“A keepsake is a very special thing”

In this Guest Blog, Sue McAlpine, freelance curator with the Migration Museum Project, gives us an insight into her Keepsakes experience.

When the Migration Museum Project asked me earlier this year to curate their Keepsakes exhibition – I had previously curated 100 Images of Migration at Hackney Museum in 2013, the first time that particular exhibition had been displayed – I jumped at the chance. I felt it chimed well with the work I had been doing at Hackney collecting people’s stories and objects. Everybody has a keepsake and a story to tell, I think, and I love hearing those stories – even more, I love giving people an opportunity to have their voices heard so that they can feel proud of their culture, share it with others and pass it on to their children. Keepsakes seemed a perfect way to do this.

Our guest blogger Sue McAlpine celebrating the launch of 100 Images of Migration at Hackney Museum in 2013. © Migration Museum Project

But collecting keepsakes turned out to be very different from collecting objects destined to end up in a museum, displayed for a time in a case and then wrapped in tissue paper and kept in an archival box in a museum store. The process of meeting the contributors, finding the keepsakes and hearing the stories seemed more personal and intimate. I liked the fact that these objects had a life of their own beyond being simply museum objects.

![2a Keepsakes contributors at Southbank Centre [Colour+Full]](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2a-Keepsakes-contributors-at-Southbank-Centre-Colour-Full1.jpg)

Keepsakes contributors share their keepsake stories at a celebration event at Southbank Centre on 2 May 2015. L–R Robert Winder (MMP Trustee and discussion chair), Maurice Nwokeji, Henning Wehn, Sajeela Kershi (honorary guest), Alishah Akram. © Migration Museum Project

What do we mean by the word ‘keepsake’? A keepsake is a very special thing that we keep to remind us of a person, or a place or a memory. It might have travelled with us in a suitcase from another country; we might have found it here; it might have been passed down through generations in the family. And, in a key difference from other museum objects, keepsakes are only loaned: once the exhibition they are part of is over, they are no longer part of the museum’s collection. The keepsakes that we have displayed at the Southbank Centre, for example, as part of the Adopting Britain exhibition in London’s Royal Festival Hall, will return to their owners once the exhibition is over, to continue their journey.

Keepsakes display in the Adopting Britain exhibition at Southbank Centre. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams.

I travelled to Peru in 1976 and bought a soft alpaca baby’s hat, which my son wore when he was born a year later. I still have it and, as part of our Keepsakes work with communities, took it to show a group of Latin American women in South London. Although it’s personal to me, it belongs to their culture. One of the Peruvian women, Celeste, quietly mended the holes in the hat, so now my keepsake has another chapter to its story. Who knows what its future might be? Perhaps keeping warm the tiny head of a future grandchild.

Celeste mends Sue’s Keepsake – a Peruvian hat her son wore as a baby. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Sue McAlpine.

Many migrants or refugees have suffered pain and loss: they may have escaped war or persecution in their own countries and, for many reasons, find it hard to put their story into words. It’s too raw. Many people don’t necessarily want to be identified by their story. But talking about a keepsake seems freer and easier.

