We all belong – portraits from Northern Ireland

Last year we were fortunate to contribute to a major exhibition, Adopting Britain, at the Southbank Centre, exploring 70 years of migration to the UK. Among the wonderfully varied projects featured in the exhibition, a set of photographs from Northern Ireland caught our eye. Beautifully composed against a simple dark backdrop, highlighting the diversity of people living in Belfast, the images and themes from the Belonging Project resonated strongly with us. We are delighted to feature some of the photographs from the project, which is a collaboration between the Migrant Centre NI and photographer Laurence Gibson. Laurence shares the idea behind the project below.

“I am a Vietnamese refugee. I was in this ship, which carried 295 passengers. The vessel maximum capacity was supposed to accommodate a hundred passengers only … the condition on the ship was horrific. There was no fresh water and a suffocating odour filled out the whole ship. Sometimes, when sea waves hit the ship, there was no shelter and we all got soaked.” Photograph of San Dinh © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

The Belonging Project came about when I was working with a journalist on a story on modern-day slavery. On contacting the Migrant Centre of Northern Ireland, I met with Jolena Flett. It became quickly apparent through our conversation that there was much more to migrants’ stories than abusive working conditions, although these are important to highlight. Jolene asked me to consider whether the story we were running represented anything ‘new’ to the public’s front page. The phrase that kept on coming up in conversation was “these people are human beings” – with the current crisis and migration from Syria, I think this is often forgotten.

After the meeting with Jolena I went away to think about how better to portray the lives of migrants coming to our country. Having grown up in Northern Ireland, I have seen an enormous change in the population, with new cultures coming in. It’s fantastic. I came up with the concept of the Belonging Project as a way of personalising the topic of migration, to remind the public that migrants are not a cohesive group aiming to invade the country and assimilate the population.“I had a good life in my home country,” “I cried for the first two weeks,” “I was heavily pregnant with no way of communicating to the doctors and nurses that surrounded me,” “When I am in Portugal, I miss Northern Ireland; when I am in Northern Ireland, I miss Portugal.” These reflections are vital to humanising the individuals who choose to move to our country.

All of our participants have experienced migration but in very different ways, with each having their own reason for moving to Northern Ireland. The common assumption in the UK that migration is a shift from a poor situation to a much-improved one is really quite presumptuous. We have recorded many stories of individuals who left happy lives with supportive friends, family, and jobs to move to uncertain situations. Why did they leave? In some cases, their partner or parents needed to move for study or work. Or perhaps their decision was shaped by the encouragement of friends who were already in Northern Ireland. Their reasons for moving are varied, from fleeing conflict to simply looking for a better life for their family. Let’s start treating these people as individuals and not numbers on a government statistics table. Just like those of us born here, migrants are not all good and not all bad. But before we batten down the hatches, let’s find out who they really are.

Public education is obviously paramount to our mission, but there are many seemingly smaller effects that aren’t so obvious. The simple act of allowing people to tell their stories and celebrate them in a public context is an enormous opportunity. From very humble beginnings of five portraits in a makeshift gallery space in the Migrant Centre offices, we have gone to a touring exhibition around Northern Ireland, and even to the Southbank Centre in London as part of their Adopting Britain exhibition. Libraries NI have provided a vital role in providing us with exhibition space in the community around Northern Ireland, having been the organisation to first discover us in our makeshift gallery almost two years ago. Currently, the Belonging Project is looking into the possibility of working in conjunction with a local boxing academy to show boxing as a cross-cultural unifier between migrant and non-migrant communities. I am so pleased to see the project continuing in a new and sustainable direction.

Laurence Gibson is currently based in London and specialises in partnering with a variety of charitable and commercial organisations to produce innovative still photographic series, often with audio accompaniments. http://laurencegibson.co.uk/

If you would like to see the Belonging Project in person, upcoming events include portrait exhibitions at the Belfast Waterstones bookstore from 25 February to 3 March and UNISON Northern Ireland from 1 to 11 March. More information on the project is available on their website: http://www.thebelongingproject.org/

“What helped me a lot was football: it basically helped me integrate into the local community because I was playing for local teams and getting to meet people. There’s no language barrier in football: everyone turns up and runs behind the ball and kicks it. There’s no, “You have to speak English”. It’s a great tool to break barriers.” Aruna, Guinea Bissau & Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“My mother used to read this, to me and my younger brother … this has very strong memories of my childhood, and when I felt happy and safe with my family. It’s important for me to pass it on, some of the information and storytelling, to friends and friends’ children – that is why I kept it all these years.” Cornelia, Greece/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

