the archive searching site. Most of these camefrom IP addresses in Britain and the Caribbean, fuelled by the current growth in family history research. Public engagement has similarly been increased by media coverage and partnerships with museums such as Hackney Museum and performances with theatres.

Curious, I asked if the project has sought to ‘out’ people whose families have been tied up with slave-ownership (prominent politicians, perhaps, coming to mind). Catherine said they had purposefully avoided this. The archive is there for people to use of their own accord.

Critical engagement with the project has come from a range of quarters: banks and insurance companies with slavery heritage, but also from those active in the movement for reparations, working for those with enslaved ancestors who would be able to claim compensation from the state. Catherine explains that the job of their project is to provide knowledge about the legacies of slave ownership as one aspect of this debate, for public use.

Portrait of Jane Bayne (1790-1865). Artist unknown. Jane was born in Jamaica and inherited ownership of 10 enslaved people there. She emigrated to Scotland in her late teens and married a doctor, living near Inverness until her death in 1865 aged 75. She was awarded £84 compensation for the ownership of 10 enslaved people in 1834. (click to see larger image)

Overall the project has proven that compensation capital affected many parts of Britain and has illustrated ‘how entangled our histories are’. There was a constant movement of people between Britain and the then West Indies, further refuting the mono-cultural myth of Britain: ‘the history of migration is not a separate history’ Catherine confirms as we conclude our conversation.

Leave a Reply