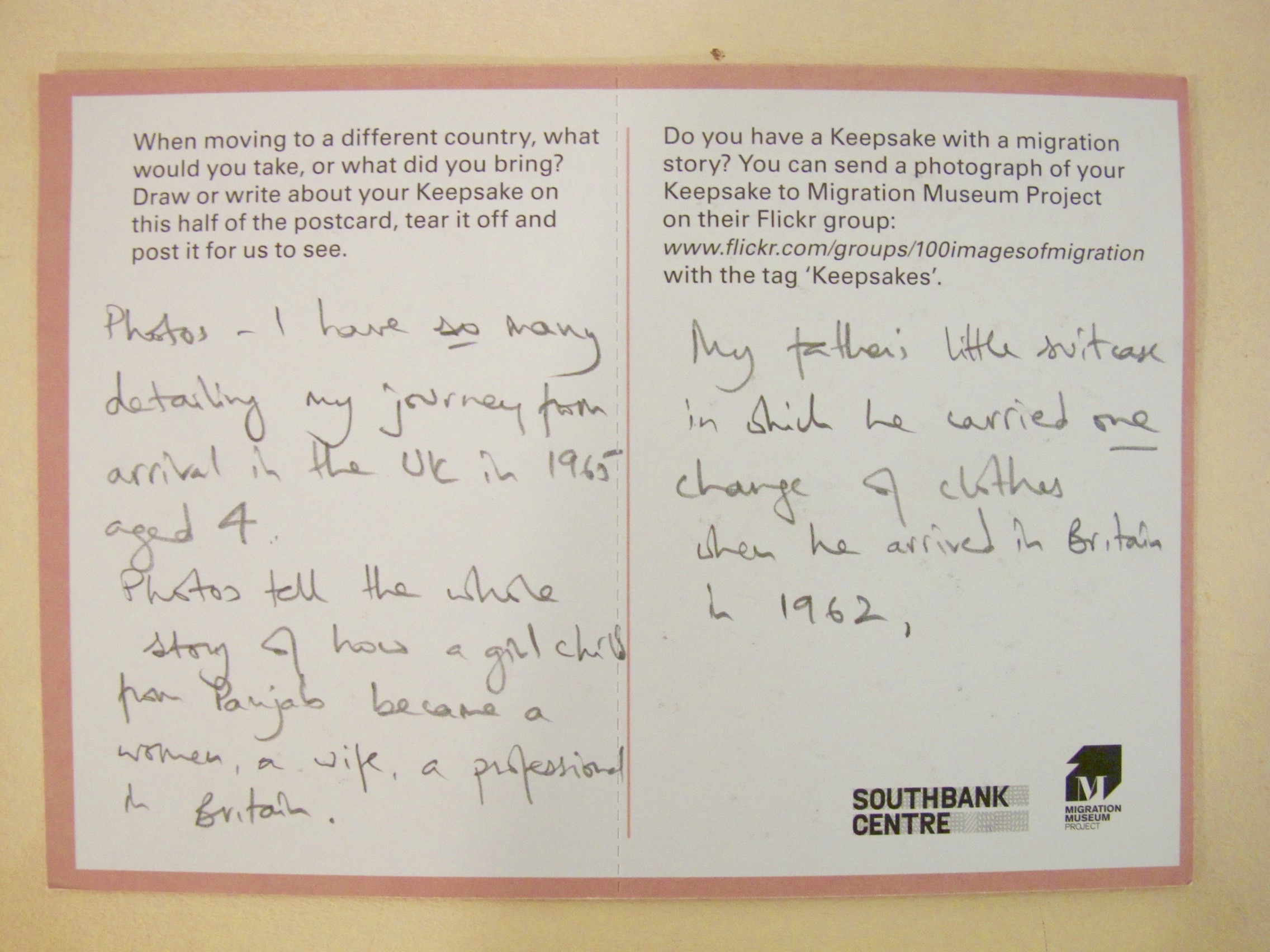

Keepsakes postcard – a visitor to Adopting Britain shares a little about her family keepsakes, just hinting at the depth of stories behind them. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams

I’ve known Maurice Nkoweji for some time. In 1970, he was a child in Nigeria, starving in the famine caused by the Biafran war. He and his younger brother – little boys who then knew only war and hunger – were rescued and came to this country with the Red Cross. I asked Maurice to contribute a keepsake for this exhibition and he gave me an Ekwe, a musical instrument made from a tree trunk (you can find out more about the Ekwe in Maurice’s description). He wanted to show something that reminded him of his Igbo culture and tradition in happier times. You can see a short clip of Maurice performing with his Afrobeat reggae band One Jah here, and you can watch Maurice talking about his Ekwe and arrival in Britain in this London Live TV clip.

Maurice’s Ekwe photographed by Keepsakes photographer Camilla before moving into its temporary home in the Adopting Britain Keepsakes display. © Camilla Greenwell

Anna Hegarty lent a tiny metal reindeer that comes from Lapland and travels with her everywhere she goes. In crowded cities it reminds Anna of the wide, open spaces of her own country.

Anna’s reindeer in its temporary home – the Keepsakes display in the Adopting Britain exhibition. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams.

Sasha Zavjalova’s Georgian metal plate with its stylised head of a young woman helps her to imagine the mysterious land where her grandparents grew up. During the Stalinist repressions, they were forced to leave their homeland and went to live in Soviet Estonia. When Sasha came to live in Britain seven years ago, the plate came with her, continuing its own migratory journey.

Sasha’s metal Georgian plate in the Adopting Britain Keepsakes display. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Poppy Williams

We want to continue this lovely project. We were able to show only a few keepsakes in the exhibition in London’s Southbank Centre, so we are now sharing more stories and more keepsakes with communities in South London. It’s an exciting project that’s living up to the initial high hopes I had for it. Every new engagement throws up new and exciting discoveries, so watch this space!

FULA (Latin American Elders) Keepsakes session. Marta brought in traditional Argentian maté gourd cups and silver straws which have been passed down from generation to generation in her family. © Migration Museum Project, photo by Sue McAlpine.

Sue McAlpine is currently freelancing as a curator, working especially in community engagement in museums. She joined Hackney Museum in 2006 curating exhibitions, managing collections and working closely with Hackney’s communities. Working backwards, before Hackney she worked in Notting Hill as a carnivalist, oral historian, exhibition designer and community historian; in 1990 she established an education service at Gunnersbury Park Museum and she was education officer at the Museum of London from 1977. Having curated the first showing of 100 Images of Migration at Hackney Museum, Sue has continued her involvement with the Migration Museum Project (of which she is a distinguished friend) and was the principal curator for the Keepsakes exhibition: a prototype of this exhibition is currently on view at the Southbank Centre, as part of the Adopting Britain exhibition.

Leave a Reply