![“The object which I brought today is called mbira, it’s a Zimbabwean musical instrument which was made during the early 1880s. It’s a cultural musical instrument, played at cultural celebrations, gatherings, and also can be recorded with any genre of music. This object is important to me because it reminds me [of] back home and [because] it’s a true instrument of Zimbabwe, only made in Zimbabwe” –Everson, Zimbabwe](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/everson-zimbabwe.jpeg)

“The object which I brought today is called mbira; it’s a Zimbabwean musical instrument which was made during the early 1880s. It’s a cultural musical instrument, played at cultural celebrations, gatherings, and also can be recorded with any genre of music. This object is important to me because it reminds me [of] back home and [because] it’s a true instrument of Zimbabwe, only made in Zimbabwe.” Everson, Zimbabwe © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“So I came over to Broughshane up north. I just fell in love with the place. Just felt home. One of my children said, ‘Mommy, this feels like home.’ That was very touching because that was like a message to say – this is what your children want. You know, follow your dreams, follow your children’s dreams.” Maria, Angola & Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“I didn’t bring much with me when I left Portugal. I didn’t bring much. I put a tile in the suitcase I brought with me; I have it here, with the emblem of the city of Beja. I brought these tiles with the emblem of the city where I was born.” Luis, Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“I remember apartheid like yesterday; the thing that clings to me even why I think about it is the smells. The tear gas smells that always caught the back of your throat and the sounds of the sirens.” Nandi, South Africa/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

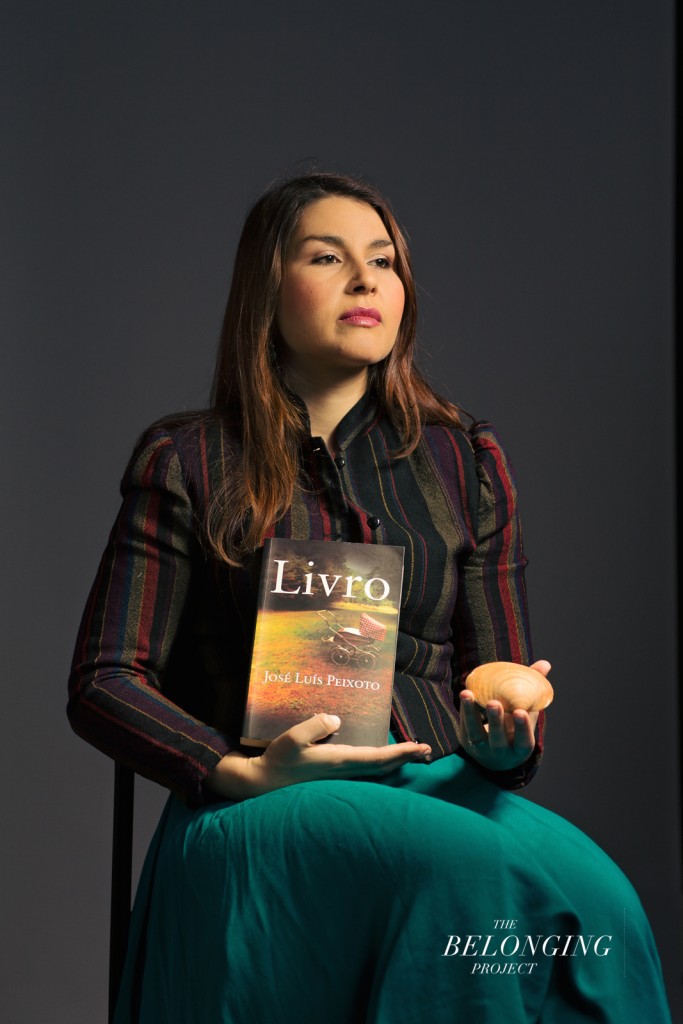

“I brought a book which is from one of my favorite writers in Portugal … it tells this story which is quite different from my own story, but nevertheless the feelings of a migrant person are the same, which is: you feel always split between two worlds and two countries, and if you’re there you want to be here, and if you’re here you want to be there. That’s very much in the book, and I relate to that.” Raquel, Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“As a migrant, I think every migrant would like to feel loved, accepted and appreciated in the country that they go to. And I too wanted to feel loved in the country that I came to, in Northern Ireland. And yes, I am different – my language is different, my colour is different, my values are different, my culture is different. But love me anyway.” Sangeetha, India/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

![[Why did you choose Ireland?] "I don’t know- maybe Ireland chose us" –Plamena, Bulgaria/Northern Ireland](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/plamena-bulgaria.jpeg)

Leave a Reply